What is a good binding affinity for a drug?

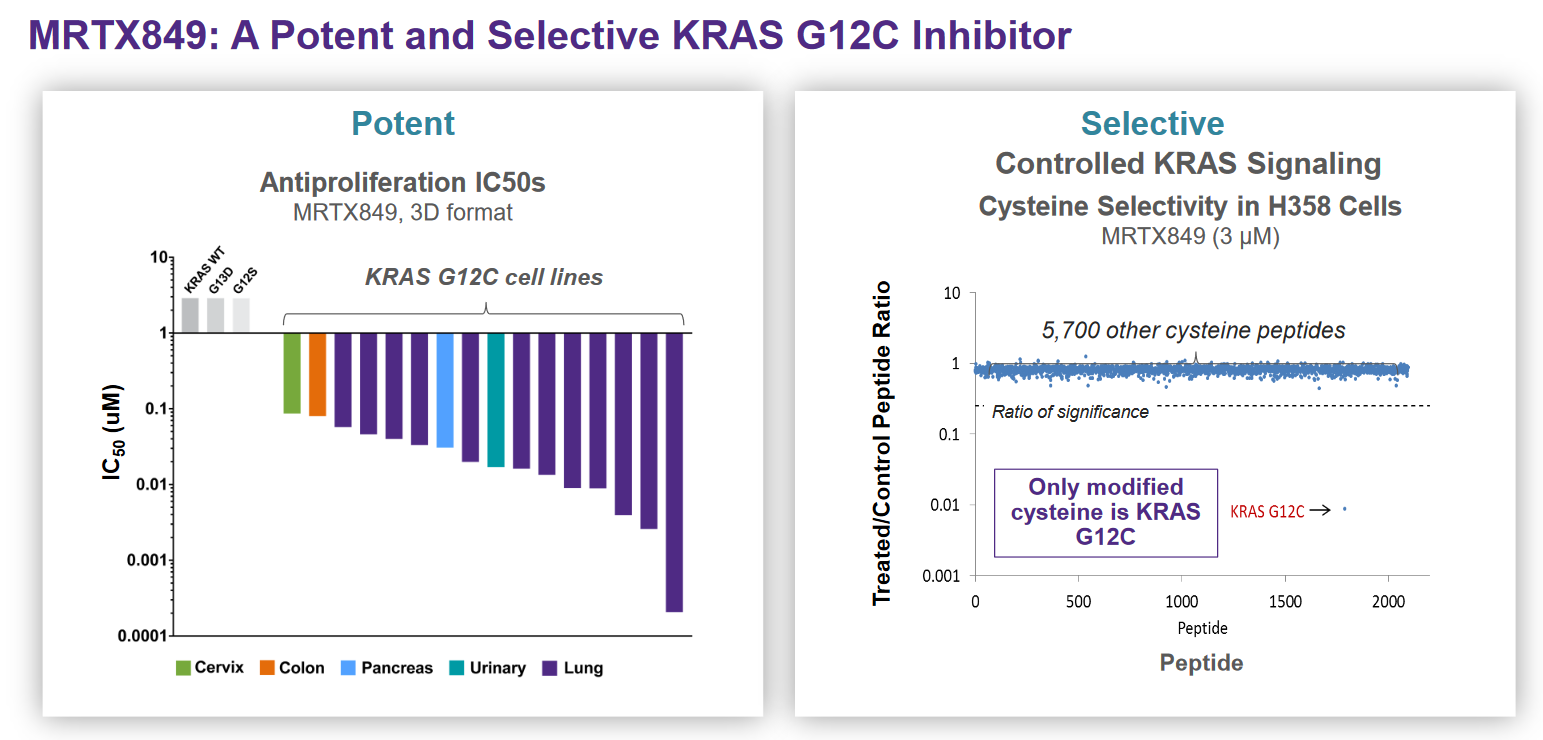

If you’ve spent any time looking at biotech company presentations you’ll likely have come across a slide like the below, from cancer drug developers Mirati, which nicely summarizes the activity, potency and selectivity of their KRAS inhibitor MRTX-8491.

