Steelmanning the argument for free drug pricing

Attacking a strawman is a form of fallacious argument in which opponents of a particular proposition attack a weaker, but superficially similar, version of that proposition in order to make it easier for them to “win” the argument. Strawmanning is particularly pernicious when used as a bad-faith rhetorical technique to lead non-expert audiences to false conclusions.

The opposite of strawmanning is known as steelmanning: attacking the strongest form of your opponent’s argument. By wilfully crafting the best argument you can for your opponent you gain a better understanding of their position, and by extension, your position too. Forcing yourself into a good-faith dialectic helps you come closer to uncovering the truth.

Drug pricing is a contentious and emotionally charged topic often subject to motivated reasoning. High drug prices are routinely criticised in the popular media, often for good reason but typically with arguments that lack nuance. So in the spirit of truth-seeking, I thought it would be an interesting exercise to try and steelman the argument for free drug pricing - in effect, arguing for high drug prices. Personally, I tend to find the most convincing arguments to be those for a form of free pricing with regulatory oversight to prevent the worst excesses of rent-seeking behaviour1 - but then again, I do work in the industry so I am biased.

I’ve bolded what I think are the key points of the argument if you prefer to skim those rather than read the whole thing. Do you find it convincing, or not? Let me know on twitter!

Why pharmaceutical companies should be able to price their drugs freely

Pharmaceuticals are an extraordinarily valuable class of goods. In the 100 or so years in which the pharmaceutical industry has existed, we have seen millions of deaths from communicable diseases averted due to vaccinations2 and antibiotics, large declines in the age-standardized cancer3 and cardiovascular’4 death rates, and increasingly, new treatments which have transformed the lives of patients with devastating rare and genetic diseases such as cystic fibrosis and spinal muscular atrophy. These developments have contributed in part to the dramatic rise in life expectancy since the late 1800’s, shown in the graph below.

The evident value of pharmaceuticals makes them highly desirable, and therefore able to command high prices. Opponents of free drug pricing accuse the industry of a form of extortion, that by exploiting their monopoly position drug companies are able to charge effectively whatever they want for life-saving medications and the healthcare system will be obliged to pay. Hence, they argue that prices should be regulated by government in order to reign in the power imbalance between patients and the pharmaceutical industry. To address this concern it is important to draw a distinction between the concepts of price, value and affordability.

It is true that branded medicines can be extremely expensive, with many new drugs launching with list prices of $100,000 per year or above in developed markets. Such prices are clearly unaffordable for the majority of patients out of pocket, so most countries socialize these costs through insurance-based or nationalized (tax-funded) health systems. It is also true that the monopoly power provided by intellectual property laws and regulatory exclusivities5 is one of the conditions that allows for such high prices. However, it does not necessarily follow that such prices are “excessive”.

There are two critical drivers that contribute to the high prices of novel pharmaceuticals, the profit motive of drug companies and the high cost and risk of drug development. Pharmaceutical companies set drug prices in order to maximize their profits in accordance with what they think the market will bear6. The pricing of drugs is only dependent upon costs in abstract terms, in the sense that drugs must have sufficient potential for return on investment to justify the investment in the first place. This may be distasteful to some industry critics, but in a well-functioning market payers will only be willing to pay high prices if they represent good value for money relative to other options; the need to optimally allocate scarce monetary resources among a variety of health interventions imposes a moderating effect on drug prices. It follows that setting a price for a drug that is “too high” is a poor corporate strategy as it will reduce demand and fail to maximize profits.

The desirability of their goods combined with monopoly protections affords pharmaceutical companies strong pricing power, but does this translate into “excessive” profits as some critics claim? Net income (profit) of large pharmaceutical companies is in the range of 10-20%, which is higher most industries and comparable to the margins in the technology industry7. While substantial, pharmaceutical industry profits are not so large that they would allow for meaningful reductions in the prices of medications without rendering the industry systemically unprofitable; an $80,000 per year drug is similarly unaffordable to the average patient as an $100,000 per year drug. This is not even taking into account the hundreds of unprofitable small and medium sized biotechnology companies striving to bring a product to market at great expense, most of which will never recoup their cumulative debts.

