Intelligence as efficient model building

“There is a fundamental link between prediction and intelligence” - Demis Hassabis

“You insist that there is something a machine cannot do. If you will tell me precisely what it is that a machine cannot do, then I can always make a machine which will do just that!” - John Von Neumann

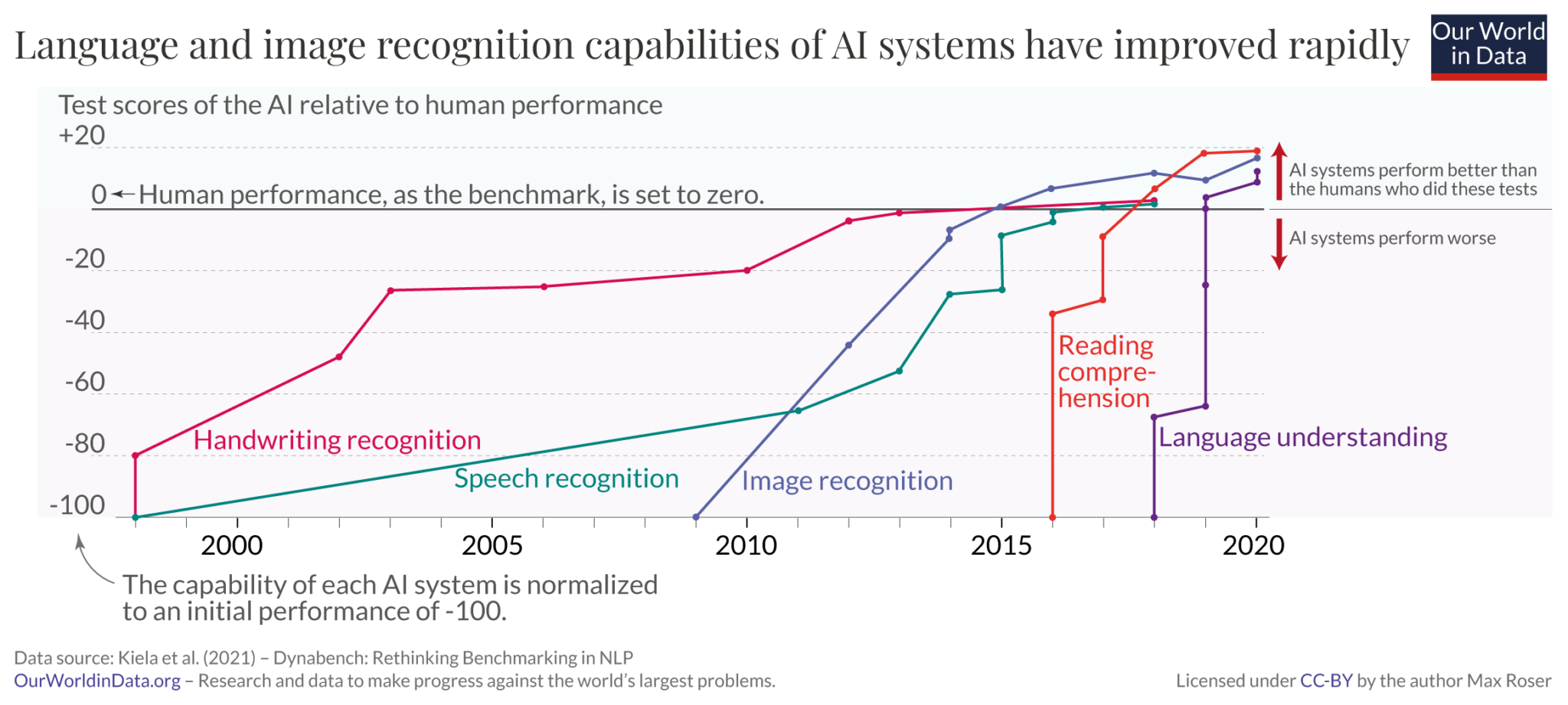

Gradually, then suddenly. After years of grinding progress in artificial intelligence (AI), we now find ourselves, seemingly overnight, in a world in which AI agents can perform broad general tasks at a level approaching or exceeding that of a human.

The most dramatic recent gains in AI capabilities have come from large language models (LLMs) like ChatGPT that apply the “transformer” architecture to digest and regurgitate reams of text data. The hardware and design of LLMs seems to have little in common with the human brain, yet they can emulate human-produced text and reasoning closely enough to make the Turing test seem like a historical irrelevancy. Did we ever really think that would be a good way to determine AI-human equivalency?

Modern AI is clearly intelligent in some sense of the word, but how? Are there many paths to intelligence? What even is intelligence?

One attempt at a mainstream definition of intelligence, signed by a group of 52 experts assembled in 1994, is:

“Intelligence is a very general mental capability that, among other things, involves the ability to reason, plan, solve problems, think abstractly, comprehend complex ideas, learn quickly and learn from experience”1

Another common class of definitions place emphasis on generalizability and goal achievement:

“Intelligence measures an agent’s ability to achieve goals in a wide range of environments”2

I’ve picked out two prominent examples, but there is by no means a fully satisfactory, broad consensus definition of intelligence. Intelligence has proven to be a slippery concept, and given our historical reluctance to cede ground to non-human entities some might even define it as something like “the cognitive ability that is unique to humans”. As AI systems catch up and even overtake us on cognitive tasks that were previously the sole domain of humans (chess, Go, language, programming…) we may soon need to come to terms with the uncomfortable realisation that intelligence is a general capability in which humans are not uniquely well-endowed.

I have an intuition that concepts from Bayesian inference, the free energy principle, and algorithmic information theory could provide a path towards this general understanding of intelligence, and my goal with this post is to explore that path, and with it, a conception of intelligence that goes beyond high-level qualitative definitions. To start us off on the journey, I want to introduce a way of thinking about intelligence as a player in the process through which one system models another.

Bridges between model building, intelligence, and knowledge

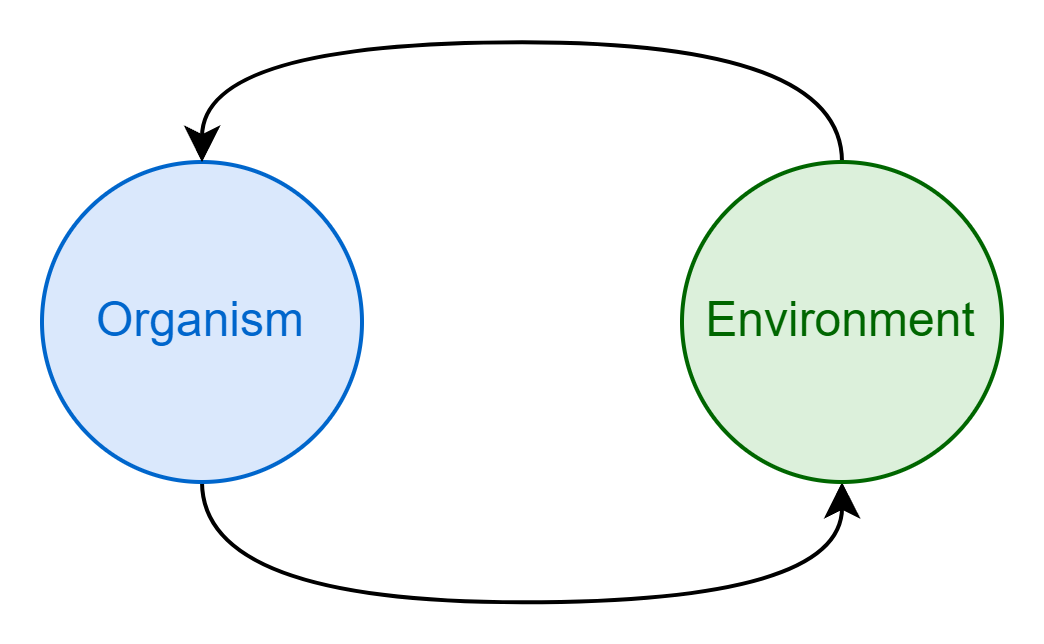

Consider a discrete system - a cell perhaps, or a jellyfish - embedded within another larger system: an organism in its environment. Because these two systems are in contact they exert a mutual influence on one another. The environment acts on the organism, causing it to react and change (imagine a jellyfish twisted and turned about by strong ocean currents). Simultaneously, the organism acts on the environment, reshaping it in turn. It is through this reciprocal action and reaction that information comes to be shared between the two systems3.

