Innovation, sea snails, and the blind professor

“Evolution and economics - different expressions of the same principles that govern life and the emergence of life’s organization show us what works and what does not, which adaptive hypotheses preserve adaptability and opportunity and which lead to rigidity and constraint.” - Geerat J. Vermeij

“All economic revolutions have at their core an enhancement of the supply of energy.” - David Landes

How can a sea snail’s shell be a disruptive technology? In what way can a region of ocean be described as an innovative economy? These are some of the questions that Geerat J. Vermeij tackles in his book “Nature: an economic history” (NaEH).

Professor Vermeij is one of the world’s foremost experts on marine molluscs and an interesting character in his own right; blind since childhood, he studies the diverse shapes and structures of gastropod shells by touch. Throughout his career, Professor Vermeij has had an interest in applying economic concepts to the biological sciences, and NaEH is the synthesis of what he’s learned in the process. In seeking to understand what is true of both productive ecosystems and economies, he has sketched the outlines of a general theory of innovation which I’ll spend most of this post elaborating on, starting with a way of thinking about innovation as a physical space.

Imagine a vast flat plain full of shells of all forms, with closely (evolutionarily) related shells located physically close together. At the centre of this “shell space” you find the first shell to ever evolve, perhaps little more than a stubby scale of calcium carbonate. As you pick your way outwards, you pass steadily more elaborate shells until you eventually reach intricate, beautiful, and highly adapted forms like those of the Murex genus. Sometimes you find regressions in form too: simple shells with complex ancestors. Exploring further, you come across gaps in the landscape for undiscovered shell types, forms that could have existed but never managed to evolve for one reason or another. The shells that surround these voids are nature’s failed experiments; strange or inferior forms that weren’t good enough to propagate.

Man-made inventions can be thought of in a similar way - as points in an theoretical invention space. A quote from “Why Greatness Cannot Be Planned”1 helps visualize the concept:

“The great room of all possible inventions is mostly filled with inelegant doodads, like unreliable machines that occasionally can move a ball from one location to another and pointlessly ring a bell. But if you look hard enough, some areas of the room contain simple yet useful ideas - bags, wheels, wheelbarrows, spears. Rarer still are more sophisticated inventions - in one corner are all manner of cars and in another corner, computers. Somewhere in the room are fanciful machines unlike any we’ve seen before, still waiting to be found.

Let’s visit the pocket of space filled with computers. If you spend a lot of time in this area, an interesting thing begins to happen: You start to understand the shape of this space, how one computer leads to another, like stepping stones along a winding path. Wander long enough, and you may even start to see where the interesting possibilities may lie.”

