Where are the other Luxturna's? Challenges with gene therapy for inherited retinal diseases

Luxturna, approved in December 2017 in the US1 and November 2018 in the EU2, is a landmark in the history of gene therapy and a transformative3 treatment for patients with inherited retinal disease (IRD) caused by biallelic RPE65 mutations.

Luxturna’s approval kicked off a period of gene therapy optimism; there seemed to be an expectation at the time that a wave of gene therapies would soon follow, with a 2017 MIT report predicting 39 US gene therapy approvals by 20224 and the FDA saying in 2019 that they expected to be approving 10 to 20 cell and gene therapies a year by 20255. In the months following Luxturna’s approval the FDA issued statements and guidance supporting fast-track regulatory processes6, suggesting that gene therapies could qualify for the regenerative medicine advanced therapy (RMAT) designation.

Big pharma also started to buy into IRD gene therapies at the time, with back to back acquisitions in early 2019 of Spark by Roche for $4.8bn7 and Nightstar by Biogen for $800m8 (although the value of the Spark deal was principally driven by the haemophilia program). Janssen and Meiragtx also announced their $100m partnership in January 20199.

In theory, gene therapy has many advantages for the treatment of IRDs:

- There is significant unmet need; most IRDs have few or no effective treatment options

- The causal genes for many inherited retinal disorders have been identified and are well-understood10

- The eye is immune-privileged, which limits the potential for the immune side effects that have historically presented a major problem for gene therapy programs11

- Cells in the retina are generally post-mitotic (not actively dividing), allowing for sustained gene expression without the need for genomic integration of the transgene, with transgenes preserved over time11. This is in contrast to liver-directed programs like in haemophilia where transgene expression has faded over time12

- The eye is a small and enclosed organ, and hence local delivery is possible with relatively low doses of vector genomes compared to the amount required for systemic or liver delivery. This keeps manufacturing costs and side effect risk down11

- Being on the surface of the body, the eye can be directly visualized and accessed for local administration11

- Gene therapy can be administered to a single eye, and so patients can act as their own control groups in clinical trials which reduces enrolment size (at least in theory, we’ll come back to this)

Yet, nearly five years on from Luxturna’s first market authorization, and in spite of a rich pipeline of ophthalmology gene therapies, there have been no further approvals for ophthalmologic gene therapies and only a handful of approvals for gene therapies in other indications. Why is this the case? And when we see another Luxturna?

Luxturna had only modest commercial success

Despite Luxturna’s laudable technical, clinical and regulatory successes, Spark’s commercial rewards for developing the gene therapy were minimal - in large part because there are so few addressable patients. Quarterly US sales hovered around $10m prior to Roche’s acquisition, even with its high US list price at launch of $425,000 per eye.

Table 1: Luxturna US revenue by quarter

| Time period | US sales |

|---|---|

| Q1 2018 | $2.4m |

| Q2 2018 | $4.3m |

| Q3 2018 | $8.9m |

| Q4 2018 | $11.4m |

| Q1 2019 | $9.8m |

| Q2 2019 | $11.5m |

| Q3 2019 | $6.9m |

| Total | $55.2m |

Source: Spark’s SEC filings

Spark was able to supplement their US revenue stream by licensing out Luxturna’s ex-US rights to Novartis for $105m upfront and $65m in milestones (plus royalties)13, as well as selling their paediatric priority review voucher to Jazz pharmaceuticals for $110m14. Although when taken as a whole Spark only made around $300m from Luxturna up until their acquisition, which hardly recoups the $568m in expenses they incurred from IPO up to Luxturna’s launch.

Table 2: Spark’s annual R&D costs and total operating expenses from IPO up to the Luxturna’s launch (note that this also includes expenses related to their haemophilia program, among others)

| Time period | R&D costs | Total operating expenses |

|---|---|---|

| FY2013 | $54.9m | $57.3m |

| FY2014 | $17.1m | $25.0m |

| FY2015 | $46.0m | $69.4m |

| FY2016 | $97.5m | $145.6m |

| FY2017 | $143.8m | $270.6m |

| Total | $359.3 | $567.9m |

Source: Spark’s SEC filings

Following the acquisition public sales figures are not available as neither Roche nor Novartis breaks them out. It seems safe to assume that Luxturna is not generating meaningful revenues for either company. I suspect that the limited return on investment from Luxturna has been a factor deterring other companies from pursuing gene therapy programs for other IRDs.