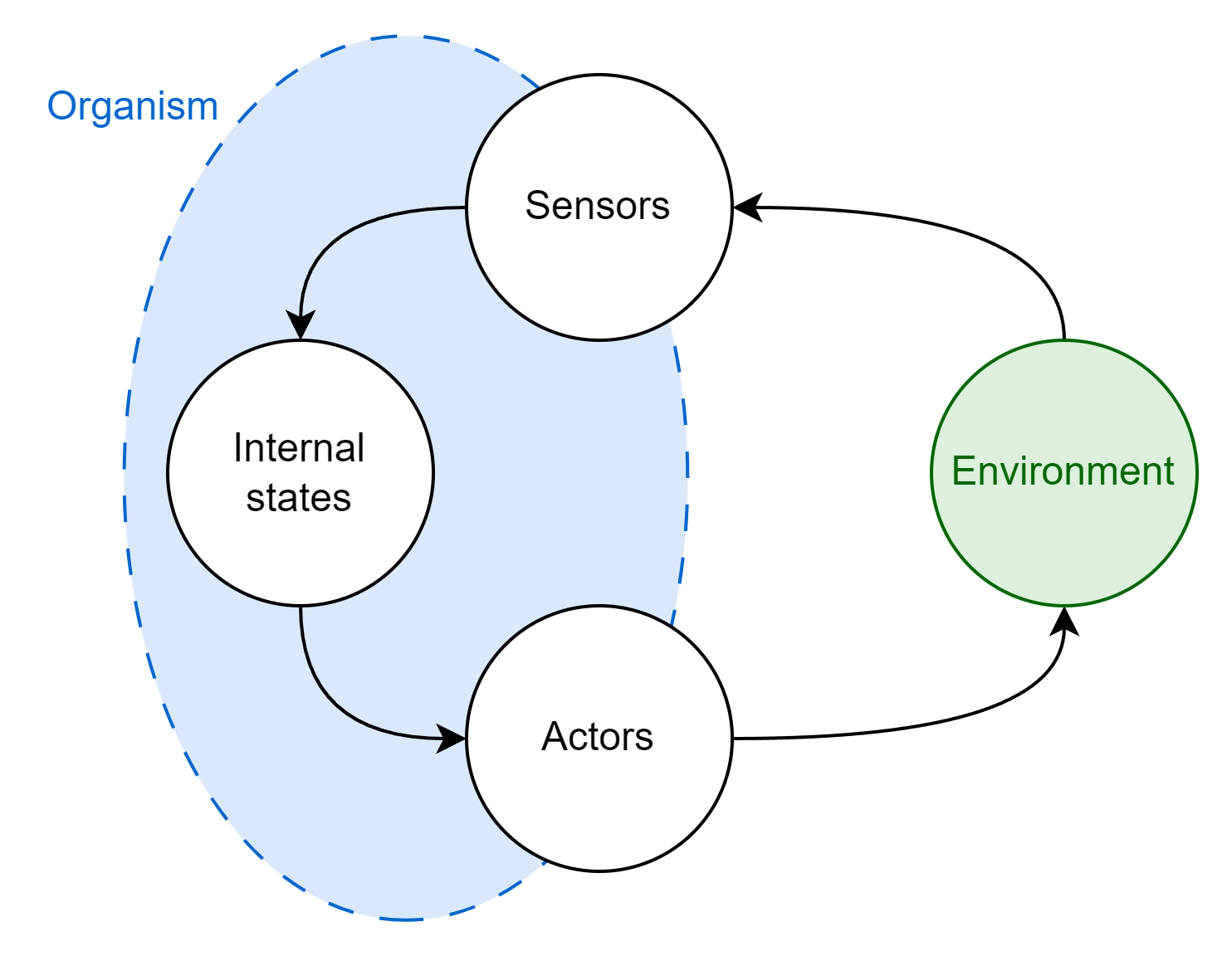

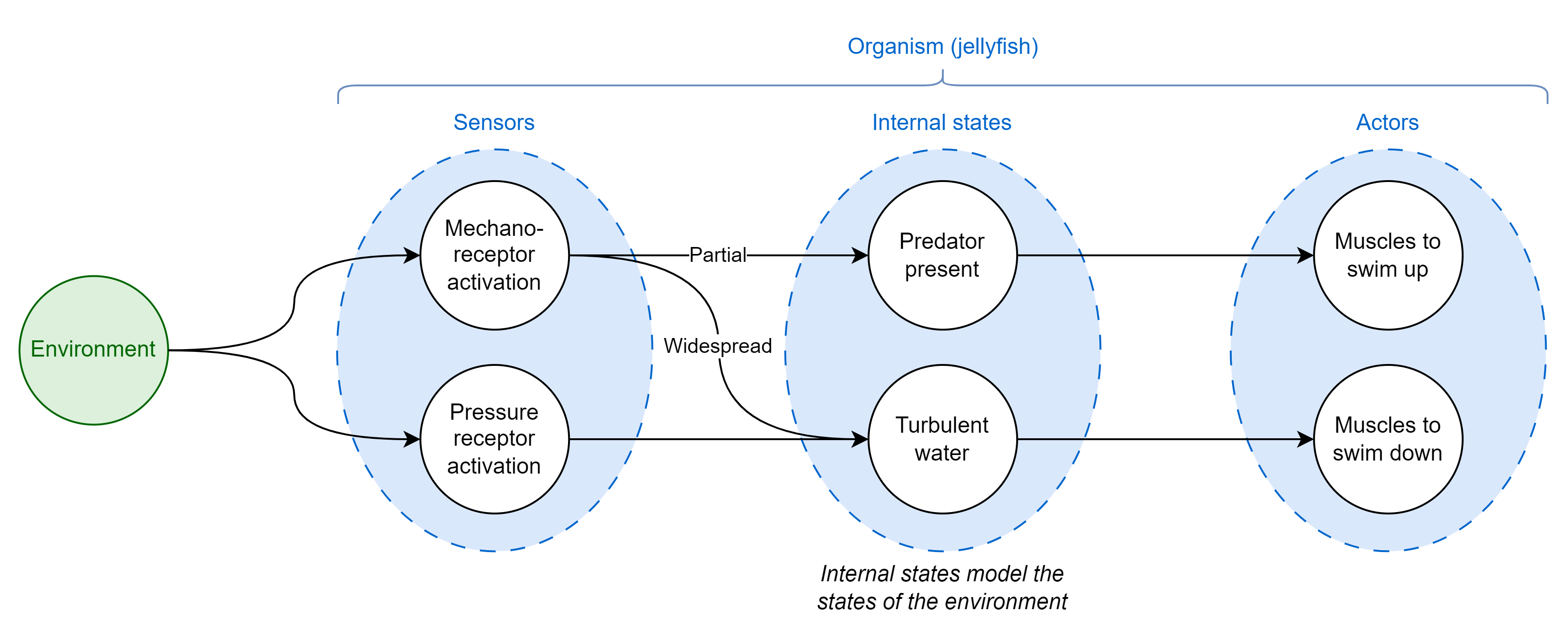

Our organism is a discrete entity, and so it must have some boundary separating it from the environment. In other words, it must have an inside and an outside. We can think of the units that form the environmental boundary as belonging to two broad types:

- Sensors that take in sensory information from the environment, passing that information inwards (e.g. a photoreceptor)

- Actors that do something to the environment, passing information outwards (e.g. a flagellum)

Sensors and actors envelop the internal states of the organism, shielding them from the direct influence of the external environment4. I’ll be using the term internal states to refer to the information that organisms encode about their environment5 which helps them determine what actions to take when presented with particular sensory observations. Internal states are abstract, but they may be reified in the enclosed information processing parts of the organism: transcription factors, signalling pathways, neurons, brains, and so on.

The information that the environment shares with the organism is captured by sensors and recorded in internal states. This is learning through observation, in the abstract. An organism that does a good job of updating its internal states in accordance with its information endowment will select better actions, be fitter, and will be more likely to propagate.

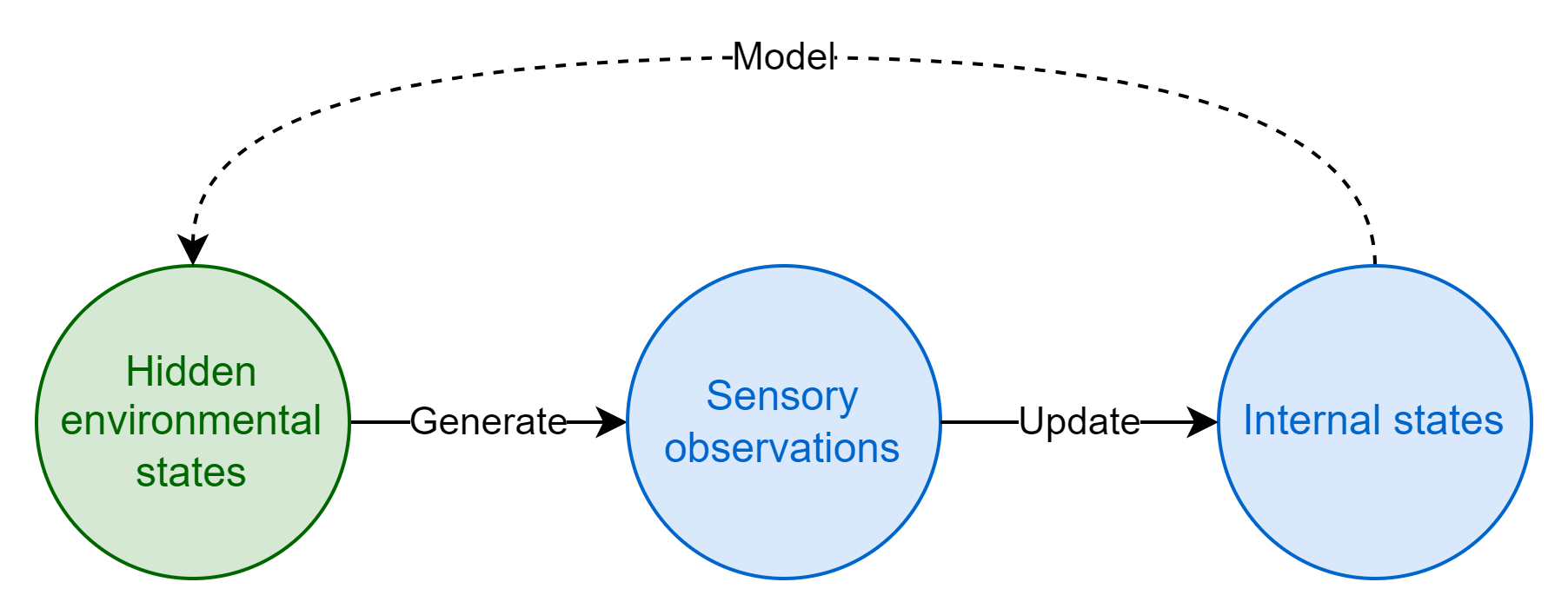

Much like with the organism, we can think of the environment as having its own enclosed set of hidden environmental states that determine its evolution (whether deterministic or probabilistic). These hidden environmental states are akin to the rules or physical laws of the environment; given prior states and accounting for any perturbations from outside forces, they determine how the environment evolves over time, the sensory data it generates, and how it responds to actions taken by the organism. I refer to these states as hidden because for the most part they aren’t directly observable, they are the latent variables behind sensory observations. We might imagine that underneath the “blooming, buzzing confusion”6 of a particular environment, there is some simpler (but probably still extremely complex!) underlying mathematical function that describes the probability distribution of environmental states and resulting sensory data7.