The objective of this post is to review the concepts represented in the Mirati slide above (binding affinity and how it relates to potency and selectivity) and to provide some intuition as to what “good looks like” for these parameters. I’d also like to put together a reference for people without a strong background in pharmacology who nevertheless want to understand data presentations like this one.

For those who just want the quick summary: a binding affinity of less than 10nm (in terms of \(K_d\) / \(K_i\) / \(EC_{50}\) / \(IC_{50}\)) is generally considered “good”, but behind that value is a tricky balancing act that involves optimizing many other attributes of a drug like selectivity, solubility and molecular weight to ensure that patients are able to benefit from a drug that is effective, minimally toxic and without overly burdensome dosing requirements.

What is binding affinity?

Binding affinity is a measure of the strength of an interaction between a ligand molecule (i.e. a drug) and the target that it binds (often a protein; a receptor, enzyme, cytokine, etc.).

In the simplistic “lock and key” model, binding affinity reflects how well a drug “key” fits into its target “lock”. Intuitively, per the model, tight binding results from a close match of the “lock” and “key” shapes, as snug complexes are more energetically favourable than loosely bound ones. In reality, proteins and other large biological molecules are floppy and dynamic structures without rigid “locks”, but the analogy is useful regardless.

Generally, binding affinity is measured in terms of the dissociation constant (\(K_d\)) and is expressed in molar concentration. The dissociation constant is a measure of the ratio of unbound (dissociated) ligands to bound ligands at equilibrium. The lower the value of \(K_d\), the stronger the binding affinity. You may also see this ratio referred to as the inhibition constant (\(K_i\)) in the context of an inhibitory drug, which is essentially the same thing as the dissociation constant. For an overview of methods to measure \(K_d\), see the Wikipedia article on ligand binding assays.

An equation for a general reversible chemical reaction at equilibrium involving two molecules, \(A\) and \(B\), and a complex of the two, \(AB\) can be expressed as:

\[A_xB_y \rightleftharpoons xA + yB\]The dissociation constant is then calculated by measuring the concentrations of the various molecules at equilibrium and plugging the values into the below formula

\[K_d = \frac{[A]^x[B]^y}{[A_xB_y]}\]For our purposes, \(A\) could represent a drug, \(B\) its target receptor and \(AB\) the bound drug-receptor complex. The square brackets mean concentration. \(x\) and \(y\) represent the number of molecules of \(A\) and \(B\) involved in each instance of the reaction, respectively. The lower the \(K_d\), the more molecules of the drug (\(A\)) are bound to its target (\(B\)), and hence the tighter the binding. When measuring \(K_d\), it is important that the reaction be given sufficient time to properly equilibrate before measuring concentrations, or the \(K_d\) may be overestimated2.

When \(x = 1\) and \(y = 1\) (as is often the case in biology and pharmacology, e.g. when a single molecule of a drug binds a single receptor site), \(K_d\) is equal to the concentration of \(A\) at which \(A\) has bound half the molecules of \(B\) up into the \(AB\) complex at equilibrium (i.e. the concentration of \(B\) is equal to the concentration of \(AB\)). Per the below calculation:

If \(K_d = [A]\)

\[K_d = \frac{K_d[B]}{[AB]}\] \[1 = \frac{[B]}{[AB]}\] \[[AB] = [B]\]Another way of calculating \(K_d\) is by taking the ratio of the rate constant for the forward (binding) reaction (\(k_{on}\)) divided by the rate constant of the backwards (dissociation) reaction (\(k_{off}\)).

\[K_d = \frac{k_{on}}{k_{off}}\]However, the values of \(k_{on}\) and \(k_{off}\) are rarely determined in practice and you cannot draw firm conclusions about the duration of binding from \(K_d\) alone3. Although in general, a higher binding affinity will result in the drug spending a higher proportion time bound to the target than not.