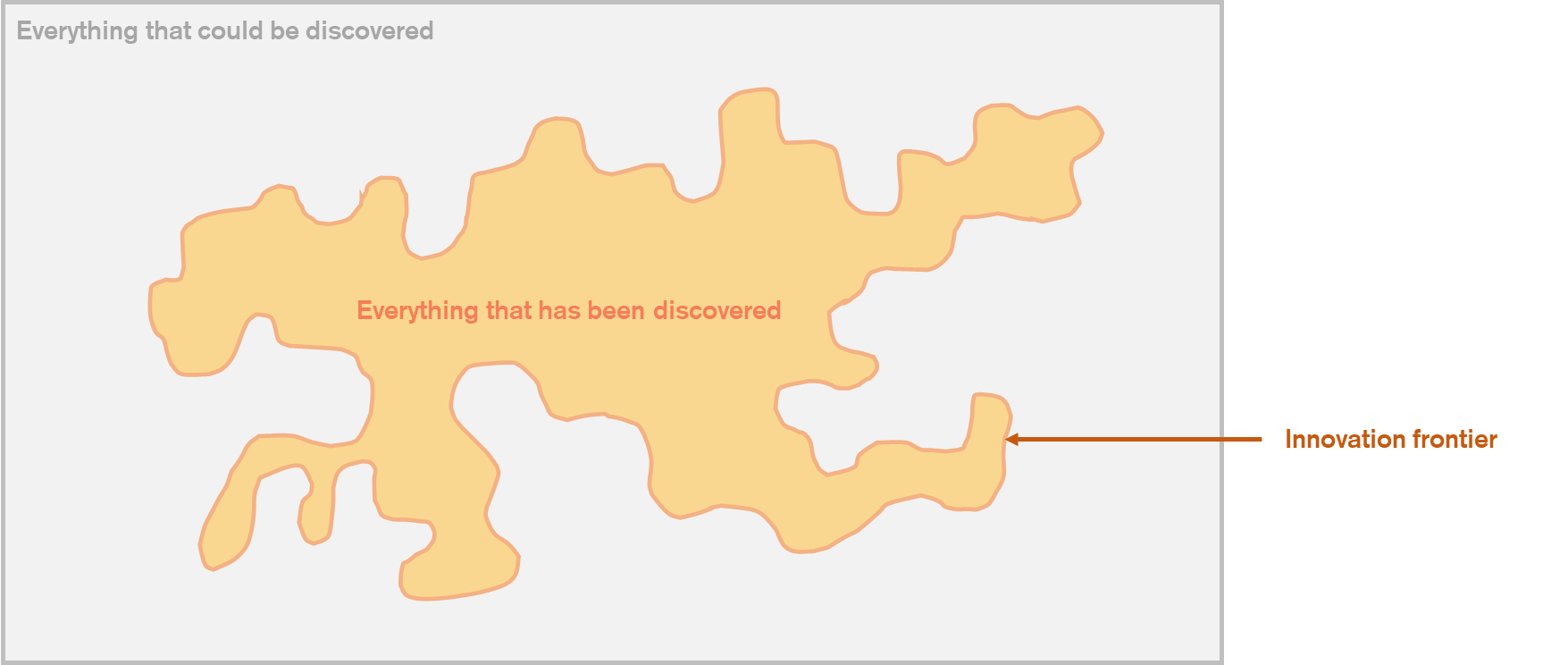

The central insight in NaEH is that the natural conditions and processes of discovery that shape the shell space are fundamentally similar to the human-originated ones that shape the invention space. Using a broad definition of innovation - any new discoveries or inventions - you can think of both spaces as portions of a larger innovation space. In this innovation space, everything that has been discovered is encapsulated by an innovation frontier demarcating the furthest extent of our knowledge. New discoveries incrementally extend the innovation frontier, and everything yet to be discovered lays beyond in a winding maze of dead ends, unproductive cul-de-sacs, and the occasional treasure.

Extending the innovation frontier is path dependent in an unpredictable fashion; each new innovation builds on a chain of prior innovations that are elaborated or combined in unexpected ways. Trial-and-error based tinkering at edge of knowledge is a reliable way to innovate, although you can’t be sure what exactly you will discover, whether it will be useful, and how it will be useful. The further from the frontier you aim to travel, the more uncertain the chain of discoveries that chart the shortest path to the eventual goal. This fundamental unpredictability is at the heart of why basic research is so valuable. As an illustrative example, when two University of Utah undergraduates - Craig Clark and J. Michael McIntosh - went out to collect and study cone snail venom in the late 1970’s they weren’t doing it with the explicit goal of eventually developing a novel non-opioid pain drug. Yet, this turned out to be a productive avenue of research that eventually resulted in the discovery and approval of the potent painkiller Ziconotide decades later23.

Even though the discovery of novel innovations is a stochastic and serendipitous process4, it’s clear that not all environments and systems are equally competent at pushing the innovation frontier outwards. One of the themes throughout NaEH is the differential capacity for innovation across ecosystems, and how this comes to influence the geographic diffusion of innovations. It’s well-understood that highly productive economies like San Francisco’s produce and export more globally competitive innovations than less productive ones, like remote Amazonian tribes. What is perhaps less well-recognized is that analogous circumstances occur in the natural world as well:

“Regions and ecosystems in which productivity is high, competition is intense, and adaptation is least constrained by energetic and material limitations, occur at low to middle latitudes - the tropics and subtropics, in other words - in most lowlands and the shallow waters of oceans near large, topographically complex land masses. These environments and the species living in them economically and evolutionarily subsidize less productive parts of the biosphere with raw nutrients, food organisms, and evolutionary lineages; they thus act as donor regions and dominant species on a geographic scale. Species invade from the tropics to the temperate zone, not in the opposite direction.”