We should be thankful that the industry is as profitable as it is, as it allows for companies and investors in biopharmaceutical research and development to make a return on investment, and thus makes it attractive to continue to invest in the sector and produce a steady stream of new medicines. If the industry became less profitable due to price controls, lower productivity, or otherwise, it would necessarily become less attractive as an investment prospect. All else being equal, lower investment in research and development would necessarily lead to fewer new medicines. Profit potential also serves as a signal to efficiently guide investment decisions into medicines which are likely to provide the most value. In other words, profits lets companies know whether a drug is worth developing. Profitable drugs also attract competitors, a natural mechanism for constraining net prices.

Turning to the cost component, drug development is one of the most risk and capital intensive enterprises that one can undertake. Members of the PhRMA trade association (which includes most large pharmaceutical companies) spend ~$80 billion dollars on research and development per year8, or ~25% of revenues9 on average. By comparison, the budget for the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) is ~$60 billion per year10 and the European Research Council spends around a third of its €16 billion (~$16.3 billion) budget on life sciences research11. Most of the money spent by the industry goes towards fulfilling the regulatory requirements for approval, including toxicology and other preclinical studies in animal models and later on the clinical trials in patients. In particular, late stage randomized clinical trials regularly cost hundreds of millions of dollars and take years to complete with no guarantee of success. Historical probability of success rates in the industry indicate that ~92% of programs fail at some point during clinical trials12, and while estimates vary, research and development expenditure per approved drug is likely $1 billion or higher if you account for the costs of failed trials13. Completing a drug development program requires resources far in excess of what the vast majority of non-governmental or academic institutions are able to muster, and without the possibility of eventual profit, no private enterprise would be willing to bear these costs.

Before a drug even gets into patients a large amount of preliminary discovery work and basic research must be undertaken. While much of this work is done inhouse at pharmaceutical companies, the basic research underlying most drugs is originated in taxpayer funded academic laboratories. Some have argued that it is unfair for taxpayers to “pay twice” for drugs, and for pharmaceutical companies to reap the rewards of academic innovation. However, the discoveries made in academic labs are typically only a first step to a final product. Among other activities, scalable and compliant manufacturing processes need to be developed, and medicinal chemists are needed to make tweaks to promising initial “rough drafts” of compounds to improve their potency, bioavailability and reduce the risk of side effects. This preparatory work is costly and must be carried out by highly trained personnel. Furthermore, the main product of pharmaceutical companies is not their molecules, but rather the information14 required to get their products to approval, and the processes to get that drug manufactured and delivered to patients - which academic labs are not well-poised to deliver. A molecule in itself is worth very little without the data to support its clinical utility. As late-stage clinical trials are where most of the cost of development is concentrated, it is fair for the pharmaceutical companies and investors which fund these trials to capture most of the profit, even if they did not make the initial discovery of the drug molecule. Licensing and royalty mechanisms are in place for universities and governments to profit from research that they originate without having to bear the substantial risk of funding clinical development.

A strong, reliable and fair intellectual property system is crucial to ensure that companies and investors remain confident in the possibility of recouping their investment upon drug approval, and for their ability to accurately forecast returns. The trade-off for the short-term legal monopoly period on new drugs5 is that fact that patents and exclusivities eventually lapse, permitting other companies to develop generic versions of the drug. Generics are usually deeply discounted relative to the originator brand; prices that are less than 10% of the original brand price are common in markets with healthy generic competition15. Drugs eventually enter the public domain, contributing to an ever-growing and improving armamentarium of cheap medicines.

Even so, we should expect the prices of new launches to rise over time as companies are forced to pursue more challenging unmet needs and smaller patient populations for whom the ever-expanding set of treatments has proven inadequate. Because it keeps getting harder and harder to find new drugs which improve on the existing standard of care, prices need to ratchet higher to maintain profit margins and justify continued investment. Without the potential for high prices, many rare or hard to treat diseases will never have treatments developed for them.

At this point a critic of free pricing might reasonably object that if benefits of allowing companies to freely price their drugs are so clear, why then the United States the only major market which has allowed it to persist to date? The US is the largest market for pharmaceuticals, accounting for just over 40% of worldwide sales16. It also has the highest prices for branded pharmaceuticals in the world, ~3x higher than other developed OECD countries on average17. It is fair to say that the US has chosen not to optimize their healthcare system for low drug prices. However, the prices that are achievable in the US in effect subsidize drug development for the rest of the world, and are vital for the continued attractiveness of the industry for investment. It is no coincidence that the majority of medical innovation and new drug origination18 takes place in the US biotechnology ecosystem. The US has so far decided to prioritize innovation over cost-containment, and the rest of the world should be grateful that it does.