The binding affinity is also related to the “fractional occupancy” of a drug i.e. the percent of a target bound by a drug, calculated with the following equation:

\[f_{occupancy} = \frac{[A]}{[A] + K_d}\]Fractional occupancy is useful because biological activity of a drug is often dependent on its ability to bind a large percent of available targets. From the equation, you can see that the \(K_d\) is particularly important at low concentrations of a drug (\([A]\)); a drug with a very low \(K_d\) can have high fractional occupancy even at low concentrations.

While binding affinity tells you how tightly a drug binds its target, it is not the same thing as biological “potency” or “activity”. These concepts are typically expressed using the following measures, which are more widely used in practice to screen drug compounds than \(K_d\) or \(K_i\):

- The half maximal inhibitory concentration (\(IC_{50}\)), which is the concentration of a drug at which the activity of its target (e.g. an enzyme) is reduced to 50% of its maximum activity. Drugs that inhibit the activity of their target are called “antagonists”

- The half maximal effective concentration (\(EC_{50}\)), which is the concentration of a drug that induces a response in its target that is 50% of the maximum possible response. Response being a measure of the biological activity of the target, such as the rate of an enzymatic reaction. Drugs that activate their targets are called “agonists”. Inverse agonists are drugs that cause an opposite biological response to what an agonist would cause.

While \(EC_{50}\) and \(IC_{50}\) are not formally measures of binding affinity, you may see them informally referred to as such - and it is true that a lower \(EC_{50}\) / \(IC_{50}\) implies a lower \(K_d\) / \(K_i\), all else being equal.

The values of the \(EC_{50}\) / \(IC_{50}\) are usually higher than the \(K_d\) / \(K_i\) values, but they can be the same under certain conditions (e.g. non-competitive binding). For mathematically inclined readers, this paper is a nice overview of how the \(K_i\) relates mathematically to the \(IC_{50}\) under various conditions.

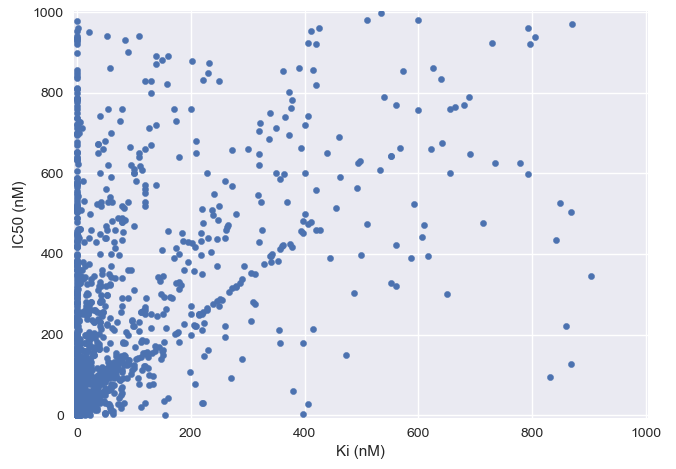

To roughly illustrate the relationship, I’ve plotted \(K_i\) vs. \(IC_{50}\) for a subset of small molecule drug-like compounds in BindingDB below - clearly there’s no simple linear conversion from one to the other:

Although the graph above has some examples of drugs with a higher \(K_i\) value than \(IC_{50}\), theoretically, the \(K_d\) / \(K_i\) values should not be lower than the \(EC_{50}\) / \(IC_{50}\) due to a mathematical relationship known as the Cheng-Prusoff relationship. However, in practice \(IC_{50}\) can sometimes be lower than \(K_i\) in the case of non-steady-state reactions4 or experimental error.

Why are \(EC_{50}\) / \(IC_{50}\) values generally larger than the binding affinity?

I previously mentioned that the values of the \(EC_{50}\) / \(IC_{50}\) are usually higher than the \(K_d\) / \(K_i\) values. So binding affinity is not the same as biological activity. This could be for a few potential reasons:

- In cases where a drug is competing for a binding site with other molecules (such as the natural ligand of a receptor) the values of \(EC_{50}\) / \(IC_{50}\) vary depending on the concentration of the other molecules. This is because an excess of the drug is required to outcompete other molecules for the binding site5

- The binding site may only become accessible under a rare or transient state of the target, and a high concentration of drug may be needed so there is enough drug “ready” to effectively bind and modulate the activity of the target in the brief periods when it is possible to do so5

- Not all binding is converted into biological activity

That last point is worth expanding on, while full agonists maximally activate their target, partial agonists only elicit a sub-maximal response, regardless of their concentration. Below is a nice simple graph from Wikipedia’s article on ligands that well illustrates this concept.