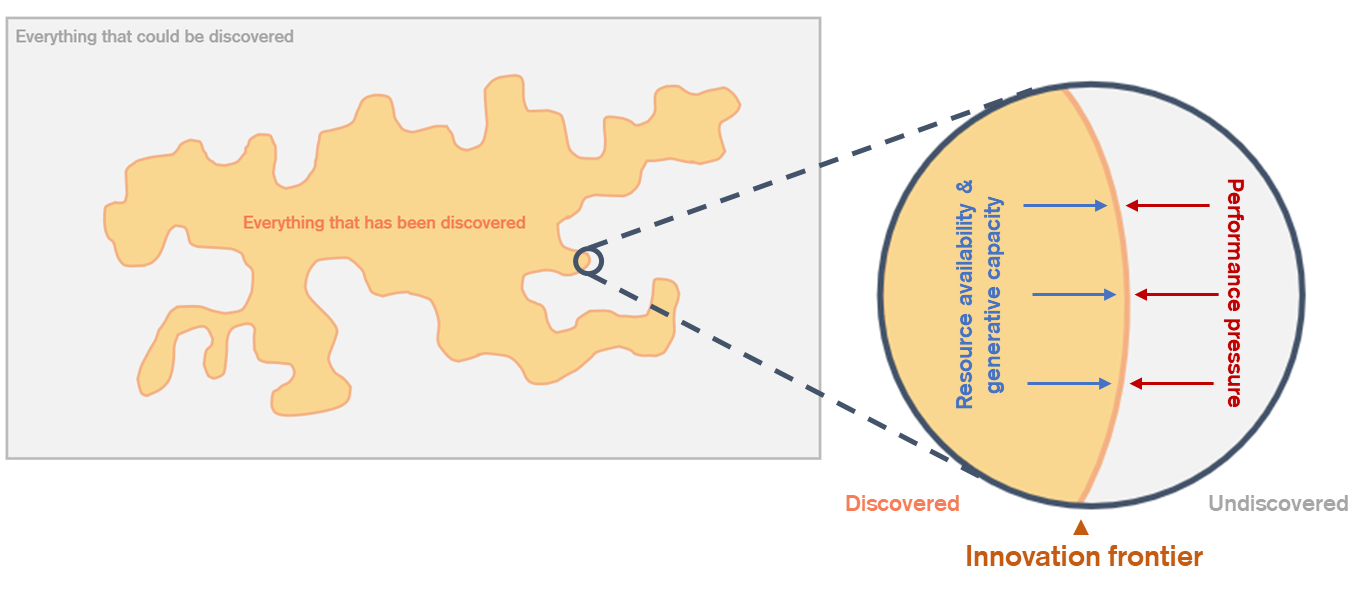

So what determines the innovativeness of a particular economy, regardless of whether it is man-made or natural? Drawing from NaEH and other members of the innovation literature, I propose three core factors: resource availability, generative capacity, and performance pressure.

Any action that opposes entropy requires the input of energy. High performing (i.e. powerful) entities are those that can capture and apply energy in order to resist entropy and shape their environment in their favour. It follows that high performance typically goes hand in hand with high energy expenditure. Since life and living systems require energy to grow, survive, and reproduce, energy is the fundamental resource that all entities are competing for:

“Economic entities succeed or fail through competition for energy (the product of force and distance, expressed in joules) and its material equivalents. It is energy that entities exchange during interactions. Energy is therefore a currency, or a means of exchange, for valuing economic activity. In the monetized economy, money substitutes for energy.”

Entities improve their performance by developing, adopting, and refining new innovations. In biology, the capture of mitochondria and chloroplasts enabled eukaryotic cells to vastly expand their energy budgets and develop multicellularity. In the human economy, general purpose technologies like the domestication of beasts of burden, watermills, wind-powered sails, steam engines, and fossil fuels have each powered explosive increases in the capabilities and reach of our societies5.