An organism with perfect information on the hidden states of its environment would have a strong fitness advantage as it could use that information to optimally predict future environmental states and thereby reliably select fitness-maximizing actions. In practice, however, organisms only have access to the information picked up by their sensors - they cannot observe hidden states directly. Although sensory observations are noisy and limited in scope, they do leak some information about the true (obfuscated) nature of the organism’s environment. If there are statistical regularities in sensory data it means there is an underlying structure to the environment, and it is in principle possible to figure out this underlying structure. With enough observations, organisms can build up a model of the hidden environmental states that serves as a good-enough approximation of the ground truth to enable effective action selection. This is what the organism’s internal states really are: a model of their environment8. Learning is the process of peering through noise and complexity to figure out the underlying rules of an environment and approximating them, thereby enabling predictions to be made about the future. Learning is model building9.

Building models provides a means for organisms to understand and navigate their environments by learning the underlying structure and patterns, rather than just memorizing specific sensory inputs and matched output actions. Although the true hidden states of their environments may be fundamentally abstract unknowable concepts, or they may be so complex that they are incomputable, organisms can get around these limitations by building internal world models that fit sensory data to computable approximations of the real environmental states.

I’ll return to the jellyfish example for a moment to provide a more concrete illustration of how internal states could model true environmental states. Aurelia sp. jellyfish swim down to hide from turbulent water and up towards the surface to avoid predatory jellyfish if lightly touched by a tentacle10. How might these jellyfish use their limited sensory capabilities, mechanoreception and pressure sensing among them, to decide between two opposite potential courses of action? One conceptual way could be to have an arrangement of sensors, actors, and internal states similar to the diagram below that visualizes the flow of sensory data through to action:

This toy example illustrates two key principles:

- Organisms segment and bundle continuous environmental data (like water pressure) to encode higher-order concepts that don’t really physically exist in the world but are still useful for decision-making (when does a pile of sand become a pile? When it’s big enough for the distinction to be useful)

- Organisms won’t necessarily care to model all the states of their environment, just the ones that are useful for fitness-affecting decisions

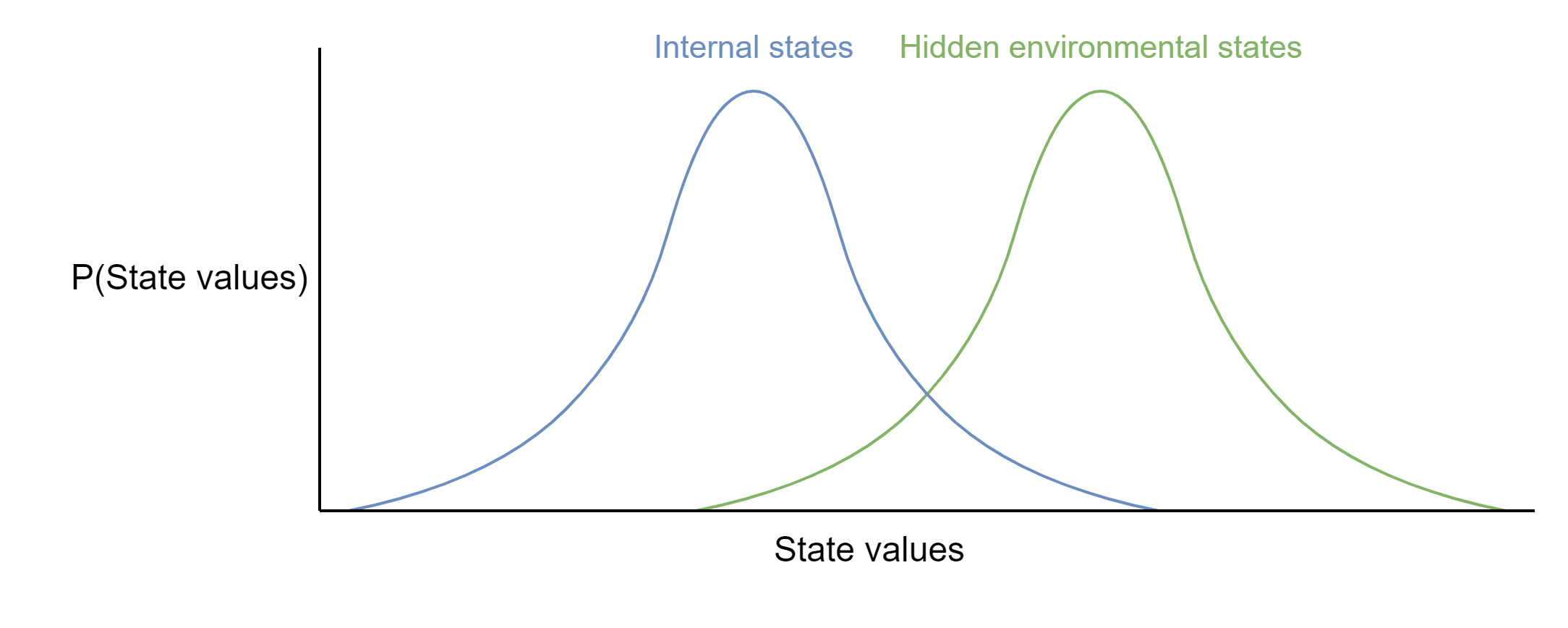

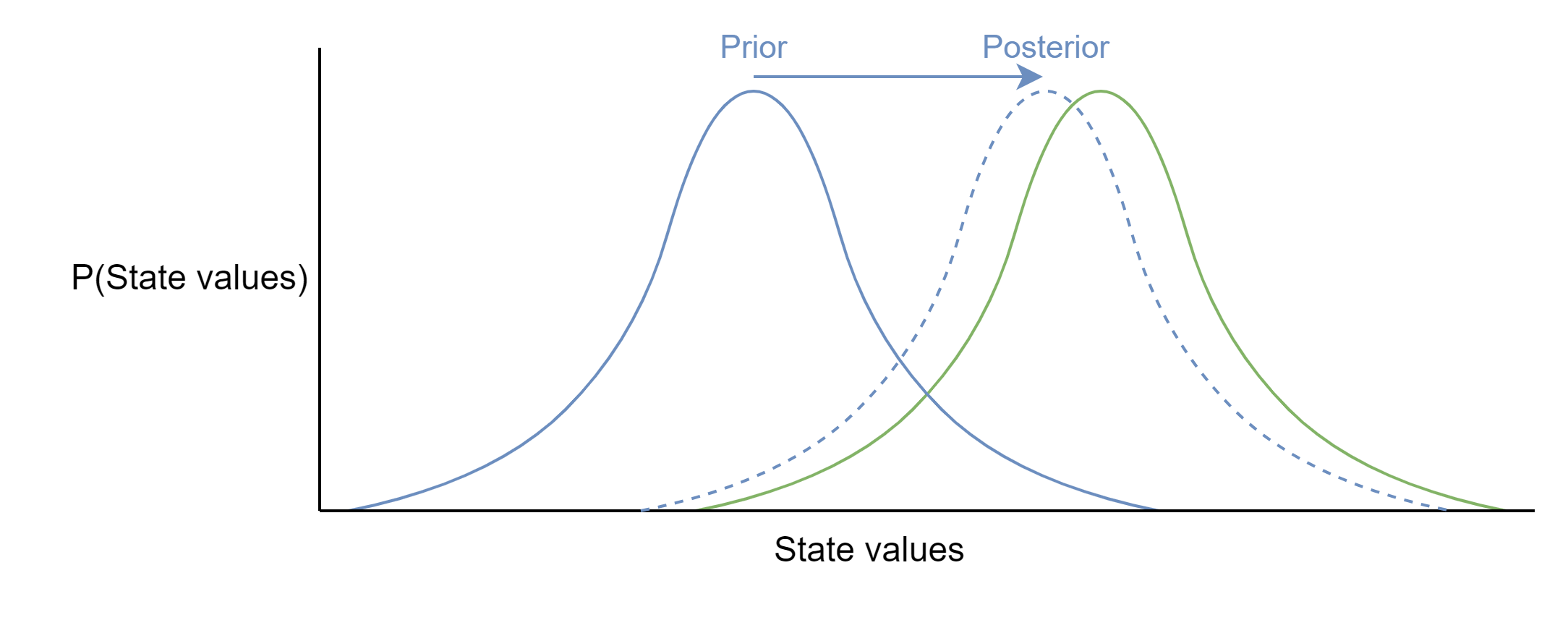

This is just a simple diagram, but I want to think in more general terms, and that means we need to think about the models that organisms build as mathematical objects. Imagine two probability distributions: One representing the ground truth probability distribution of values for a particular hidden environmental state - for instance, the degree of turbulence of the surrounding water - and the other representing the organism’s internal model of that same environmental state. This could be extended in principle along multiple dimensions for any arbitrary number of states that are being modelled. These two distributions are unlikely to be well-matched from the outset; true environmental states are hidden and the organism cannot simply adopt the true distribution, it can only start with a best-guess model.

