A new breed of biotech

Lately I’ve been talking to a lot of biotech and pharma companies about their AI and data strategies. Enough that I’ve started to notice an emerging schism, or bifurcation, of companies into two broad philosophical camps.

The first camp (let’s call them ‘Class I’) are biotechs founded on top of a novel biological insight: the chance discovery of a family with an inherited pain disorder, or a group of elderly people with antibodies that protect them against neurodegeneration, or a bacterial protein that turns out to be useful for editing DNA. This has been the ‘standard’ sort of biotech company, historically.

Young Class I companies are rarely built to last. It’s taken for granted that drug development is so expensive, and prone to failure, that startups get one, maybe two, shots at success. Biotech companies are disposable rockets — run the experiment, build the rocket. If it takes off, great! If it crashes and burns, better to write off the loss and start anew.

The precarious existence of biotech companies (straddling life and death) is part of the reason why processes in the industry have been so artisanal and inefficient until now. It’s hard to justify spending investor capital on durable operational efficiencies in a paradigm where going to zero is by far the most likely outcome, success looks like a pre-launch acquisition by a top30 pharma, and launching multiple drugs independently is a pipe dream.

By contrast, the companies in the second camp (‘Class II’) seem to believe they have an opportunity to escape this inefficiency trap. These are the biotechs built around a core of computation, machine learning, and high-volume proprietary data generation.

The emergence of this second class is hardly new — the rising prominence of the computational biologist in academia has been commented on for at least a decade:

“Those who are able to make sense of the richness of data in the modern life sciences have now been put in the driver’s seat. As a result, computational biologists are now often principal investigators on grants, rather than co-investigators, and they are also last authors on groundbreaking publications.”

And because academia feeds the biotech industry, the impact extends to industry as well. Computational biologists are now taking up leadership positions, Aviv Regev’s appointment at Genentech being one of the more notable examples in recent years.

Increasingly, it is a computational rather than biological insight that instigates the founding of a biotech company. When Robert Buderi interviewed prominent biotech leaders based in and around Kendall Square1 for his recent book, many of them felt the coming decades would be defined by the melding of software and biology:

“When talking to people about new fields of growth that might power not just Kendall Square, but the entire region… Atop many people’s list is the convergence of artificial intelligence, healthcare, and biology.”

Computational insights tend to be more general than biological insights. Learn from enough data, and — the theory goes — you can uncover hidden structure that can be exploited to create many drugs. As an example of this thinking, take how Isomorphic Labs, the Google DeepMind biotech formed to apply AlphaFold to drug discovery, describes their philosophy:

“If we think of biology as fundamentally an information processing system — one that transmits information and maintains structure — we can start to see how it might share a basic underlying structure, or an ‘isomorphic mapping’, to information science.”

The promise of a computational data engine is that each turn of the crank (each learning cycle) generates data that feeds back into the platform and improves it for the future. The discovery engine becomes a compounding data asset that enables truly programmable medicines.

Even so, the market judges companies not by their platform, but by success in the clinic — which has so far not been forthcoming. It’s been hard to escape the fact that the industry as a whole still scales poorly with capital. As Aviv Regev framed the challenges in an interview:

“It’s been very difficult to move beyond an additive model: you put in more money and time, and you get something more out in the end. It’s a linear relationship. And that’s the best-case scenario, because sometimes you get less than you put in.”

Platform biotechs need to invest in their platform as well as advancing their drug assets into and through the clinic, so cash burn is elevated; the risk on their side is that they run out of cash before they’re had enough time and turns of the crank to learn how to reliably ‘get more than they put in’ (to borrow Aviv’s words).

Another challenge for Class II biotechs is that even if you have a nifty computational drug discovery platform, you are still often bottlenecked by the rest of the drug development process. It takes 1,000 (or more!) small steps to advance a drug through discovery, development, and past the regulators. As an executive I spoke with said: “If you automate 5 processes with AI, and do the remaining 995 the old way — you’re still pretty much a regular biotech”.