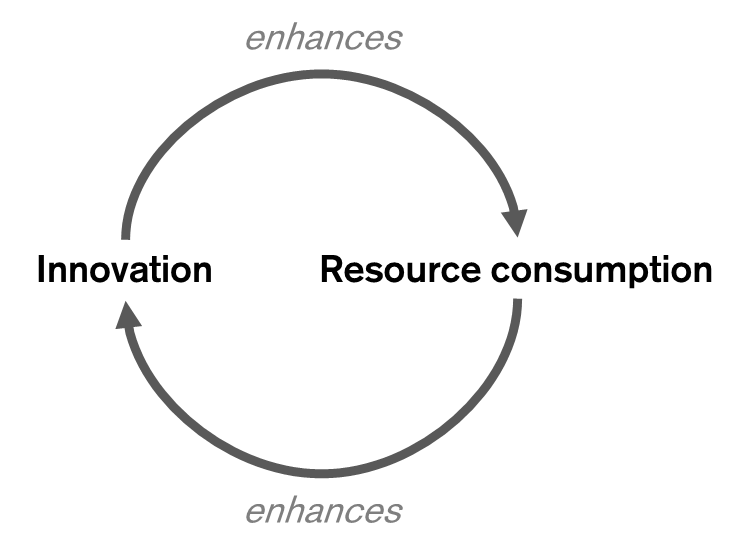

Like any other action, making new discoveries and expanding the innovation frontier also requires the input of energy and material resources. Energy is required for innovation, better innovations drive improvements in the ability to compete and capture additional energy which provides the fuel for further innovation… and so on in a virtuous cycle until all available energy in the environment is captured and put to use. Kicking off this feedback loop is how increases in resource availability fuel innovation.

However, a shift in resource availability is for nothing if agents in the economy are not receptive and ready to capitalize on the opportunity. Generative capacity is a type of intrinsic resource that improves the ability of an entity to generate new innovations. For individual humans, these include things like high intelligence, motivational drive, or education. Human institutions may have high generative capacity if they employ uniquely talented people, are cognitively diverse, or have exceptional technology or processes. For organisms, an expansive genome or a high mutation rate leads to a high generative capacity. Faster generation times of biological organisms also means faster adaptation, analogous to how rapid iteration and prototyping speeds up the invention process. Generative capacity also scales with the number of prior innovations, as each pre-existing innovation can serve as inspiration or fodder for future inventions. The greater the circumference of the innovation frontier, the greater the number of undiscovered innovations abutting it.

Boiled down to its essence, generative capacity is a measure of the degrees of freedom (i.e. versatility or optionality) available for an entity to productively use in the discovery process. High degrees of freedom increase the breadth of solution space that can be explored, and because innovation relies on random sampling at the innovation frontier (i.e. tinkering), broader sampling increases the likelihood that the sample space includes a truly useful discovery. An example of this principle is how the decoupling of different shell regions in molluscs allowed a greater diversity of shell shapes and functions to eventually evolve:

“Versatility in organic form is often achieved by decoupling one structure from another or by breaking dependencies of one function on another… molluscs originally had multiple zones of skeletal formation, in each of which more of less identical spicules of calcium carbonate are laid down… A mutation affecting one sector of the shell-secreting mantle margin would affect the entire structure. In more derived clades such as the Sorbeoconcha, the single shell has been divided into two or more domains. Modifications of the anterior end the accommodate a cancel of the siphon, for example, do not affect more posterior sectors. Differentiation like this not only increased the functional versatility of the shell, but also greatly increased the range of shell shapes.”

Generative capacity is a latent resource, it needs other resources on which to act to generate innovations and its potential is squandered in a poor environment. The inverse is also true, a lack of generative capacity despite high levels of resources will mean that these resources are simply wasted or sit unused. At a high level, this is the reason why many corporate or government innovation initiatives fail. Consider efforts to create novel biotechnology clusters which have been universally unable to mount any significant competition against the main Boston and San Francisco hubs due to a lack of talent, key support structures, and institutions, despite large capital investments.