The troubled clinical stage pipeline of IRD gene therapies

Outside of Spark, the situation is not hugely encouraging, with public ophthalmology gene therapy companies faring poorly relative to the broader biotech indices. The chart below shows the stock performance of listed ophthalmology gene therapy biotechs with programs in clinical stage since 2017 (including those with programs in IRDs and acquired diseases such as age-related macular degeneration). Outside of a few brief spells of outperformance relative to the XBI the cohort has not performed well on average (“AVG” line) and has quite substantially underperformed the XBI since mid-2020.

The active clinical ophthalmology pipeline is now somewhat sparse and early-stage. As of the time of this post, Fightingblindness lists only 17 gene therapy programs targeting specific genetic mutations causal for IRDs on their tracker, split between achromatopsia, choroideremia, Leber congenital amaurosis (LCA), retinitis pigmentosa (RP), and juvenile retinoschisis, and mainly in phase I or II.

Unfortunately, a significant contributing factor to the current immaturity of the clinical stage IRD pipeline has been the recent failure of a number of late-stage programs in pivotal trials. To name some specific examples:

- GenSight’s Lumevoq (lenadogene nolparvovec) for Leber hereditary optic neuropathy (LHON) - announced April 201815

- Biogen/Nightstar’s BIIB112 (cotoretigene toliparvovec) in X-linked retinitis pigmentosa (XLRP) - announced May 202116

- Biogen/Nightstar’s BIIB111 (timrepigene emparvovec) in choroideremia - announced June 202117

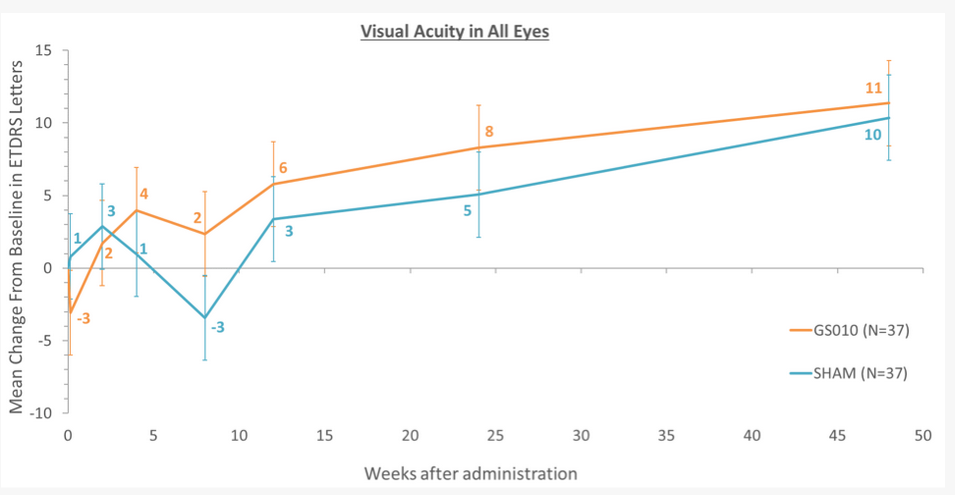

GenSight’s failure in particular is an interesting case because they used a design in which one eye was treated and the other untreated, and attributed the failure on the primary endpoint to an “Unexpected improvement in the untreated eye”, as shown in their graph below15. The theoretical benefit of using patients as their own controls may not be a benefit after all, as gene therapies seem in some cases to spread to the contralateral (non-injected) eye.

Source: GenSight press release15

In theory, Lumevoq is still the next closest IRD gene therapy to market as it was submitted to regulators in 2020 despite the failure18 (and it is technically already sold in France under an early access program19). However, GenSight were rebuffed by the FDA who asked for an additional placebo controlled trial, and the EMA regulatory process is delayed due to manufacturing challenges19 - so their future prospects of approvals seem low, at least in the short term.