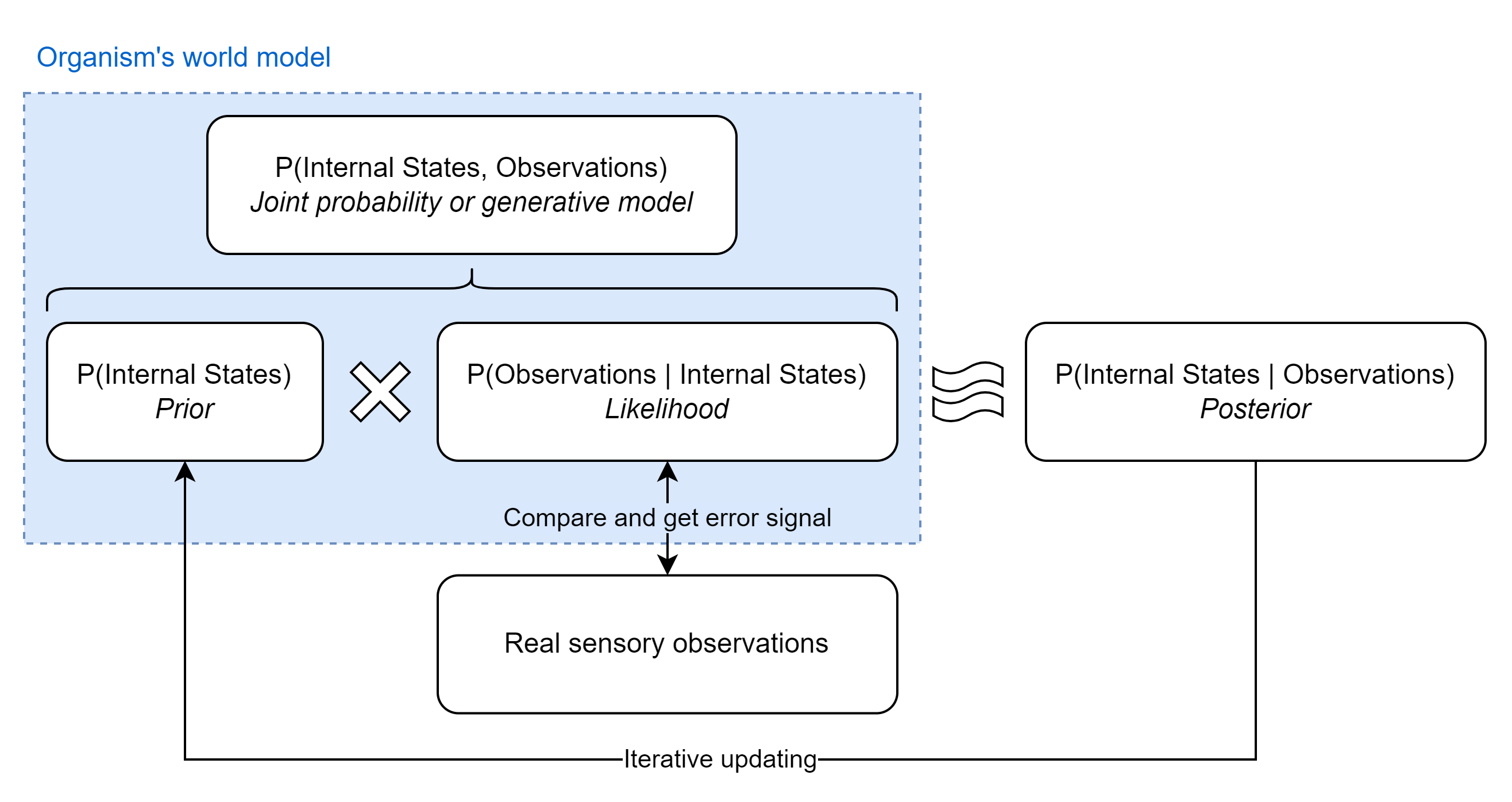

In building its world model, the organism’s goal is to update its internal states to better approximate the true distribution of hidden environment states. That is to say, its aim is to determine the probability that its internal states are correct given the sensory information it has collected. There’s an elegant way to do this mathematically with Bayes’ theorem, which can be thought of as a “formal mechanism for learning from experience”:11

Breaking down the equation into its constituent parts, we have:

- The posterior, \(\small P(\text{Internal states} \vert \text{Observations})\): The probability that a particular configuration of internal states are correct representations of the true hidden environmental states, given the data from sensory observations. How good is the organism’s model of its environment?

- The prior, \(\small P(\text{Internal states})\): The probability that a particular configuration of internal states are correct representations of the true hidden environmental states in isolation. This is the prior plausibility of the model before making any new observations

- The likelihood, \(\small P(\text{Observations} \vert \text{Internal states})\): The probability of observing the sensory data, under the assumption that a particular configuration of internal states correctly represent the true hidden environmental states

- The evidence, \(\small P(\text{Observations})\): The probability of observing the sensory data marginalized over every possible configuration of internal states. Essentially the weighted average of the predictions of every possible configuration of internal states. By dividing this out, the probability of the internal states independently of the probability of the sensory data can be calculated

Each of these constituents should be thought of as probability distributions, rather than single probabilities (although they can be both and the math still works out).

In principle, the organism could try out a few different configurations of its internal states, calculate the probability that each configuration is correct based on its sensory observations, and pick the most probable configuration to take forward. In other words, it should evaluate the most probable internal states over a distribution of possible internal states. If the organism keeps iteratively updating its model of the environment in this way it should eventually come to a good approximation of \(\small P(\text{Internal states}) \approx P(\text{Hidden environmental states})\) without ever needing to observe the hidden environmental states directly.

In practice, however, there is a major problem with applying Bayes theorem to calculate the posterior: It’s almost definitely computationally infeasible to directly calculate \(\small P(\text{Observations})\) because this would mean the organism has to generate every possible configuration of internal states (every possible model of the environment) and their associated probability distributions, then work out the predicted probability distributions of sensory observations given each configuration, and finally calculate the weighted probability distribution of the whole ensemble.

Fortunately, since the goal is to select the most probable internal states given specific sensory observations it’s possible to ignore the denominator since it’s just a normalization term and so doesn’t change where the peak posterior probability is found. This technique is known as maximum likelihood estimation (MLE), which essentially means picking the internal states that maximize the value of the numerator of Bayes theorem. Because the numerator is equivalent to a joint probability distribution, performing MLE corresponds to picking the internal states that maximize the joint probability of sensory observations and the model of their causes:

Statistical models of joint probability distributions are also known as generative models - this is what the “generative” in “generative pre-trained transformer (GPT)” and other generative AI models refers to. Generative models have the useful property that they can produce, or generate, samples of the data they model; just as ChatGPT generates the most likely words to complete a snippet of text, an organism’s model of its environment is trained to generate the next most likely sensations. This ties into theories of predictive coding in the brain, which posit that the brain compares predicted stimuli to real observations to evaluate the accuracy of its models. LLMs are evaluated in a similar way by comparing predicted continuation words to the true continuation and adjusting model weights as needed to improve accuracy.

Computing the joint probability requires organism to answer two questions:12

- How likely are these sensory observations given my internal states?

- How likely (i.e. plausible) are my internal states in general?

The first question is straightforward. If we think of internal states as a mathematical function that computes the probability distribution of sensory observations, plugging in the values of the internal states directly outputs the distribution \(\small P(\text{Observations} \vert \text{Internal states})\). By comparing the predictions of the model to the observed sensory data the organism can evaluate its performance, and the degree of error indicates the magnitude of updating that’s required. If the current model assigns a low probability to the true sensory observations it probably isn’t a very good model.

The second question requires a more nuanced treatment. The surface level answer is that the most probable value of \(\small P(\text{Internal States})\) is the one that best explains historical observations (i.e. the results of prior training), but this doesn’t help determine how organisms should select the early values of the prior before much (or any) data has been observed.

The trick is to realize that the most probable model is the simplest one that explains the data, and that organisms should therefore have a bias towards simple configurations of internal states. This is a principle commonly known as Occam’s razor and formalized in Solomonoff’s theory of inductive inference.

To build intuition for this principle, imagine you were tasked with randomly generating every possible model that could generate some observed data by following this process:

- Flip a coin

- Note down 1 for heads and 0 for tails

- Check if a Turing machine (i.e. a computer) running the models encoded by every subsequence of the binary string is able to reproduce the observed data, and add all the successful strings to a list (including duplicates)

- Go back to step 1 and repeat the process, appending the next coin flip result to the binary string

If you looped through this process for an infinite amount of time you’d have a long list of every model capable of reproducing the observed data. What you would then find is that the models described by shorter binary strings occurred much more frequently in your dataset than longer (more complex) models, because shorter strings require fewer steps to generate and so are more probable; in mathematical terms, the probability of generating a specific binary string of a particular length is given by \(\small \frac{1}{2^{\text{length}}}\).

Of course, no organism is literally calculating the probability of every possible model to inform their prior - this is clearly infeasible. What they are plausibly doing however is randomly sampling from the distribution of models, keeping those that work, and pruning the ones that don’t. Because shorter models are more likely to be generated, this random sampling biases towards shorter and simpler models. Another nice property of simpler models from the perspective of an organism is that they require fewer resources to encode, so biological systems like neurons that actively try to maximize their energetic efficiency have an inbuilt bias towards simpler representations.

A further idea drawn from Karl Friston’s theory of active inference is that organisms have a preferred set of internal states determined by evolution. Rather than just updating their models to better fit their environments, active inference suggests that organisms also shape their environments to better fit the internal states. In this sense, the most probable internal states are those which the organism wants to happen and will take action to make happen.

So when it comes to selecting the prior \(\small P(\text{Internal States})\), the probability is likely to be a mélange of evolutionarily ingrained preferences, model complexity, and the results of prior inference steps.

After the most likely model has been determined, it can be adopted as a new prior and fed into future calculations. By iteratively updating their internal states to better match sensory observations organisms gradually improve their generative model of the states of their environment and resultant sensations.

I suspect that this iterative model updating has a fundamental link to intelligence, and so now we’re finally ready to attempt a definition:

Intelligence is a measure of how efficiently a system uses information from observations to build generalizable predictive models of its environment

What do I mean by efficiency? Of course we can’t just simply measure how fast an organism learns in some random context and call that efficiency because some things are easier to learn that others. So we need to try and account for the amount of information that is actually useful in an environment. In an intuitive sense it’s not informative to be told things you already know, so perhaps we can construct an formula like this:

A potential way to express this mathematically using concepts from information theory could be the following:

- \(\small \text{Observed information}\) is simply the information entropy of sensory observations. However, because this is meant to represent the real observations rather than the distribution of all possible observations, I’ve added a little \(\small \tau\) symbol to indicate that these are the probability distribution of observations conditioned on the true hidden environmental states: \(\small P(\text{Observations}_\tau) = P(\text{Observations} \vert \text{True hidden environmental states})\)

- \(\small \text{Known information}\) can be derived from the entropy of the predicted observations given the current internal states. If the observations are predicted perfectly (i.e. the predicted distribution equals the true distribution), they are essentially already known and so the information content would be the same as the unconditioned observations

In terms of information entropy (\(\small H\)), which has the formula:

We get the following construct:

Which is actually the definition of mutual information: \(\small I(\text{Observations}_\tau\text{, Internal states})\). If the observed and known information is equal (i.e. the mutual information is 0) it means that a new observation tells the organism nothing new about the states of its environment. This implies that if the organism’s model of its environment is perfect, there’s no need to make any observations anymore. From the perspective of the organism, this is a nice place to be because you don’t have to spend energy collecting myriad sensory observations and can just run off your internal simulation of the world.