The alternative to a free-pricing paradigm is one in which governments set prices based on formal “health technology assessment” (HTA) criteria, as is done in Europe, Canada, and Japan among other countries. Different countries use a different mix of criteria, but they usually involve scoring products in terms of degree of clinical benefit or improvement in “quality adjusted life years” (QALY) relative to the standard of care. Drugs with high scores may be allowed to charge a premium on top of the price of standard of care. Those judged to have no or limited added benefit may be forced to set their price equal to the existing standard of care, no matter how cheap it is. HTA processes sound good in theory, however, while they can be effective means of cost-containment they can also introduce perverse incentives.

Foremost of these is the risk that the metric used to score drugs does not capture the full benefit of the drug. Assigning prices based on cost-offsets makes it easier to balance the budget, but it comes with the downside of disincentivizing investment in diseases with a cheap standard of care - even if treatments are inadequate19. QALY and clinical benefit metrics can also systemically undervalue certain hard to quantify improvements in quality of life (e.g. subjective measures like improved wellbeing), and it can be argued that QALY’s actually discriminate against prolongation of life for people with disabilities20. In short, HTA systems involve governments deciding what patients should value in a disease-agnostic manner based on simplified metrics that may or may not be aligned with what patients actually value.

Government price-setting also introduces unfavourable power dynamics with the potential to impede access and investment. Having the power to set prices can enable governments to “play hardball” and refuse to reimburse expensive drugs for political reasons, even if their proposed prices are wholly justified in terms of value for money. Because prices are negotiated and set at the time of drug approval, these processes introduce additional delays in getting the drug to patients (e.g. in France the price negotiation process regularly takes more than a year). They also make it harder to justify investment in the first place as investors have no certainty about how a product will be eventually valued when deciding how to allocate capital. When you consider that governments also set the criteria for market authorisation, price-setting lets governments control both corporate expenditure and revenue.

Having discussed price and value, I will close with a brief discussion of affordability. What patients actually mean when they say that drug prices are too high is that out of pocket costs are unaffordable, such that an insufficient portion of the total costs are borne by the healthcare system. In a well-functioning healthcare system effective drugs are accessible and affordable, and pharmaceutical companies are compensated in proportion to the value they create.

Healthcare systems have two key obligations when it comes to collecting and distributing funds:

- To collect an amount of money from their covered population that is commensurate with their population’s willingness and ability to pay for healthcare, and their expected utilization of healthcare resources

- To allocate collected funds to pay for healthcare for the covered population that maximizes total welfare in terms of value for money, while ensuring that every member has access to an adequate baseline standard of care

This doesn’t mean that all health interventions should be made affordable for whoever wants them using funds from the common pool, as that would mean advocating for unsustainable allocations of maximal funding and resources to any ailment, regardless of diminishing returns. We cannot have it all, but we can aim to allocate the scarce resources we do have as best we can, and the free market is the best means that we know of to effectively make those allocations. Even at high prices, drugs are among the most cost-effective healthcare interventions available. If it so happens that a particular drug does not represent good value for money for a particular patient relative to other options, then we should resist the market failure that would see that drug reimbursed and made affordable.

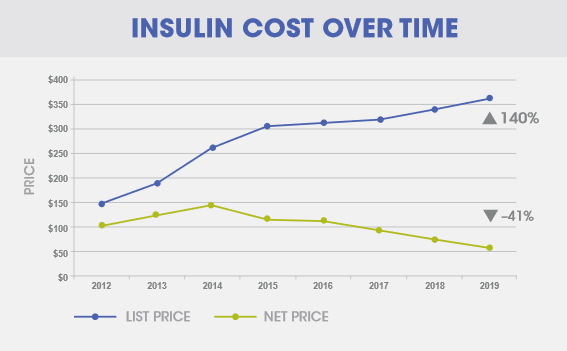

In the US, the developed market where the affordability issue of drugs is most acute, it is often the case that the price a drug company charges for their products is disconnected from the affordability of that drug. When one looks closely, it is usually regulations, inflexible contracting, illiquid insurance markets, rent-seeking middlemen21, and misaligned incentives that prevent the market from operating efficiently. In one of the starkest examples of market failure in recent years, the price that Sanofi receives for their insulin in the US declined by 41% between 2012 and 2019, while list prices and average out-of-pocket costs for patients actually rose22 over the same period (shown in the graph below).