Broad discovery platforms give companies options, and while optionality is a resource it can also be challenging to manage. If it’s quick to generate 10, 100, or even 1,000 drug candidates the capital and work (indication selection, pipeline construction, trial design, vendor management, etc.) required to oversee and progress such a broad potential pipeline become binding constraints.

However, Class II companies are perhaps better incentivized to fix the scalability challenges up and down the stack than an ‘ordinary’ Class I biotech. If you have a scalable discovery engine, you need to think about scaling the rest of the operations too — the remaining “995 processes” — if you want to maximally benefit from the efficiencies of your platform.

Unlike traditional pharma and biotech companies, Class II biotechs are culturally technology companies at their core — led by technologists and staffed with software developers, data engineers, and machine learning experts. They have both the motivation and the means to invest in broad digitization.

For these companies, as they mature, it’s natural to ask: if software (broadly, automation) can make drug discovery more efficient, can it similarly make the entire drug development lifecycle more efficient? Serious engagement with this question at the leadership level is, for me, what distinguishes the second class of company from the first.

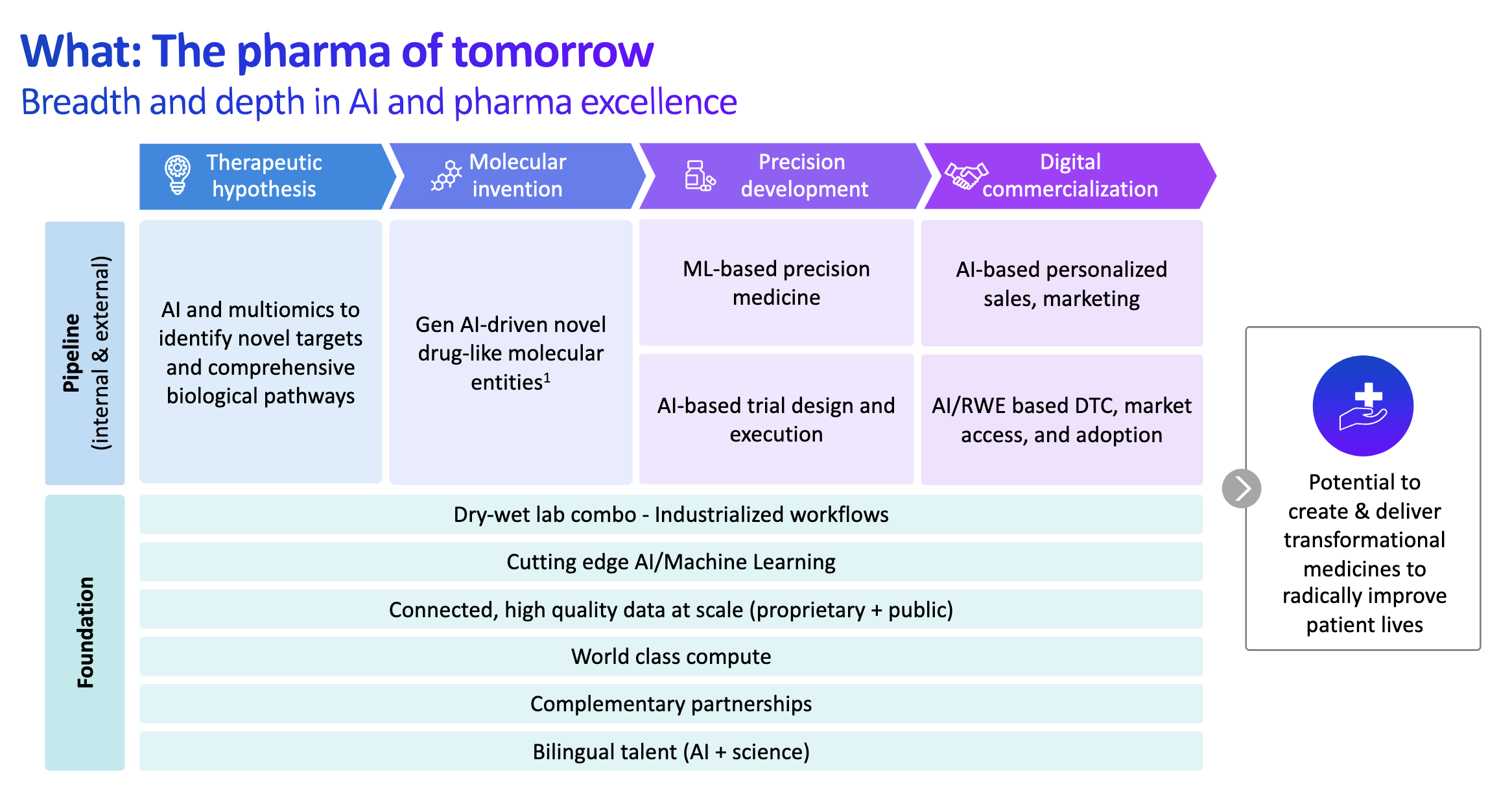

I think we’re starting to see investment in this in practice; many of the Class II companies I’ve talked to are starting to apply their computational biology team to projects beyond the core discovery platform, in the hope of unlocking efficiency throughout the organization. Companies like Recursion have publicly stated their ambition to automate (“industrialize”) the process across the stages of discovery, development, and beyond.

Formation Bio has similar automation ambitions:

“At Formation Bio, we are focused on scaling drug development with technology and AI, rather than with humans. Our technology platform integrates into all core aspects of the drug development lifecycle, providing meaningful insights that enable faster decision-making and operations.”

If things play out as these companies anticipate, legacy biopharma is facing an existential threat to their business model. In theory, software-first companies will eventually be able to act on new opportunities much cheaper and faster because they’ll have cut out so much of the operational overhead. Work that previously took 50 people, or 500, could be done with one (or even fully autonomously).

Unlike legacy biopharma, emerging companies can build up automation one layer at a time as they advance out of preclinical studies, into the clinic, and eventually to market. Incumbents have the additional burden of needing to first tear out all their old processes and start anew.