Partial agonists can be desirable in instances where maximal activation of the target is associated with toxicity or would lead to receptor desensitization6.

Inhibitors either directly bind to the active sites of their targets and block the binding of the natural ligands (competitive inhibition) or bind elsewhere on the target and inhibit activity indirectly through inducing a change in the conformation of the target or stabilizing a particular conformation (allosteric or non-competitive inhibition). Allosteric or non-competitive inhibitors may exhibit partial inhibition despite a high binding affinity, by reducing the effectiveness of their target without eliminating activity entirely.

What target affinity do drug developers aim for?

When embarking on a drug discovery program, companies will screen libraries of compounds7 using a particular assay and measure binding affinity/potency for each, progressing the highest potency “hits” for further development. The assays to measure potency have a variety of potential designs, depending on the biological function of the target. In the Mirati example at the beginning of this post, they measured activity (\(IC_{50}\)) by determining the level of MRTX-849 required to half-maximally inhibit the proliferation of cancer cell lines carrying the target mutation (KRAS G12C).

As a general heuristic, small molecule drug developers want to achieve an affinity of less than 10nM for their drugs. The specific cut-off is somewhat arbitrary, but the range below 10nM \(K_d\) / \(K_i\) / \(EC_{50}\) / \(IC_{50}\) is historically where many effective drug compounds have ended up and is low enough to for drug developers to be confident that they are sufficiently engaging the desired target. To quote Derek Lowe:8

The lower [the \(IC_{50}\)], the better, other things being equal. Most drugs are down in the nanomolar range – below that are the ulta-potent picomolar and femtomolar ranges, where few compounds venture. And above that, once you get up to 1000 nanomolar, is micromolar, and then 1000 micromolar is one millimolar. By traditional med-chem standards:

- Single-digit nanomolar = good

- Double-digit nanomolar = not bad

- Triple-digit nanomolar or low micromolar = starting point to make something better