After GenSight, MeiraGtx/Janssen have the next most advanced program with a phase III in XLRP which is supposedly reading out in later in 2022, and which will hopefully succeed where BIIB112 failed. Apart from that there’s not much that seems particularly close to an approval, and a number of phase II programs were previously in the pipeline no longer seem to be actively developed, some examples of which I have compiled in a (non-exhaustive) list below:17

- Roche/Spark’s SPK-7001 for choroideremia

- AGTC’s rAAV2-CB-hRPE65 for RPE65mut LCA

- AGTC’s program for X-linked retinoschisis

- Abbvie/RetroSense’s gene therapy for ChR2 in RP

- Coave/Horama’s gene therapy for RPE65 mutations in RP

- Oxford BioMedica/Sanofi SAR422459 for Stargardt disease

- Oxford BioMedica/Sanofi UshStat for Usher syndrome

Big pharma’s enthusiasm for IRD gene therapies also appears to be on the wane - Roche pulling out of their collaboration with 4D molecular therapeutics for 4D-110 in choroideremia20 being a recent example.

So why has it been so challenging for IRD gene therapies to live up to their promise?

The challenges with gene therapy for IRDs

I think the key challenges with development and commercialization of gene therapies for IRDs fall mainly in to the following 5 categories, which I’ll cover in more detail below:

- Epidemiology (too few addressable patients per mutation)

- Efficacy is hard to demonstrate

- Complex manufacturing

- Treatment and administration related safety risks

- Limited AAV packaging capacity

Epidemiology (too few addressable patients per mutation)

IRDs are rare and genetically fragmented with over 28021 causal genes identified, resulting in tiny addressable patient populations for any gene therapy targeting a specific mutation. In general, the more severe the symptoms, the more rare the condition. For example, take the IRDs for which gene therapies are under active development and their prevalence in the table below.