If the amount of information that could possibly be learnt from a sample is the non-redundant information, we might suppose that a particular organism could capture anywhere from 0 to 100% of that information to train its internal model. So I could hypothesize that the amount that is learned at a given level of model accuracy is given by the below equation, where \(\small g\) is a measure of intelligence:

This formula is similar to Newton’s law of cooling, which states that “The rate of heat loss of a body is directly proportional to the difference in the temperatures between the body and its environment”. This learning rate equation suggests a statement like “The rate of learning is directly proportional to the accuracy of an organism’s model of its environment”. I don’t know if this comparison is actually valid, but it seems like an interesting analogy and there’s a long history of links between information theory and thermodynamics13. This would imply that intelligence is analogous to the heat transfer coefficient, in other words, it’s a variable which determines how quickly information is conducted away from a system during the learning process (or a knowledge acquisition rate).

Similarly to Newton’s cooling law, this equation can be reformulated as an exponential function that shows the amount of information learned over time:

And expressed in terms of the amount left to learn:

Lastly, we should consider that the environment may generate information that is unobservable because the organism’s sensors aren’t equipped to detect it. This sets an upper bound on the amount of information that can be learned about any given environment. Adding in the unobservable information we get the following equation:

Which says, the amount of information learned about an environment depends on how much information is contained in observations and the learning rate \(\small g\) (intelligence), with an upper bound determined by information that is produced by an environment but can’t be learned because it’s inaccessible. Equations of this form look like this:

`

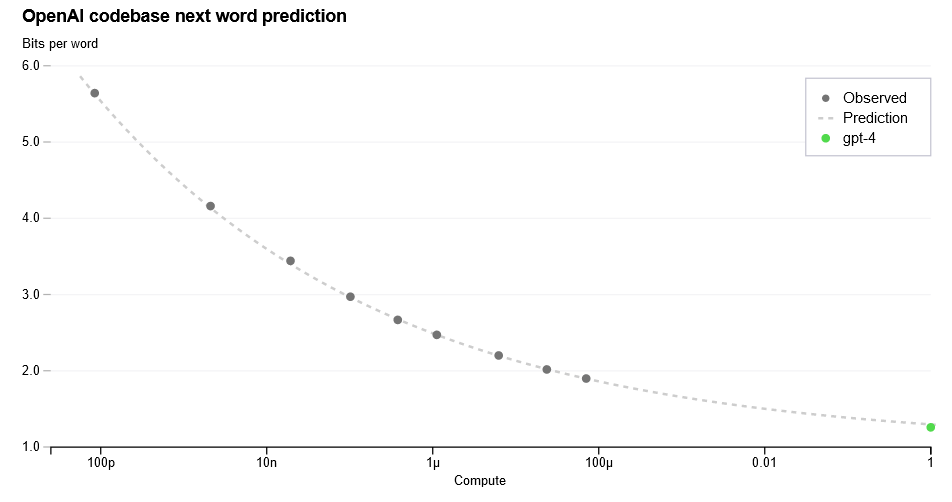

Human learning curves have shapes much like these, with rapid initial learning before gradual slowing and plateauing. Machine learning loss curves also often (but not always) fit well to similar functions of the following form where \(\small n\) is some measure of compute/samples seen:14

Which you can see in this example from OpenAI’s GPT-4 paper.

This formalism is a way of thinking about intelligence as a measure of how effectively systems make use of useful information. More intelligent systems can extract more signal per observation, and take less time to learn the same models. More intelligent systems should also be able to learn effectively in noisy environments, while less intelligent agents may require high-signal environments to functionally extract signal (or many repetitions)15.

Knowledge, in contrast to intelligence, seems more aptly to be a measure of how good one system’s model is of another. There’s a nice way to measure this using the Kullback-Leibler (KL) divergence, a common way to evaluate the closeness of two distributions. It’s a measure of distance16 where the units are information; it tells you how many bits of information are required to distort one distribution into another17. Another way of interpreting it is the expected excess surprise from using one distribution \(\small P(x)\) as a model of another \(\small Q(x)\), or the information that you lose by using one distribution to approximate another.

Yet another way of interpreting the KL divergence is as the number of extra bits per message required to encode information about events drawn from the true distribution using the model distribution18. If you substitute \(\small Q(x)\) for the real hidden environmental states, and \(\small P(x)\) for the organism’s internal states (model), then by improving its model of the world the organism is indirectly minimizing the KL divergence19. This ties into a bioenergetic reason for why brains would like to minimize the KL divergence; better models reduce the amount of information required to model the true state of the world because organisms are not wasting energy to encode and transmit redundant or useless non-predictive information.

Organisms naturally compress reality by modelling it, which seems to be a defining behaviour of all living systems. If an organism is fed a constant stream of sensory data and it tries to build a model that efficiently predicts future data, it is necessarily performing a compression. Just like there is a fundamental link between intelligence and prediction, there is a fundamental link between those concepts and compression too. Since compression entails representing the causes of sensory data in terms of more fundamental hidden states it is analogous to understanding the causes of those states, because fundamental patterns have to be recognized in order to be able to compress them.

Biological versus machine intelligence

So far I’ve been using the word organism and have written mainly in reference to biological intelligences. But what I want to suggest is that all intelligent systems basically follow the same principles - replace organism with artificial intelligence in the previous section and it doesn’t change the overarching framework. You can even go one level more abstract and replace the environment with a generic system, such that intelligence is just a rate at which one system learns about another. Under the hood, every learning system is just building models and testing them against observations20.

Many people have noted that deep learning systems seem to have more in common with biological systems than standard algorithms. Algorithms like linear regression may be highly “intelligent” under low noise domains and simple problems, but they are brittle. LLMs have more in common with biological intelligence in that they are more general, but more error prone and fuzzy. Making mistakes is necessary price to pay for generalizability21. Without an inductive bias - a prior - there are infinite ways to fit models to data and no particular reason to select one or the other22.

Organisms and machine learning systems both do something that can be abstracted as fitting internal models to unknown true causes that underlie observations. Deep neural networks are universal function approximators, which boils down to the capability to create polynomial regressions that can fit any arbitrary function23. If artificial neural nets can do this, biological brains - which are more complex - should be similarly capable of approximating any function. While the universal approximation theorem proves that a single layer neural network can learn anything, it does not specify how easy it will be for that neural network to actually learn something. If it’s true that biological and machine intelligences are mathematically similar behind the scenes, where do they differ?

It still takes a huge amount of samples and compute for transformers to learn the underlying structure of language relative to a human. LLMs may be extremely knowledgeable, but they are much less efficient (intelligent) learners than people. I suspect this difference in machine vs. human capabilities results mainly from the richness of the input space and the efficiency of the hardware and algorithms.

Learning systems are mirrors of their environment, and systems cannot bootstrap themselves to learn about anything without connection to an external environment, no matter how intelligent they are. There needs to be something to learn and predict; what any system can possibly learn is limited by the information it is fed. The type of inputs fed to a given system define its representation space and learning capacity, which for us includes the basic sense data we perceive as colour, smell, taste, sounds, and so on. For an AI system, these fundamental representation units will be the format of the training and input data, such as word tokens for a language model. Everything that is learned by any system is represented eventually in terms of these fundamental units - these are their bridges to the true structure of reality.

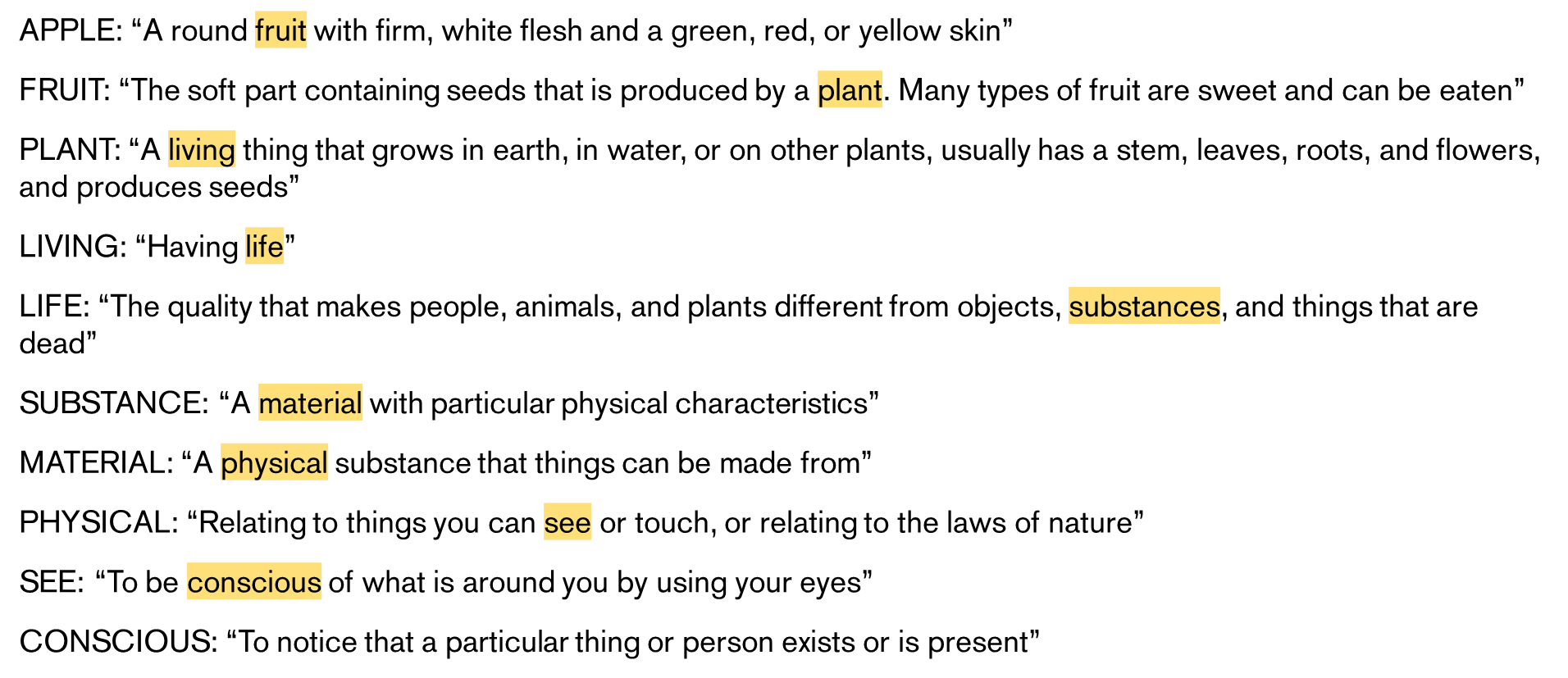

As a neat example of how foundational the concepts of consciousness and sensory perception is to human understanding, if you go onto Wikipedia and traverse it by clicking on the first link of every page you will almost always pass through articles on consciousness, existence, object qualities, or philosophy24. Similarly, if you recurse sufficiently many times through definitions in a dictionary you’ll end up in the same set of fundamental irreducible concepts - here’s an example from the Cambridge dictionary:

While we live in a sensory word, and so relate every concept we understand ultimately to sensations, ChatGPT lives in a text world, so it has to relate everything to text. For ChatGPT text is fundamental, but this means it’s untethered from the real world. There’s still enough latent information about the true states of our world in text for ChatGPT to learn a decent world model, but it’s presumably missing out on a lot of information about the world that we take for granted. The composition of the environment imposes fundamental limits on knowledge, and our conscious experience can only be as rich as the environment we exist in. It’s likely that the reason that LLMs are so good at coding relative to other tasks is because the domain of programming can be almost entirely represented in data that LLMs can access and take as input, while the domains of other tasks are largely offline. We probably won’t think that AI can “understand” the world until it has a similar input space to ours, because how we understand the world is through the components of conscious experience.

With that out of the way, on to hardware.

Implementing intelligence

If we accept that intelligence is a property that things have in different degrees, a natural follow-up question is then: what makes something more, or less, intelligent than some other thing?

It turns out that if we construct many different plausible tests of intelligence - vocabulary, arithmetic, shape rotation, reaction speed, whatever - and test people on them, performance on any one test will be positively correlated with performance on every other test. People who do well on one type of cognitive test tend to do well on all types of cognitive tests, and vice versa. This is one of the most consistently replicated findings in psychology, known among intelligence researchers as the positive manifold25. The existence of a positive manifold means we can statistically extract a single latent variable - the g factor - that accounts for 40-50% of the variance in performance on intelligence tests.

The emergence of a g factor from test data suggests that there is some unitary ability that enables people to perform well on all types of cognitive tests. This lines up with our common notion of intelligence as a broad cognitive capability, so g is often taken as a proxy for general intelligence26, and I will also use intelligence, g, and intelligence test performance interchangeably. There are of course other things beyond g that matter for test taking: practice, domain knowledge, language familiarity, concentration, motivation, socioeconomic status, and so on, yet g can always be found to explain some portion of test performance. Different cognitive tasks may draw on different abilities, but they all draw on g.

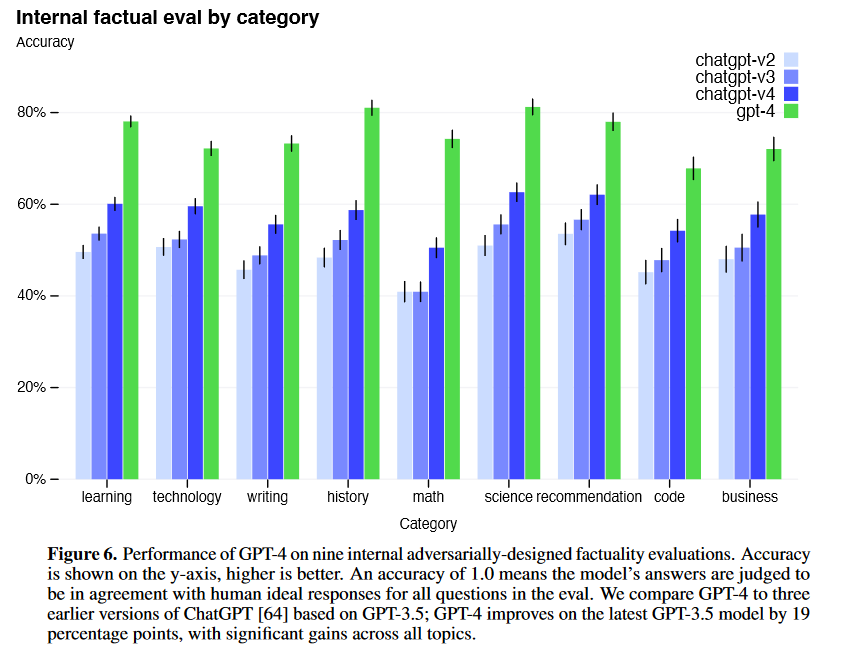

The positive manifold doesn’t seem to be unique to humans either. Evidence of a general factor of intelligence has also been observed in non-human animals, such as primates, dogs, and mice - although the evidence is only weakly positive27. Large language models also seem to exhibit a positive manifold; the below graph from OpenAI shows that newer versions of GPT models exhibit positive performance correlations across distinct evaluation tasks28.

Despite g’s apparent simplicity as a statistical construct, the underlying determinants of human intelligence are multifaceted and difficult to pin down. Intelligence is partly heritable, implying that it is to some extent determined by inborn structural, genetic, and/or neurochemical factors. The precise degree of hereditability is controversial. Twin and family studies have historically suggested that genetics accounts for ~50% of the variation in performance on intelligence tests in typical environments (20-30% in children and up to 70% in adults)29. Other methods in the genome-wide complex trait analysis (GCTA) family that assess correlations between intelligence and genotype in unrelated individuals tend to produce lower hereditability estimates of 20-30%29. Despite this purported high heritability, the polygenicity of intelligence makes it challenging to identify “intelligence genes”29; any individual gene variant is likely to have a miniscule effect on someone’s overall intelligence, and it seems likely that intelligence is influenced by the aggregate contributions of tens of thousands of gene variants. Polygenic tests are poor predictors of individual intelligence today - only able to account for 1-5% of the variation in intelligence3031 - presumably because we have yet to identify and incorporate the long tail of genetic variants with tiny effect sizes. It may also be the case that studies on the heritability of intelligence (especially twin and family studies) are overestimating the genetic contribution due to methodological flaws, contributions of shared environment, and/or assortative mating32.

At the level of individual genes, we know from genome-wide association studies (GWAS) that genetic variants associated with intelligence test scores tend to be related to neurogenesis and the cell cycle, the synapse, neurite growth and the cytoskeleton, calcium signalling, and the NMDA-receptor29. GWAS doesn’t necessarily identify the most important genes for a given trait as those are likely to be under heavy selection pressure and therefore intolerant of variance, but it does give some insight into the types of genes that contribute to a trait at the margins. To give a sense of the broad range of functions of genes involved in intelligence I have reproduced ten of the top corroborated hits from a large 2018 GWAS study on intelligence in the table below33.

| Gene symbol | Protein name | Potential function |

|---|---|---|

| BSN | Bassoon presynaptic cytomatrix protein | Involved in scaffolding and neurotransmitter release around the presynaptic active zone34 |

| RBM5 | RNA-binding motif protein 5 | Component of the spliceosome, involved in apoptosis and cell cycle arrest35 |

| APEH | Acylpeptide hydrolase | Enzyme that hydrolyzes acetylated peptides/proteins, may be involved in destroying oxidatively damaged proteins36 |

| CAMKV | CaM kinase like vesicle associated protein | Binds calmodulin, localizes in synapse active zones37. Maintains dendritic spines38 |

| RHOA | Ras homolog family member A | Small GTPase that regulates remodeling of the actin cytoskeleton, involved in dendritic arbor growth39 |

| NEGR1 | Neuronal growth regulator 1 | Involved in neurite outgrowth40 |

| EXOC4 | Exocyst complex component SEC8 | Involved in vesicle trafficking at synapses41 |

| CSE1L | Cellular apoptosis susceptibility protein | Involved in apoptosis and the cell cycle42 |

| NICN1 | Nicolin 1 | Unclear |

| STAU1 | Double-stranded RNA-binding protein Staufen homolog 1 | Involved in transporting mRNA to the site of translation along cytoskeletal networks, as well as mRNA degradation43 |