High prices are not incompatible with wide access, and rather than asking why drug companies charge such high prices, we should ask what can be done to lower the cost and risk of development and the barriers to market in order to spur competition and innovation, and what market dysfunctions and perverse incentives are getting in the way of ensuring drugs are affordable and accessible for patients.

Other relevant links:

- The Evidence Base on the Impact of Price Controls on Medical Innovation

- How to kill the conversation that makes innovation possible

- The Questionable Economic Case for Value-Based Drug Pricing in Market Health Systems

- The Great American Drug Deal

- Misguided Rating Cancels Rare Disease Patients

- How Biopharma Companies Use NIH and Vice Versa

- How do prescription drug costs in the United States compare to other countries?

- The debate over America’s drug-pricing system is built on myths. It’s time to face reality

-

Some examples include endless patent evergreening, pay for delay lawsuits, and aggressive price hikes above inflation without additional clinical data to support them ↩

-

https://ourworldindata.org/cancer#is-the-world-making-progress-against-cancer ↩

-

https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/cardiovascular-disease-death-rates-by-age?country=~OWID_WRL ↩

-

The government of most countries recognizes the difficulty of drug development, and so allows companies a lengthy period of market exclusivity (monopoly) in order to incentivize investment. The length of this monopoly period depends on the status of the patents at approval; it typically lasts around 13 years but can be as high as 20 years. Separate overlapping regulatory exclusivities are also often granted by medicines regulators, these are typically 5-7 years in duration however they are generally of lesser importance than patent exclusivity due to their shorter duration ↩ ↩2

-

This is true in a general sense, but there are exceptions. Companies may intentionally choose prices lower than the profit-maximizing price as part of a strategy to avoid “offending” various stakeholders, to drive market share, or to generate goodwill. They may also negotiate discounts as part of a bundled deal for a portfolio of products or agree to various forms of managed entry agreement to facilitate market access or speed up time to market ↩

-

Profitability of Large Pharmaceutical Companies Compared With Other Large Public Companies ↩

-

CBO Report on Research and Development in the Pharmaceutical Industry ↩

-

Not all industry revenues are invested into research and development, and some have maligned the pharmaceutical industry’s spend on marketing and share buybacks in particular. While both are these are not unalloyed benefits for patients, they do have some indirect benefits. Marketing helps raise awareness of new pharmaceutical drugs, data and guidelines among healthcare practitioners who may otherwise have limited time to follow the latest developments closely. Buybacks and dividends function as a means to return capital to investors when the executive team sees little opportunity to achieve attractive return on investment by investing in the further business, this capital then gets recycled to fund other promising opportunities. Aside from these expenditures, companies are also have high compliance requirements to ensure that side effects with marketed drugs are appropriately recorded and reported. They also hire analysts to forecast the demand for new products, and decide how to effectively allocate their capital to drug development programs ↩

-

Clinical Development Success Rates and Contributing Factors 2011–2020 ↩

-

Estimated Research and Development Investment Needed to Bring a New Medicine to Market, 2009-2018 ↩

-

When I say information I mean the applications and dossiers submitted to regulatory agencies like the FDA and EMA, the clinical trial data and the publications of supporting evidence for the benefits and risks of a given drug ↩

-

Pharmaceutical market sizes by countries and regions, multiple sources within ↩

-

The importance of new companies for drug discovery: origins of a decade of new drugs ↩

-

How Current Cost-Effectiveness Analyses Distort Drug Development Priorities ↩

-

Quality-Adjusted Life Years and the Devaluation of Life with Disability ↩

-

A detailed discussion of pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) is out of scope for this post, but it is worth understanding their role in managing access to medicines and negotiating prices in the US as many people in the pharmaceutical industry have accused their practices of causing high list prices and out of pocket costs for patients. This article provides a summary of the common criticisms of PBMs: https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/forefront.20180823.383881/full ↩

-

Net prices for insulins keep dropping, but patients are paying more, Sanofi says ↩