Table 3: Prevalence of IRDs targeted by gene therapy programs

| IRD | Prevalence | Approximate prevalent patient number - US, EU, UK and JP |

|---|---|---|

| Retinitis pigmentosa (RP) | ~1:4,000 | ~243,000 |

| Juvenile retinoschisis | ~1:15,000 males | ~32,300 |

| Achromatopsia | ~1:40,000 | ~24,300 |

| Leber congenital amaurosis (LCA) | ~1:50,000 | ~19,400 |

| Leber hereditary optic neuropathy (LHON) | ~1:50,000 | ~19,400 |

| Choroideremia | ~1:75,000 | ~12,900 |

Source: Orphanet

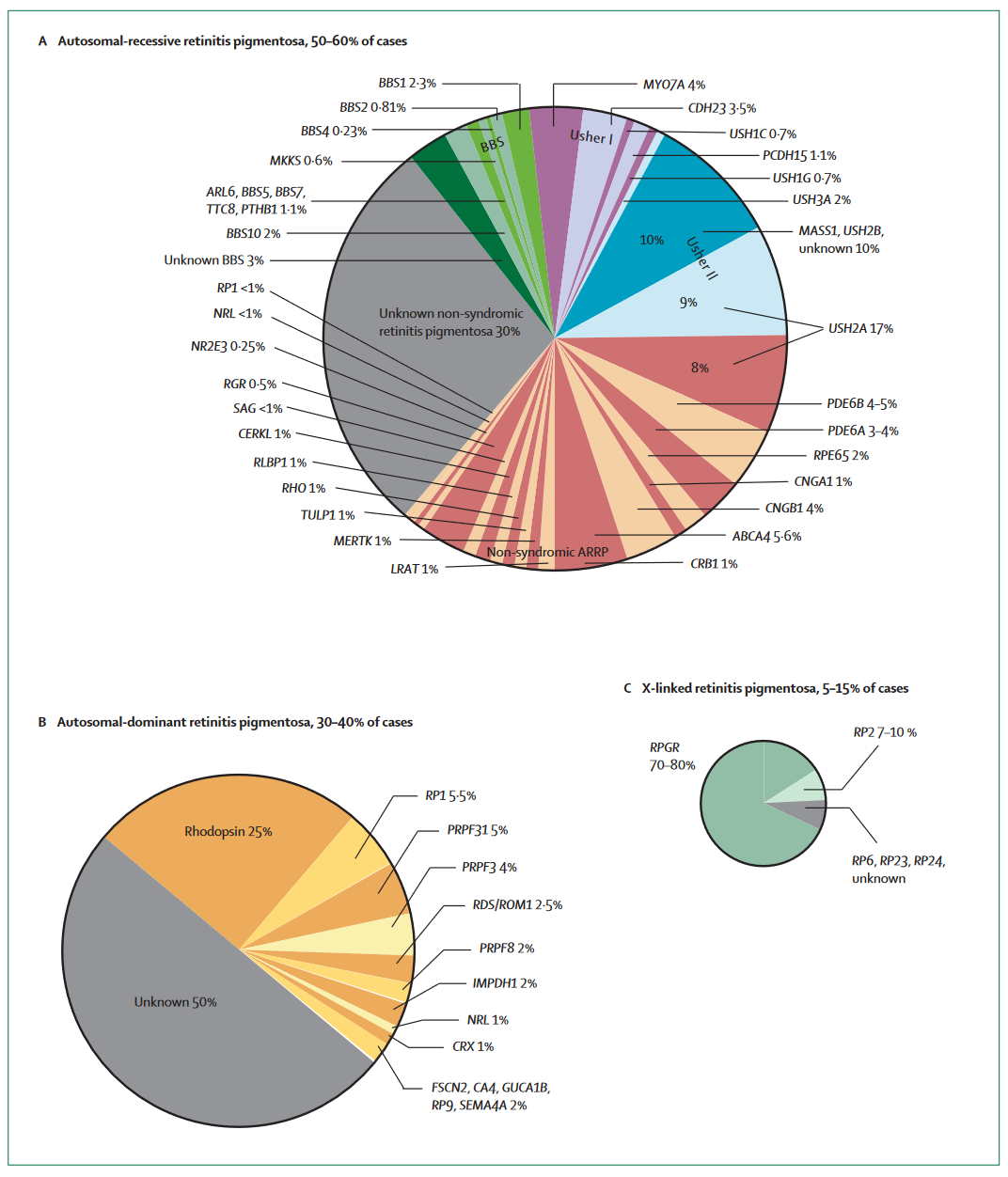

These conditions are rare to start with, and each of these conditions are in turn caused by mutations in many different genes. The RPE65 mutations that Luxturna addresses are only responsible for ~10% of LCA and ~2% of RP, for example. The below graphic from a Lancet review of RP22 makes it clear just how fragmented these indications are.

With a specific gene therapy program only able to address one mutation (typically), this genetic fragmentation is a major limiting factor for the commercial opportunity of gene therapy programs; Gene therapies are trying to address sub-slices of slices of an already small pie. This dynamic is not unique to RP, many IRDs have similarly fragmented genetics.

The low number of patients per indication-causal mutation pair affects the viability of gene therapies in several ways:

- Poor recruitment feasibility. This has manifested in long recruitment times for clinical trials, with many being open for years. A pertinent example is AGTC’s phase I/II CNGB3 achromatopsia trial, first posted in November 2015 and still listed as recruiting

- Low commercial viability and sales, despite extremely high prices

- Poorly characterized natural history of many IRDs23, which can lead to difficulties fulfilling regulatory requirements and in the proper design of clinical trials

Efficacy is hard to demonstrate

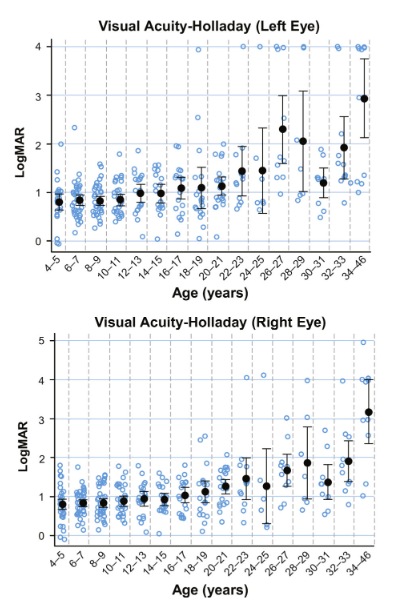

Most IRDs progress slowly over decades, with significant visual loss only becoming apparent in adulthood. The most severe IRDs with childhood onset of blindness tend to be very rare, and the more common IRDs tend to be less severe and progress slowly. As an example, the natural history of visual acuity in patients with biallelic RPE65 mutations is shown in the graphs below24, with little change evident between the ages of 4 and 20.