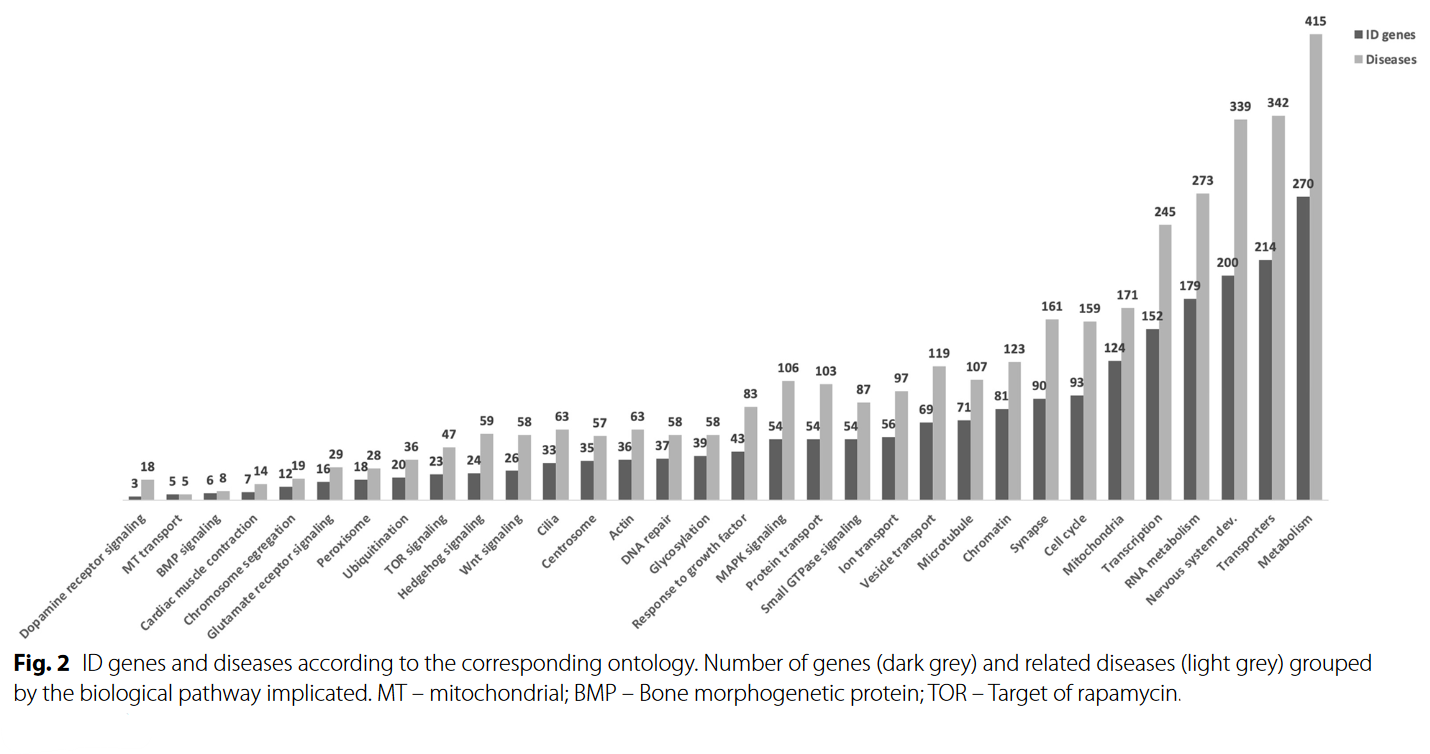

Other intelligence GWAS have also implicated the plexin44 and netrin family of proteins, which are involved in guiding neurite growth cones to form new synaptic connections. GWAS are too blunt of a tool to allow for definitive conclusions (and it’s entirely possible that the results are dominated by spurious hits as many historical intelligence GWAS have failed to replicate), but they do seem to suggest that intelligence is affected by a diverse set of neuronal parameters: absolute number, efficiency, connections, integrity, and structure. Backing this up, the causes of intellectual disability are similarly heterogenous; as shown in the below graph, genes associated with intellectual disability span a large range of functions impacting metabolism, cytoskeleton, neurodevelopment, and synaptic function4546.

If there’s any one takeaway from genetic studies it’s that there’s no single simple tuneable parameter that determines intelligence - the functions of intelligence genes are global in nature. This seems consistent with high intelligence being a consequence of good global brain function downstream of favourable genetics and environment. Many little things need to go right for high intelligence, and one or two big problems can undo these small positive aggregate contributions.

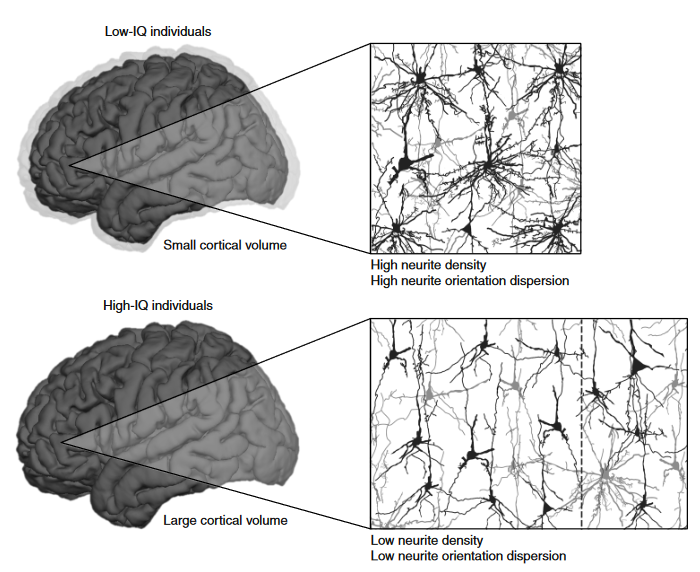

Zooming up to the macrostructure level, brain volume has reliably been found to correlate with intelligence test scores at around r=0.347. Both white and grey matter volume correlate with intelligence, although grey matter perhaps to a slightly greater degree48. While the volume and/or thickness of specific subregions including the frontal, parietal, and temporal cortices and the hippocampus also correlate with intelligence, no specific structural element correlates much above r=0.3, and most are lower48. Apart from volume, highly intelligent individuals tend to have more, better organized, neurons - as depicted in the image below.

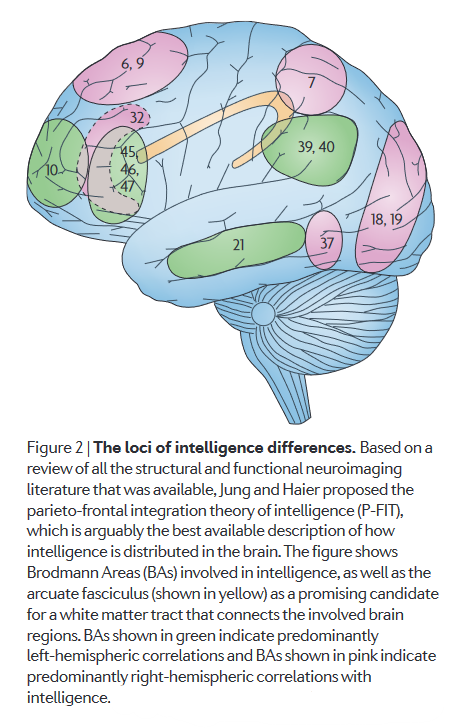

Intelligent brains are more efficient consumers of energetic resources4950, and are more sparingly organised51. Energetic efficiency has close links to intelligence: learning disabilities and low IQ scores are common features of mitochondrial disorders, and brain activity seems to be elevated in people with Down’s syndrome compared to healthy controls49. Brain energy/glucose consumption is elevated when people learn new tasks and gradually decreases with practice. People with higher intelligence test scores tend to show larger decreases in task-specific brain activity with practice, i.e. they have greater efficiency gains49. Connection efficiency and white matter integrity also plays a role in intelligence, particularly within and between the regions implicated in the parieto-frontal integration theory (P-FIT), shown below48.

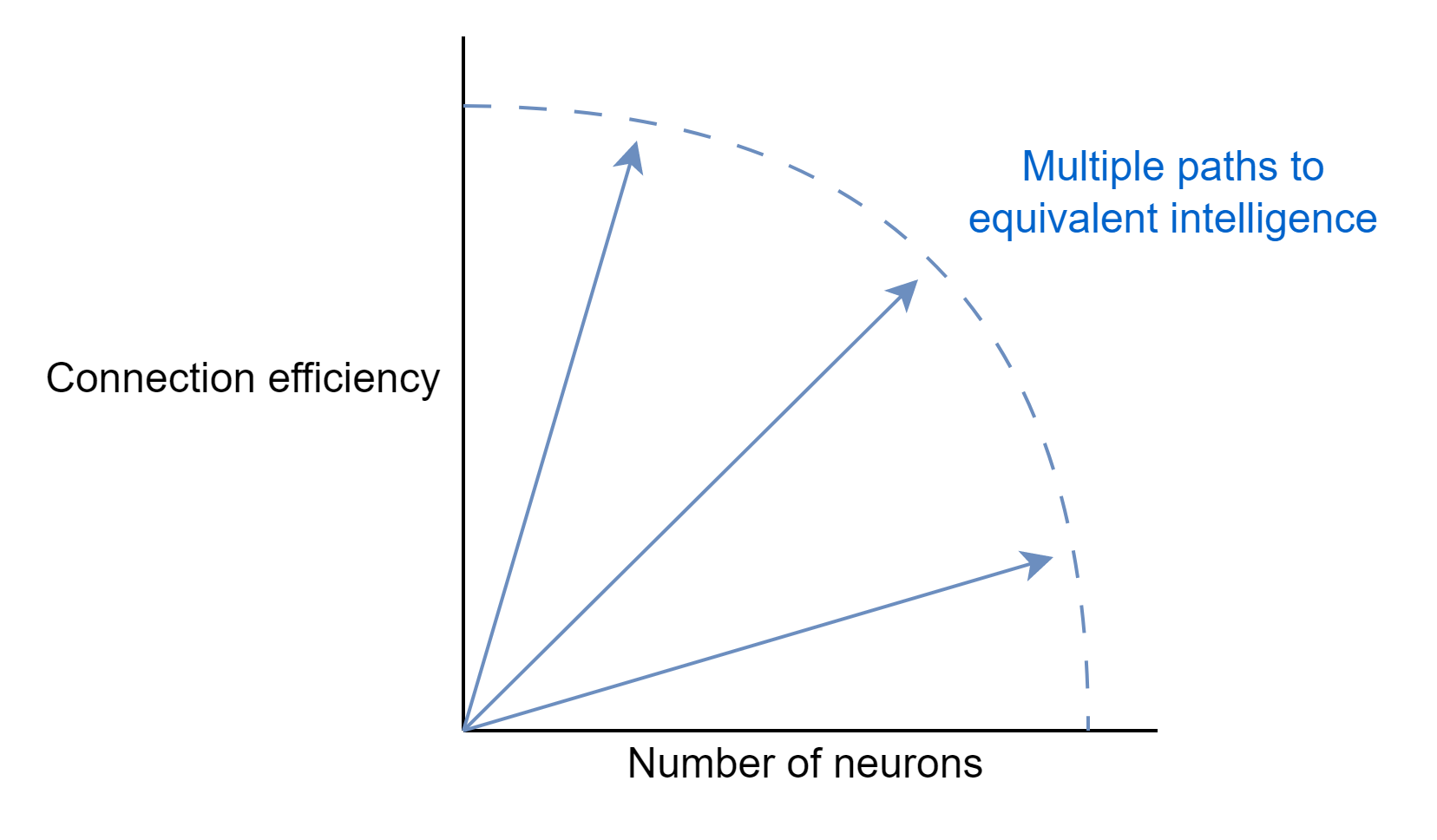

An important caveat is that just because these correlations exist in large samples doesn’t mean that they tell you much about someone’s intelligence at an individual level. For example, men and women have equivalent average intelligence test scores52 even though men tend to have larger brains (controlling for larger body size)25. The correlation of architectural or genetic factors with intelligence is low, and any one factor only explains a single digit percentage point of the variance in intelligence, or less. There appear to be multiple ways of constructing an intelligent brain, although ultimately they do seem to boil down to increasing neuron count and/or connection speed/efficiency.