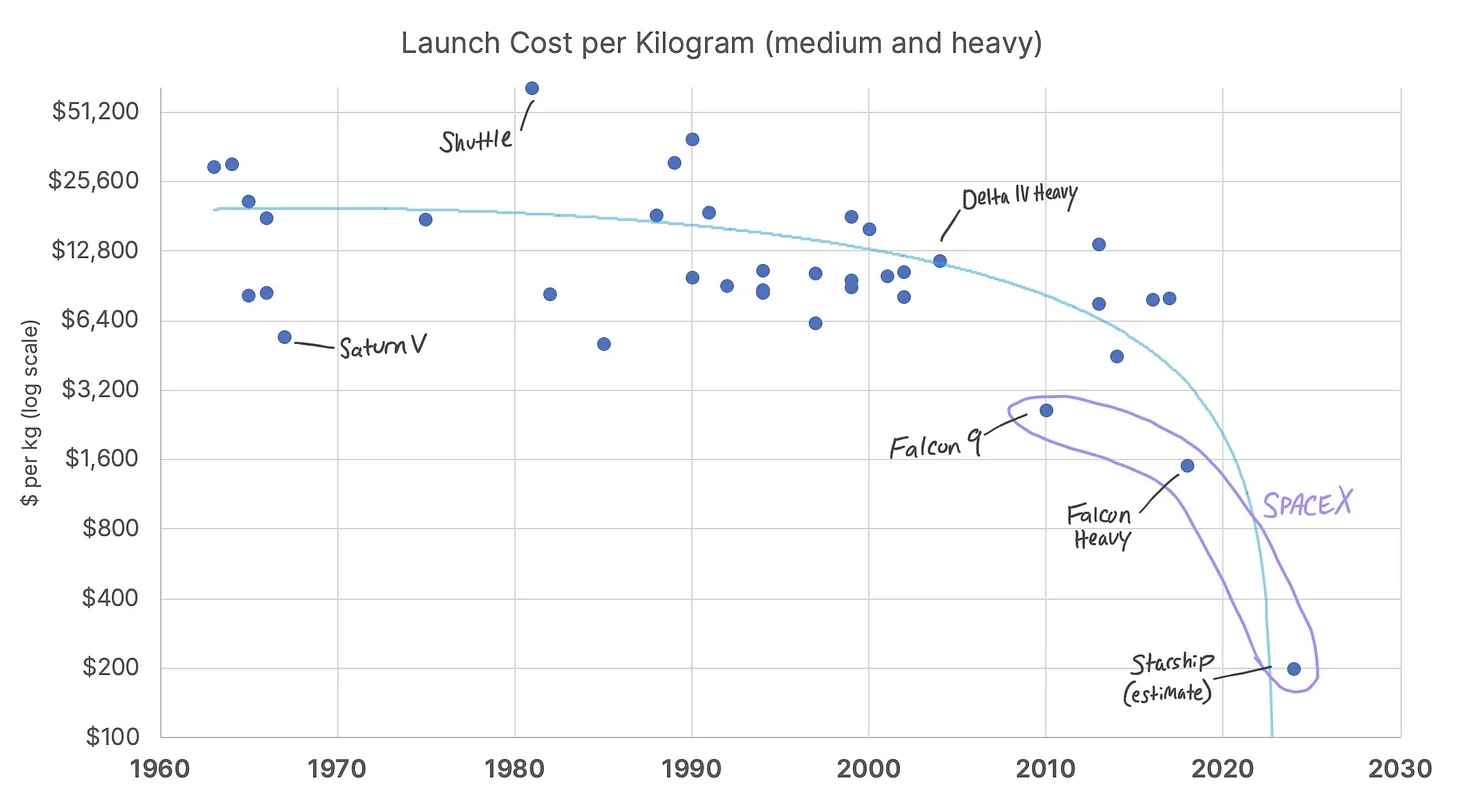

It seems possible we could be coming up on a SpaceX-like disruption for the industry: from the 1970s up to 2010, the average costs to launch rocket payloads into low earth orbit were stagnant in the range of $16,000/kg to ~$30,000/kg (see graph below). SpaceX brought launch costs down by 90% by vertically integrating design and manufacturing, simplifying components, and building boosters that return to earth for another launch instead of being scrapped. SpaceX’s next project, the fully reusable Starship, may bring costs down as low as $100/kg (another 90% reduction).

Most of the work required to bring a drug to market is knowledge work. But drug development is the knowledge work equivalent of a rocket launch, and like the space industry pre-SpaceX, there’s been little efficiency and reusability of common processes and components. The promise of artificial intelligence is that it enables the reusability and efficiency of software to extend beyond current bounds into work that requires human expertise today: clinical trial design, site selection and operations, competitive intelligence, sales and marketing, etc.

This is not to say that the established players are all sleeping on this. Some, like Sanofi, are making big investments in automation across their operations (including a partnership with Formation Bio and OpenAI):

“Our ambition is to become the first pharma company powered by artificial intelligence at scale, giving our people tools and technologies that focus on insights and allow them to make better everyday decisions.”

The question, then, is who will benefit most from the AI boom? The motivated and well-resourced incumbent? Or the software-native upstart without years of cultural and technical debt to overcome?

Perhaps none of this really matters, and the old truths will remain true: drug discovery is hard, the industry is built on top of painstaking (expensive) trial and error, and deep biological insights are ultimately what moves the needle. These new “techBio” companies have to yet to bring a drug to market, after all.

Or, perhaps, the barbarians are already at the gates.

-

Probably the most important square kilometre in biotech ↩