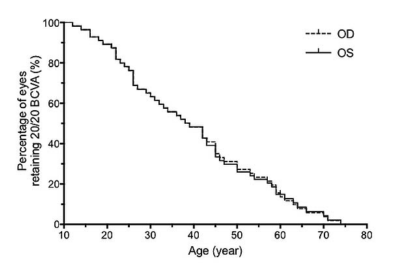

As another example, the slow but steady progression of choroideremia over many years is represented in the graph below25.

Slow disease progression naturally means that long (multi-year) trials will be required to demonstrate clear separation between intervention and placebo arms, even if the gene therapy is highly effective.

Most IRDs cause the degeneration of rods and cones in the retina which cannot be recovered once lost. While the degeneration often begins early in life the loss of visual acuity is often not apparent to the patient until much later on. This dynamic means that intervention with gene therapy is theoretically most beneficial if done as early as possible, before the onset of obvious symptoms. In some cases restoration of the visual cycle with gene therapy can improve vision rapidly (e.g., in LCA), but for most IRDs there is likely a limited window for meaningful intervention. Taken together with the slow rates of progression, patients with IRDs may need to be given a gene therapy in early childhood and be followed for decades for any kind of dramatic efficacy to become apparent. When compared to other conditions amenable to gene therapy such as spinal muscular atrophy (a fast progressing disease) and haemophilia (a highly reversible disease), the relative challenges with efficacy demonstration in IRDs are clear.

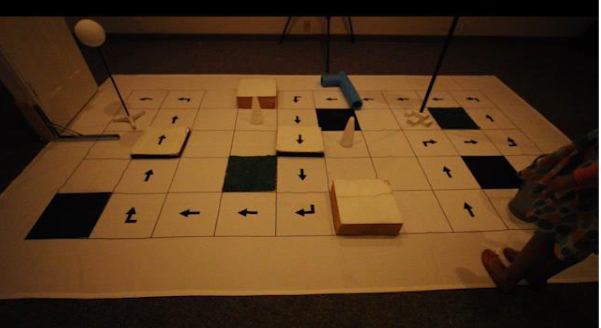

Briefly, yet another confounding factor is that the measurement of visual acuity is partly subjective, and variable patient effort can bias the trial results23. The primary endpoint for Luxturna’s phase III even had patients complete an obstacle course in low-light conditions26, a far cry from the objective endpoints standard in oncology and other therapy areas.

Complex manufacturing

Gene therapy manufacturing is complicated, costly, and inefficient. Much has been made of the cost of gene therapy manufacturing; systemically dosed programs (often \(1 \cdot 10^{15}\) vector genomes or higher) can cost as much as $100,000 per dose to manufacture27. In contrast, ophthalmology gene therapy programs typically use far lower doses in the range of \(1 \cdot 10^{11}\) vector genomes, and so cost per dose can be as low as a few thousand dollars. Looking at Spark’s COGs relative to their sales in the table below show that they were able to maintain decent margins.

Table 4: Spark’s COGs as a ratio to sales

| Time period | US sales | COGS | Ratio | Vials shipped | COGS per vial |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 2018 | $2.4m | $121k | 5% | 6 | ~$20k |

| Q2 2018 | $4.3m | $269k | 6% | 12 | ~$22k |

| Q3 2018 | $8.9m | $318k | 4% | 24 | ~$13k |

| Q4 2018 | $11.4m | $300k | 3% | 33 | ~$9k |

| Q1 2019 | $9.8m | $745k | 8% | 28? | ~$27k |

| Q2 2019 | $11.5m | $1.3m | 11% | 34? | ~$38k |

| Q3 2019 | $6.9m | $1.0m | 14% | 20? | ~$50k |

Source: Spark’s SEC filings

While COGs may be a lesser concern for ophthalmology gene therapy developers, there are many other manufacturing related challenges which can easily derail a program, including:28

- Ensuring that manufacturing is appropriately scaled up from small pilot batches to commercial size lots

- Developing a consistent and GMP-compliant manufacturing process

- Gaining access to limited manufacturing capacity at contract manufacturing organisations

- Finding enough people with experience in gene therapy manufacturing

- Dealing with low yields, with high numbers of empty capsids

Supporting the claim of manufacturing as a major obstacle, a recent analysis in Nature reviews drug discovery found that manufacturing and controls issues were the most common cause of disruptions in cell and gene therapy programs (affecting 12% of programs). Ostensibly it is one such manufacturing issue which is responsible for holding back Lumevoq with the EMA, specifically “a technical issue in the manufacturing of the validation batches”.19