- High micromolar = ignore

- Millimolar = can do better with stuff off the bottom of your shoe

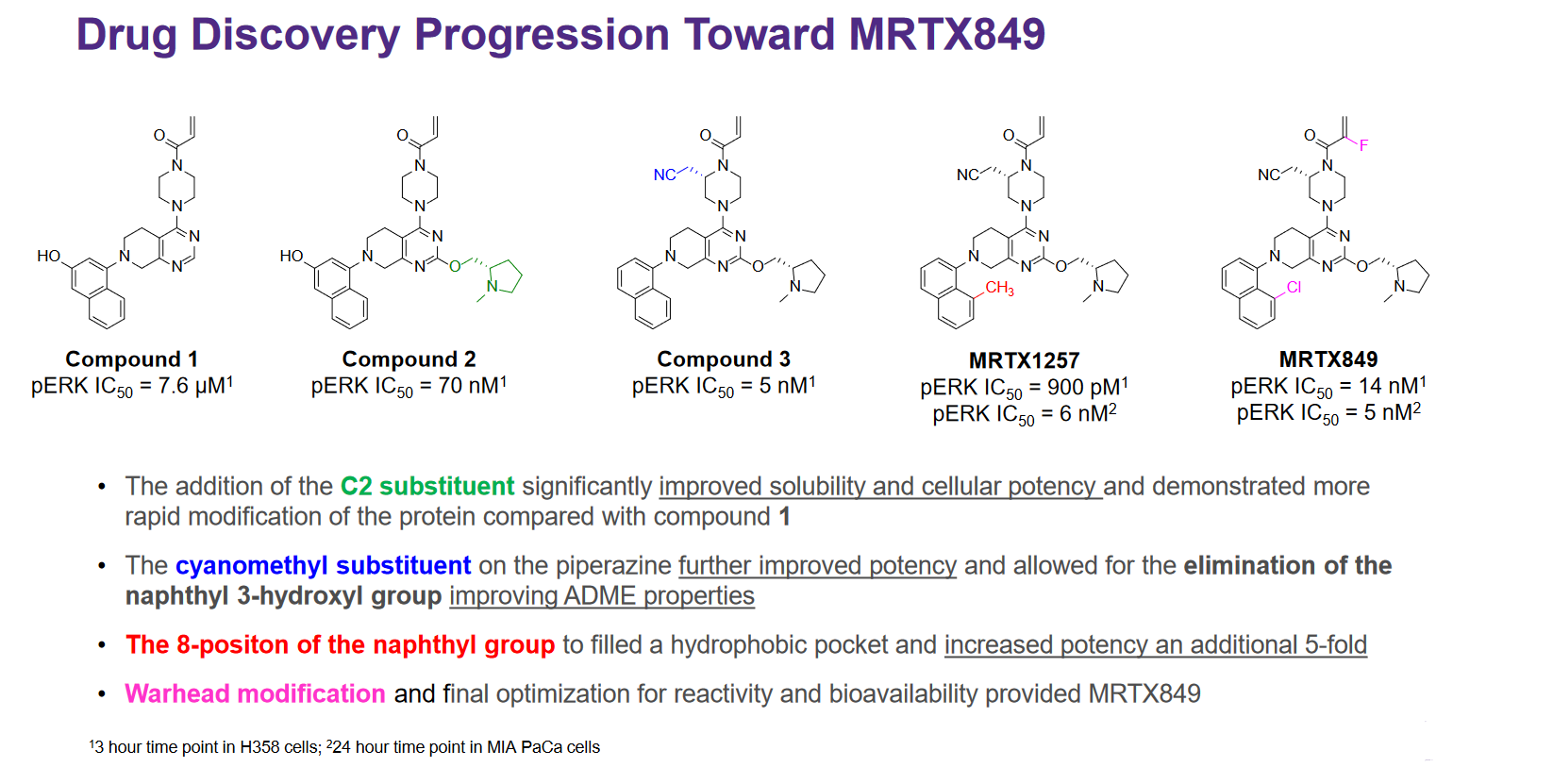

This is nicely demonstrated by the below slide from Mirati’s presentation at AACR in October 20199, where they outline the modifications made to their starter compound to increase potency and get to their eventual lead compound, MRTX849:

However, compared to small molecules, so-called “biologic” therapeutic modalities can have extremely strong binding affinities at the upper end of what is feasible with small molecules - a feature that has helped make this class of drugs so effective and generally safe. For example:

- Monoclonal antibodies typically have binding affinities in the low picomolar range, with a reported median around 70pM10. For example, the megablockbuster anti-TNF monoclonal antibody Humira has a measured \(K_d\) at 8.6pM11

- Cas9+sgRNA \(K_d\) for a perfectly matched target is ~1nM12, but varies significantly for off-target sequences13

- By design, antisense oligonucleotides are complementary matches to their target sequences and can exhibit picomolar (\(10^{-12}\)) \(K_d\) values14

So while 10nM may be sufficient for a small molecule, antibody drug developers may expect a bit more from their lead candidates before progressing it into clinical development.

What other related metrics are potentially important apart from affinity, activity and potency?

Going from initial hit to a final drug often involves making trade-offs in the various attributes of a molecule; optimizing for binding affinity over all else could result in an overall sub-optimal drug. To quote an article by J. Singh:15

A major challenge in drug discovery is achieving high potency and selectivity in a compound without increasing its molecular mass to the point at which beneficial pharmaceutical properties are jeopardized

I’ve picked a few additional metrics to cover in this post; selectivity, ligand efficiency and covalent binding.