Our last core factor is performance pressure, or how tolerant the environment is of suboptimal performance. In some environments, competition for resources and selection pressure is intense - poorly performing innovations are rapidly rooted out and species are forced into hyper-specialised niches, or driven to extinction. Innovations may even be lost as the innovation frontier is pushed back. Many other environments are relatively gentle, allowing organisms that are “good enough” to thrive in broad niches under minimal selection pressure:

“In the western Pacific and Indian Oceans, dozens of species of [predatory cone snails] co-occur, each one more or less specialized to a rather narrow range of prey. There are specialists on other snails, on fish, various groups of segmented worms, and even one (Conus imperialis) limited to fireworms. On Easter Island, however, there is only a single species (Conus pascuensis), whose diet contains members of seven phyla, a far greater range than is eaten by [other similar snails].”

A natural environment that was infinitely permissive - a so-called “gentle Earth”1 - would be extraordinarily innovative with a wild proliferation of all manner of bizarre and experimental creatures, but the vast majority of its inhabitants would not be performant nor efficient, even though it would likely contain a small number of truly fearsome competitors. In low selection pressure environments, organisms have the freedom to experiment and accumulate variations unimpeded. Environments with abundant resources tend to produce more types of organisms, and eventually better competitors, as these new variations provide plenty of raw material to tinker with. The trade-off at the other end is that while high performance pressure environments have better competitors on average (because low performers are culled), this comes at a cost of lower overall innovation. New innovations are unlikely to meaningfully increase performance at first and may be detrimental or costly to implement, but they provide the raw material for future development and performance gains (e.g. dinosaur feathers eventually being co-opted for flight)6. Competitive environments focus and optimize, permissive ones allow diversity to flourish - even non-productive diversity.

Resource availability, generative capacity, and performance pressure all interact to determine how difficult it is to innovate within a given system. To get a sense of how these factors interact, imagine the innovation frontier as a balloon. Resource availability is like the air pressure inside the balloon, blow in more air and the balloon expands. Performance pressure is an external force pushing on the surface of the balloon, trying to stop the frontier from growing, like hands compressing the balloon and the air inside. Generative capacity is then a sort of unevenness in either resource availability or performance pressure leading to places where it’s easier to push the frontier outwards, like when you squeeze a balloon and bulbous pockets of air expand into the gaps between your fingers.

These factors all combine to determine an innovation surface area: the region of the innovation frontier along which progress is being made. Generative capacity defines where you are pushing on the frontier, resource availability how hard you are pushing, and performance pressure how hard the environment and other competitors are pushing against you.

We can be confident that a system with a large innovation surface area will produce many innovations7, some of which will be exported and adopted elsewhere if they provide advantage. Innovation frontiers are not uniform from one environment to another. While competition may be local initially, successful innovations eventually diffuse outwards and replace lesser ones in less productive economies. Professor Vermeij gives the example of the labral tooth8 - a weaponized spike present on some predatory snails - to illustrate the general rule of how performance-enhancing innovations tend to originate and spread:

“Although some snails with a labral tooth live in cold-temperate shores in such places as southern Chile, south-eastern Alaska, and southern New Zealand, all instances origin of the labral tooth occurred in tropical or warm-temperate waters. Of 46 origins after 34 Ma (the end of the Eocene epoch), all but one were on productive continental coastlines.”

The labral tooth’s prevalence in the fossil record made it a convenient object of study for Professor Vermeij to measure the diffusion of innovations, but the patterns he observed are hardly unique. Across the natural and human worlds there’s a trend towards greater complexity and performance over time with new innovations continually supplanting old ones. The tendency of productive economies to be net exporters of high-performing innovations brings about global uniformity; less productive economies adopt what works and thereby come to mimic more productive ones, albeit without the same capacity to generate new innovations of their own. The fewer barriers to the spread of innovations, the quicker the best innovations come to dominate. This is one of the reasons why the internet has facilitated winner-take-all competition when it comes to platforms and content producers.

The ebb and flow of the innovation frontier as particular systems sequentially adopt or reject particular innovations tends to follow a common pattern, an innovation macrocycle, that recalls Thomas S. Kuhn’s concept of the paradigm shift and the theory of punctuated equilibria.