Treatment and administration related safety risks

Inflammation and immune mediated side effects have been a constant thorn in the side of AAV gene therapy programs. Almost all gene therapy programs see some degree of inflammation as a side effect, and ~35% of gene therapy clinical trials to date have been associated with serious treatment related side effects29. While the worst adverse events have mainly been seen in programs with high doses of vector genomes, ophthalmology programs have had their fair share of safety setbacks. Notably, a patient even went blind in one eye shortly after receiving Adverum’s gene therapy for diabetic macular oedema. Patients receiving Luxturna have also been reported to develop progressive perifoveal atrophy after administration, albeit without significant visual loss in most cases30.

Ophthalmologic gene therapies need to be delivered to the interior of the eye, which requires specialized and complex surgical procedures be used, which not all centres have the capability to perform. Subretinal delivery has been associated with lower risk of inflammation than intravitreal delivery, so the former is generally preferred. As this video shows, the administration of Luxturna is highly complex and requires substantial surgeon skill to inject the gene therapy bleb under the retina without complications. The photoreceptors in the eye are delicate, and even small or limited duration disruptions resulting from surgery may lead to irreversible damage31. The FDA even acknowledges that in some cases the risk of performing these procedures may preclude the use of a sham surgery control arm in clinical trials under certain circumstances, such as for paediatric patients23.

To close this section it would be remiss of me not to mention the unknown long-term side effects which are a lingering concern with gene therapies, in particular the risk of insertional mutagenesis leading to cancer. It is the potential risk of these emergent side effects that leads regulators to mandate long-term follow-up for gene therapy patients23.

Limited AAV packaging capacity

AAV vectors - the currently dominant transgene delivery vehicle for IRD gene therapies - can carry up to 5kb32 of DNA. However, many IRDs are caused by mutations in genes that are larger than the carrying capacity of AAVs33, a sample of which are shown in the table below.

Table 5: Genes associated with IRDs that exceed AAV packing capacity (>4.8kb transcript length)