Selectivity:

Selectivity, the propensity of a drug to bind one target over another, is a critical attribute of a drug to manage. Drugs that are “highly selective” have a high binding affinity to the primary target, and low binding affinity with undesirable target, and this is what Mirati is illustrating on the right hand side of their slide at the beginning of the post. It may be desirable for compounds to bind multiple targets if there are multiple pathways that contribute to a disease. Many approved drugs bind multiple related proteins, such as the JAK inhibitors and other pan-kinase inhibitors.

Cranking up the binding affinity for the primary target as high as possible may also increase its propensity to bind “off-target”, resulting in toxicity. As such, there can be a sort of “Goldilocks zone” for binding affinity that is influenced by the biological context in which the drug is intended to be used. A key way in which drug developers will test their drug candidate is by counterscreening against a library of targets associated with toxicity e.g. hERG (“antitargets”) to check that their drug does not bind too well to these “antitargets”.

Ligand efficiency:

Another metric drug developers are likely to look at is ligand efficiency, a measure of the binding affinity achieved for the molecular weight of the compound. Lower molecular weights are generally preferable, as bigger drugs are less soluble and harder to get into the target cells. Lipinski’s famous “Rule of five” heuristic calls for a molecular weight of less that 500 daltons, although lately more and more big oral drugs have come to market - oral semaglutide being a particularly good example.

Covalent binding

Most drugs bind reversibly to their target. MRTX-849 is actually a targeted covalent inhibitor, meaning that it forms (potentially irreversible) chemical bonds with its target. Drug developers were historically reluctant to pursue covalent drugs systematically due to concerns over toxicity and off-target reactivity, but there has been something of a resurgence lately spurred by the success of drugs like ibrutinib. To quote J. Singh again:15

Inhibitors that rely on covalent bonding dramatically favour the bound form, which leads to potencies and ligand efficiencies that are either exceptionally high or, for irreversible covalent interactions, even essentially infinite. Covalent bonding thus allows high potency to be routinely achieved in compounds of low molecular mass, along with all the beneficial pharmaceutical properties that are associated with small size

Calculation of affinity for covalent inhibitors is approached differently that for non-covalent inhibitors, as the reactions are not reversible. The \(IC_{50}\) is theoretically of limited value because of the influence of reaction time on the value - however, Mirati has still chosen to report it.

Other considerations:

When designing a drug that will bind competitively it is also important to consider the relative affinity of the natural ligand for the target versus the drug’s, as strongly binding natural ligands will be harder to displace and may require especially high binding affinities.

Other factors that may be important include the shape and steepness of the dose-response curve (related to width of the therapeutic window), cell to cell variability within a screening assay sample16, reaction kinetics and ligand binding thermodynamics17.

-

Mirati June 2019 corporate presentation ↩

-

https://elifesciences.org/articles/57264 \(Kd\) values may have errors in the literature. Many studies do not control for titration or demonstrate equilibrium ↩

-

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21638733/ ↩

-

An example of a non-steady-state reaction is one involving a covalent (non-reversible) inhibitor (such as ibrutinib), where the \(IC_{50}\) would decrease over the course of an experiment as the inhibitor depletes the pool of potential targets. In general, time has a significant influence on \(K_d\) / \(K_i\) / \(EC_{50}\) / \(IC_{50}\) values because measures of binding affinity assume equilibrium. Measurements that are taken “too early” have the potential to overestimate the values, because the system may not have reached equilibrium yet, see this paper for further details. ↩

-

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8869127/ ↩

-

For a high level overview of drug screening methods compared to the “screening” performed by the immune system, I recommend this post by Derek Lowe: https://blogs.sciencemag.org/pipeline/archives/2021/02/01/screening-within-and-without ↩

-

https://blogs.sciencemag.org/pipeline/archives/2008/03/27/start_small_start_right ↩

-

https://www.mirati.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/AACR-NCI-EORTC-Clinical-Data-Presentation_Janne_October-2019-2.pdf ↩

-

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25536073/ ↩

-

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19188093/ ↩

-

https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.09.09.290668v1 ↩

-

https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/176255v3.full ↩

-

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11751323/ ↩

-

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24013279/ ↩

-

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28276703/ ↩