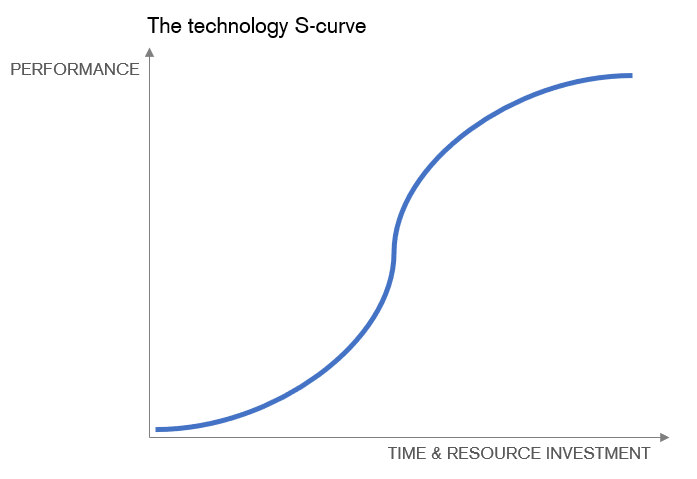

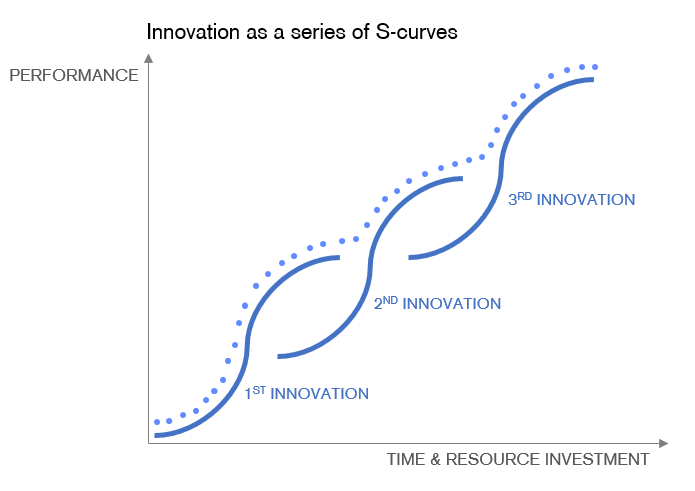

First, an innovator finds a weak point in the innovation frontier and pushes through, discovering some new innovation. Like most other technologies, this new innovation’s performance as function of time and resource investment follows an S-shaped sigmoid curve.

Although not as performant as other old but optimized innovations at first, this new innovation has a higher potential performance ceiling. The rate of improvement in performance is rapid early on, and soon enough the new innovation has matured enough to allow its wielder to outperform its contemporaries and capture large amounts of energy and become a locally dominant competitor. Slowly, the innovation becomes harder and harder to further improve. The performance ceiling is reached and ever increasing resource investments are required to improve or even maintain performance. Performance gains stall. The innovator’s current position is contingent upon a chain of prior innovations and refinements that made them successful in the first place, and maintaining those contingent structures exacts a high burden. “Deep” traits get locked in. This contingency narrows their capacity to explore a new region of the innovation frontier, they’ve over-optimized into a local minima and redirecting resources away would decrease their overall performance - they’re trapped. Somewhere else, another innovator has found a promising weak point in the innovation frontier…

Over time this macrocycle leads performance to ratchet upwards as new and better innovations are sequentially adopted, shown in the below diagram adapted from a 1992 paper by Clayton Christensen9. In a real environment where resources are limited, a macrocycle analogous to heating and annealing is the best for fostering long-term innovation because it biases the system towards building off of productive innovations. Periods of high resource availability allow new innovations to sprout and periods of high performance pressure cull off inefficient energy-sapping innovations ahead of the next cycle.

For the innovation macrocycle to be kicked off and sustained the environment must tolerate or even encourage new but unoptimized innovations. Professor Vermeij suggests two circumstances when this can be the case:

“(1) There must be economic disruption or a permissive environment of sufficient free energy and material resources to provide the capital and the room for error that are necessary to allow innovations to arise and improve (2) There must be sufficient competition - demand - to serve as the selective agency favouring the large investments needed.”