| Gene | Transcript length (bp) | Associated IRDs |

|---|---|---|

| ADGRV1 | 19,338 | Usher syndrome |

| USH2A | 18,955 | RP, Usher syndrome |

| ALMS1 | 12,922 | Alstrom syndrome |

| VCAN | 12,625 | Wagner syndrome |

| SLC7A14 | 10,103 | RP |

| CDH23 | 10,085 | Usher syndrome |

| LAMA1 | 9,657 | Poretti-Boltshauser syndrome |

| EYS | 9,498 | RP |

| TEAD1 | 9,430 | Sveinsson chorioretinal atrophy |

| CEP250 | 8,398 | Cone-rod dystrophy |

| IMPG2 | 8,337 | RP |

| GPR179 | 7,980 | Congenital night blindness |

| RP1L1 | 7,973 | RP |

| CEP290 | 7,544 | LCA |

| ATF6 | 7,496 | Achromatopsia |

| MYO7A | 7,462 | Usher syndrome |

| PRPF8 | 7,445 | RP |

| FZD4 | 7,383 | RP |

| COL11A1 | 7,327 | Marshall syndrome |

| ABCA4 | 7,309 | Stargardt disease |

| ATXN7 | 7,285 | RP, Cone-rod dystrophy |

| NBAS | 7,281 | Optic nerve atrophy |

| SNRNP200 | 7,165 | RP |

| RP1 | 7,100 | RP |

| PITPNM3 | 7,086 | Cone-rod dystrophy |

| C2ORF71 | 7,044 | RP |

| PCDH15 | 6,957 | Usher syndrome |

| MKKS | 6,714 | Bardet-Biedl syndrome |

| EMC1 | 6,664 | Visual impairment |

| OPA1 | 6,492 | Optic atrophy |

| TUB | 6,420 | Retinal dystrophy |

| KIAA1549 | 6,283 | RP |

| GRM6 | 6,143 | Congenital night blindness |

| CACNA1F | 6,070 | Cone-rod dystrophy |

| FLVCR1 | 5,939 | RP |

| AHI1 | 5,921 | RP, Joubert syndrome |

| ADAMTS18 | 5,913 | Myopic chorioretinal atrophy |

| SLC24A1 | 5,768 | Congenital night blindness |

| TRPM1 | 5,715 | Congenital night blindness |

| PDE6A | 5,642 | RP |

| KLHL7 | 5,620 | RP |

| TUBGCP6 | 5,612 | Chorioretinopathy |

| TMEM237 | 5,592 | RP, Joubert syndrome |

| CHM | 5,442 | Choroideremia |

| CDHR1 | 5,428 | RP, Cone-rod dystrophy |

| IFT172 | 5,415 | RP, Bardet-Biedl syndrome |

| RPGRIP1L | 5,297 | RP, Joubert syndrome |

| IFT140 | 5,270 | RP |

| CC2D2A | 5,249 | RP, Joubert syndrome |

| HGSNAT | 5,249 | RP |

| RIMS1 | 5,079 | Cone-rod dystrophy |

| COL2A1 | 5,071 | Congenital myopia |

| NPHP4 | 4,994 | Senior-Loken syndrome |

| CRB1 | 4,932 | RP, LCA |

| LRAT | 4,928 | RP, LCA |

| KIF11 | 4,858 | Chorioretinopathy |

| CNNM4 | 4,800 | Jalili syndrome |

Sources: Gene lengths from supplementary table S2 from Van Schil et al., IRD associations from OMIM

Although dual vector AAV approaches are a potential way to deliver larger payloads34, there seems to have been little success with that approach to date. It may be that these targets will remain intractable for AAV-based delivery and alternative delivery vehicles like lentiviruses or lipid nanoparticles will be required for gene therapy to address these targets in future.

Conclusion, and the future of gene therapy for IRDs

In short, we have not seen further approvals of gene therapies for IRDs because late-stage programs have mostly failed due to challenges with efficacy demonstration, and early stage programs have been deprioritized for reasons of safety and/or low commercial opportunity.

It seems natural to speculate that had Luxturna been more commercially successful we would have seen greater investment in follow-on programs addressing other mutations. I find it notable that Spark no longer have any ophthalmologic gene therapies in their active clinical-stage pipeline. Their only IRD program is one in Stargardt disease that has been listed as research stage for a number of years.

Investment and big pharma interest in ophthalmology gene therapies has mostly shifted to complex acquired diseases with larger prevalences. Examples being the 2021 partnership between Abbvie and Regenxbio in wet age-related macular degeneration (AMD) and diabetic retinopathy35, and Novartis’s acquisition of gyroscope in 2021 for their complement program in dry AMD36. The current bear market in biotech is only going to make it harder for companies to raise capital for next-generation IRD programs, and gene therapy developers in particular have been hit hard by spending cuts and layoffs in recent months.

The shift away from investment in IRDs is a shame because gene therapies do provide meaningful benefits to patients with these diseases, and there is an need for new treatment options for the remaining 90%+ of patients with IRDs who suffer from early vision loss without any effective therapies. I’m reminded in some ways of the difficulties experienced in antibiotic drug development, where the low commercial potential of new antibiotics has led to systemic underfunding of antibiotic research and the bankruptcy of numerous antibiotic drug developers.

Taking into consideration the small prevalences, fragmented genetics, and challenges with efficacy demonstration in clinical trials, it seems that some greater degree of regulatory flexibility is a necessary prerequisite to incentivize investment as the costs of development are high relative to the revenue potential of these therapies. Approvals based on biomarkers, gene expression levels or other surrogate endpoints is one way to ease the path to approval that the FDA (and other agencies) are considering. I also wonder whether in future it may be possible to use in vitro data to extend approvals to new gene therapies produced by well-characterized platforms in situations where tiny patient volumes make trials infeasible, Vertex’s label extension in cystic fibrosis based on in vitro data seems a relevant precedent.

On an encouraging note, it does seem as though regulators are starting to pay attention to the limited commercial viability of cell and gene therapies. In recent days the FDA’s Peter Marks even went as far to state that the use of randomized clinical trials for gene therapies in some settings “borders on the absurd”. Gene editing and new delivery vehicles are also showing promise for IRDs and may be able to address the AAV-related challenges of inflammatory side effects and limited packaging capacity. So there are reasons to be optimistic that in won’t be too many years before more gene therapies for IRDs are approved and are able to benefit patients.