I would add a third, that new innovations can allow entities to succeed by adopting a strategy that is orthogonal to dominant approaches. By an orthogonal strategy I mean one which achieves a particular outcome by optimizing along a different set of performance axes than the dominant strategies, either by attacking a problem in a unique way, growing into a new niche, or making use of an new untapped resource. Companies that develop “disruptive technologies” are adopting an orthogonal strategy; As Clayton Christensen puts it in “The Innovator’s Dilemma”:

“Occasionally, disruptive technologies emerge: innovations that result in worse product performance, at least in the near-term… Disruptive technologies bring to the market a very different value proposition than had been available previously. Generally, disruptive technologies underperform established products in mainstream markets. But they have other feature that a few fringe (and generally new) customers value.”

The other class of orthogonal strategies are those that make use of new or underutilized resources like how molluscs and other early animals put abundant calcium in the seas to use as a novel resource to grow shells and skeletons:

“The evolution of organisms capable of secreting mineralized skeletons beginning about 565 Ma during the latest Proterozoic eon ushered in a fundamental increase in the control of silicon and calcium by life. Minerals of these elements formed with little of no intervention by organisms through crystal growth on the seafloor before organisms put them to defensive use in skeletons.”

By making use of new resources, these early organisms gained a defensive advantage over their competitors and therefore outcompeted them. Many years down the line, their shells became a new resource for other organisms to use in turn:

“A variation on this theme is the use of empty shells. When snails die, they leave behind empty shells, which turn out to be highly effective fortresses for many crustaceans (hermit crabs, amphipods, and tanaids), some worms (sipunculans), some octopuses, and even a few fish.”

The virtuous cycle of old innovations creating the conditions for new ones leads to economic diversification and a trend towards an increase in power and interdependence over time; a “red queen” effect where the standards are continually being raised:

“Potentially at least, every new type of unit created in a diversifying economy itself becomes a resource which another entity could exploit as a habitat, source of energy, or ally.”

Because of this virtuous cycle, it’s fundamentally unclear where the limits to growth and performance lie. Innovation continues for as long as there are resources, the will and capacity to use those resources, and a tolerance for imperfection.

Books that heavily influenced this post:

- “Nature: an economic history” by Geerat J. Vermeij

- “Why Greatness Cannot be Planned: The Myth of the Objective” by Kenneth O. Stanley and Joel Lehman

- “Growth: From Microorganisms to Megacities” by Vaclav Smil

- “The Innovator’s Dilemma” by Clayton Christensen

- “Good Enough: The Tolerance for Mediocrity in Nature and Society” by Daniel Milo

- “Contingency and Convergence: Toward a Cosmic Biology of Body and Mind” by Russell Powell

-

This concept is adapted from a discussion in the book “Why Greatness Cannot be Planned” by Kenneth O. Stanley and Joel Lehman ↩ ↩2

-

https://archive.sltrib.com/story.php?ref=/healthscience/ci_2521679 ↩

-

The history of pharmaceuticals provides ample examples of basic research and tinkering leading eventually to medicines, often in situations when drug discovery was not an explicit goal of the research. When the chain of discoveries leading to the FDA approval of “transformative” medicines is traced back it takes about ~30 years on average from the first basic discovery to the eventual FDA approval (see here). Similarly, it is entirely unintuitive that the study of extremophile Archea would eventually lead to the discovery of efficient gene editing via CRISPR (see here for an interview with the scientist who named CRISPR) ↩

-

For a history of energy, I recommend Vaclav Smil’s Energy and Civilization ↩

-

“Good Enough: The Tolerance for Mediocrity in Nature and Society” by Daniel Milo ↩

-

Why are start-ups more innovative than megacorps? It’s not necessarily true that that’s the case, but small firms are better at sampling across the whole “product space” at the innovation frontier and finding global performance maxima, simply because there are so many diverse start-ups. A single start-up has a small innovation surface area, but many have a large one in aggregate ↩

-

The labral tooth is a spine on the shells of some predatory snails that’s used to wedge apart the protective coverings of barnacles, mussels and other bivalves and speed up the time it takes to subdue them. See here for further details, a paper which contains a nice discussion of innovation in its own right ↩

-

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1111/j.1937-5956.1992.tb00001.x ↩