-

https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-novel-gene-therapy-treat-patients-rare-form-inherited-vision-loss ↩

-

https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/luxturna ↩

-

https://www.biopharmadive.com/news/luxturna-gene-therapy-eye-leber-lca/609832/ ↩

-

MIT NEWDIGS Initiative. Existing gene therapy pipeline likely to yield dozens of approved products within five years 2017F211.v011. MIT NEWDIGS Research Brief 2017F211.v011. 2017. https://newdigs.mit.edu/sites/default/files/FoCUS_Research_Brief_2017F211v011.pdf ↩

-

https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/statement-fda-commissioner-scott-gottlieb-md-and-peter-marks-md-phd-director-center-biologics ↩

-

https://endpts.com/fda-chief-gottlieb-is-building-a-regulatory-speedway-to-accelerate-gene-therapy-development/ ↩

-

https://sparktx.com/press_releases/spark-therapeutics-enters-into-definitive-merger-agreement-with-roche/ ↩

-

https://investors.biogen.com/news-releases/news-release-details/biogen-announces-agreement-acquire-nightstar-therapeutics ↩

-

https://investors.meiragtx.com/news-releases/news-release-details/meiragtx-enters-strategic-collaboration-janssen-develop-and ↩

-

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41433-021-01842-1 ↩

-

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6308217/ ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4

-

https://abstracts.isth.org/abstract/hemostatic-response-is-maintained-for-up-to-5-years-following-treatment-with-valoctocogene-roxaparvovec-an-aav5-hfviii-sq-gene-therapy-for-severe-hemophilia-a/ ↩

-

https://sparktx.com/press_releases/spark-therapeutics-enters-into-a-licensing-and-supply-agreement-for-investigational-voretigene-neparvovec-outside-the-u-s/ ↩

-

https://sparktx.com/press_releases/spark-therapeutics-sells-priority-review-voucher-for-110-million/ ↩

-

https://www.gensight-biologics.com/2018/04/03/gensight-biologics-announces-topline-results-from-reverse-phase-iii-clinical-trial-of-gs010-in-patients-with-leber-hereditary-optic-neuropathy-lhon/ ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

https://investors.biogen.com/news-releases/news-release-details/biogen-announces-topline-results-phase-23-gene-therapy-study ↩

-

https://investors.biogen.com/news-releases/news-release-details/biogen-announces-topline-results-phase-3-gene-therapy-study ↩ ↩2

-

https://www.gensight-biologics.com/2020/09/15/gensight-biologics-submits-eu-marketing-authorisation-application-for-lumevoq-gene-therapy-to-treat-vision-loss-due-to-leber-hereditary-optic-neuropathy-lhon/ ↩

-

https://www.gensight-biologics.com/2022/01/18/gensight-biologics-reports-cash-position-as-of-december-31-2021-and-provides-operational-update/ ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

https://ir.4dmoleculartherapeutics.com/news-releases/news-release-details/4d-molecular-therapeutics-announces-rare-disease-ophthalmology ↩

-

https://sph.uth.edu/retnet/sum-dis.htm ↩

-

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17113430/ ↩

-

FDA guidance for industry, retinal disorders https://www.fda.gov/media/124641/download ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4

-

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30268864/ ↩

-

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29084330/ ↩

-

Spark therapeutics presentation: Primary Endpoint Development for a Phase 3 Inherited Retinal Dystrophy Gene Therapy Trial ↩

-

https://www.evaluate.com/vantage/articles/analysis/vantage-points/100000-problem-gene-therapy-companies-would-rather-not#:~:text=Another%20contract%20manufacturer%20speaking%20to,them%20at%20least%20tenfold%20lower%E2%80%9D ↩

-

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-020-19507-0 ↩

-

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41587-022-01346-7 ↩

-

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33838313/ ↩

-

https://retinatoday.com/articles/2021-july-aug/lets-talk-about-gene-therapy-for-inherited-retinal-diseases ↩

-

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2839202/ ↩

-

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32561864/ ↩

-

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6523333/ ↩

-

https://news.abbvie.com/news/press-releases/abbvie-and-regenxbio-announce-eye-care-collaboration.htm ↩

-

https://www.novartis.com/news/media-releases/novartis-acquire-gyroscope-therapeutics-adding-one-time-gene-therapy-could-transform-care-geographic-atrophy-leading-cause-blindness ↩