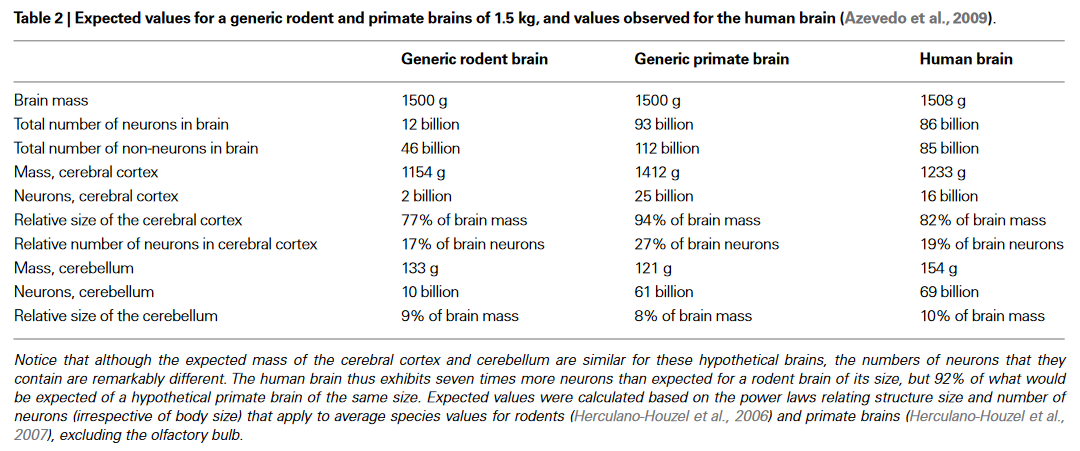

Looking beyond humans, many of the associations seen in human brains between scale, efficiency, and intelligence seem to hold broadly across the animal kingdom. We know human brains are nothing special architecturally, they are linearly scaled up primate brains5354. Take an average primate brain, scale it up to human size, and you get a brain that’s roughly comparable to the human one in terms of mass and number of neurons, as shown in the below table.

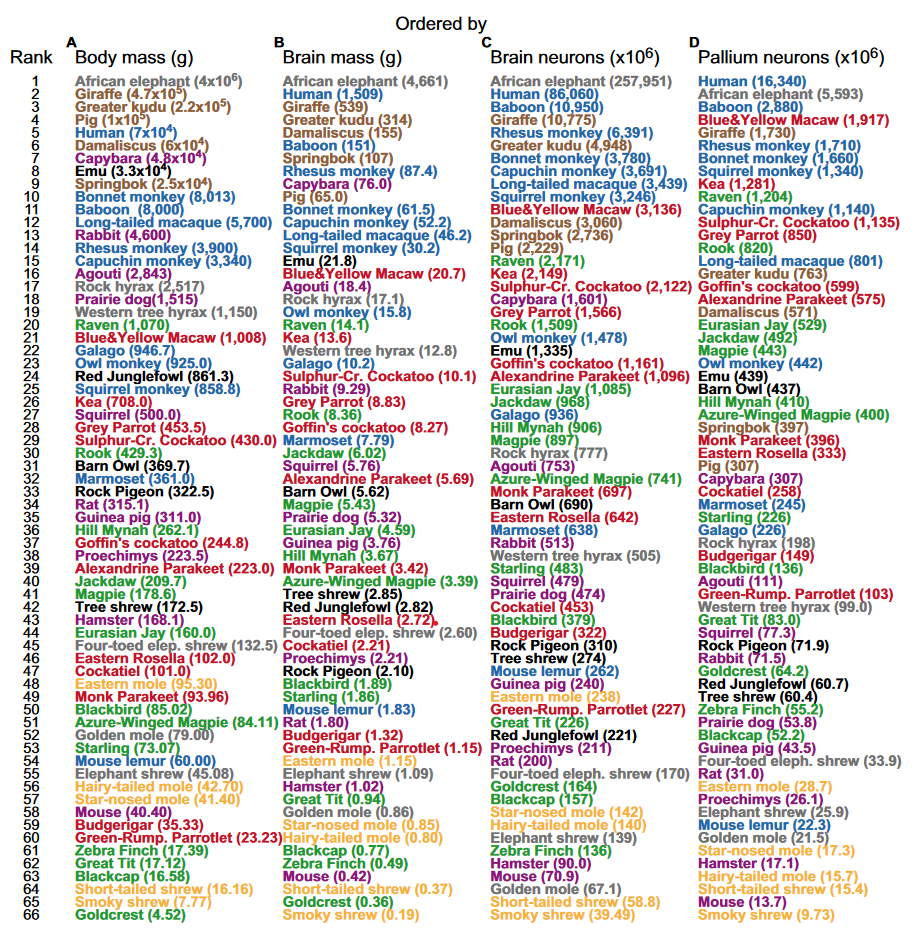

Yet brain mass - whether absolute or relative to body size - is a flawed metric, as what really seems to matter is the number of neurons in the pallium (essentially the cerebral cortex). Our subjective impression of what animals are intelligent correlates well with the number of pallial neurons55.

On this metric, birds perform quite well despite their small brains. Just as a human brain is a scaled up generic primate brain, so is a corvid’s brain a scaled-up songbird brain56. Birds have a somewhat different brain architecture to mammals, with greater neuron packing and a relatively higher number of neurons in the pallium which compensates for their smaller absolute size56. As with other animals, birds’ cognitive task performance does seem to scale with cortical (pallium) neurons57.

The same traits that influence the variation in intelligence among humans also seem to influence the variation in intelligence among animals, as one paper concludes:

“The best fit between brain traits and degrees of intelligence among mammals is reached by a combination of the number of cortical neurons, neuron packing density, interneuronal distance and axonal conduction velocity—factors that determine general information processing capacity (IPC), as reflected by general intelligence.”58

This echoes what I said above about the human brain, with intelligence mostly determined by a two factor model of cortical neuron number and connection efficiency. The more neurons, the more concepts a brain can encode. The more efficient, the faster a brain can retrieve and encode new concepts, and integrate across functional regions. There are multiple paths to high intelligence, and space constraints may force some animals down the route of optimising for efficiency.

I’ve focused on brains in this section, but I don’t want to imply that brains are the only architecture capable of exhibiting intelligence. Biology may have settled on brains and neurons as the preferred substrate to enable within-lifetime learning, but across-lifetime learning using DNA as a substrate is perhaps more important. Computation is done by the body too, and evolution is the mechanism by which bodies come to better model their expected environment. We should expect some trade-off between an organism’s environmental complexity or variability, lifespan, and their investment in brains. Fecund organisms with short lifespans and high mutation rates don’t necessarily need to invest in brains as their rapid cycling through generations allows their genetics to adapt quickly to environmental change. Static organisms, like plants, can do without brains entirely since they are rooted in place and have no need to range around variable environments.

The patterns seen in biological intelligence have parallels in machine intelligence as well. The bitter lesson of AI research has been that methods leveraging increased computation have had the most success. Increasing computation and scale improves performance, with no as of yet upper bound59. Large parameter deep learning models perform better on evaluation metrics and learn faster than smaller models with the same architecture59. That being said, there is a trade-off; large models are expensive to train, and for a fixed amount of compute it is often better to train a smaller model for longer6061.

Bigger deep learning models can also abruptly develop entirely new capabilities that the smaller ones lack - this is commonly referred to as emergence.

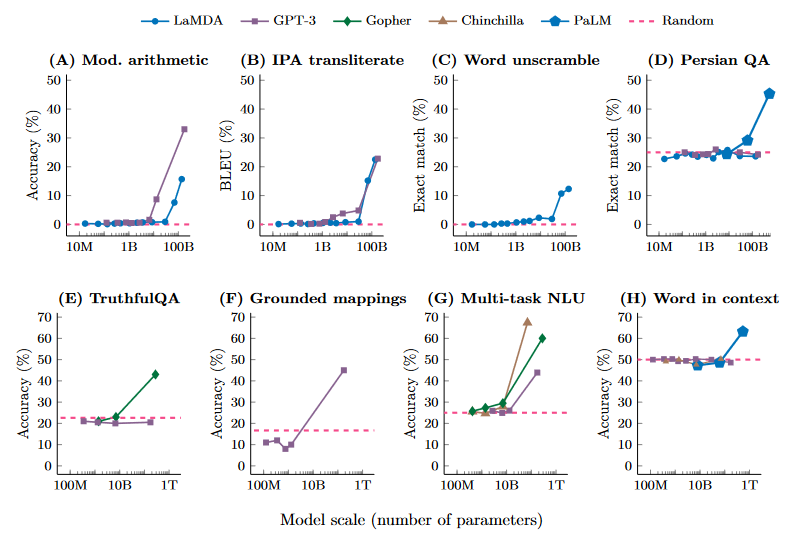

Eight examples of emergence in the few-shot prompting setting are shown in the below graphs. These examples show that various language models perform randomly until a certain scale, after which performance suddenly increases to well-above random. We see discontinuous jumps in the abilities of large language models. Jason Wei has documented more than 100 further examples of emergence on his blog here. We may be surprised by the emergent capabilities of language models, but perhaps we shouldn’t be: after all, language was a sudden emergent ability in humans that seems to have more to do with scale than an architectural innovation.

Emergence has been criticised as an illusion that results from the choice of binary true/false evaluation metrics that don’t award partial credit, when in reality the model smoothly improves with scale under more granular metrics62. Jason Wei addresses this and some of the other common criticisms of emergence here if you’re interested. Even though the sharpness of transitions is a matter of debate, what is trivially true is that larger deep learning models are more capable than smaller ones , which is related to the concept of phase transitions.

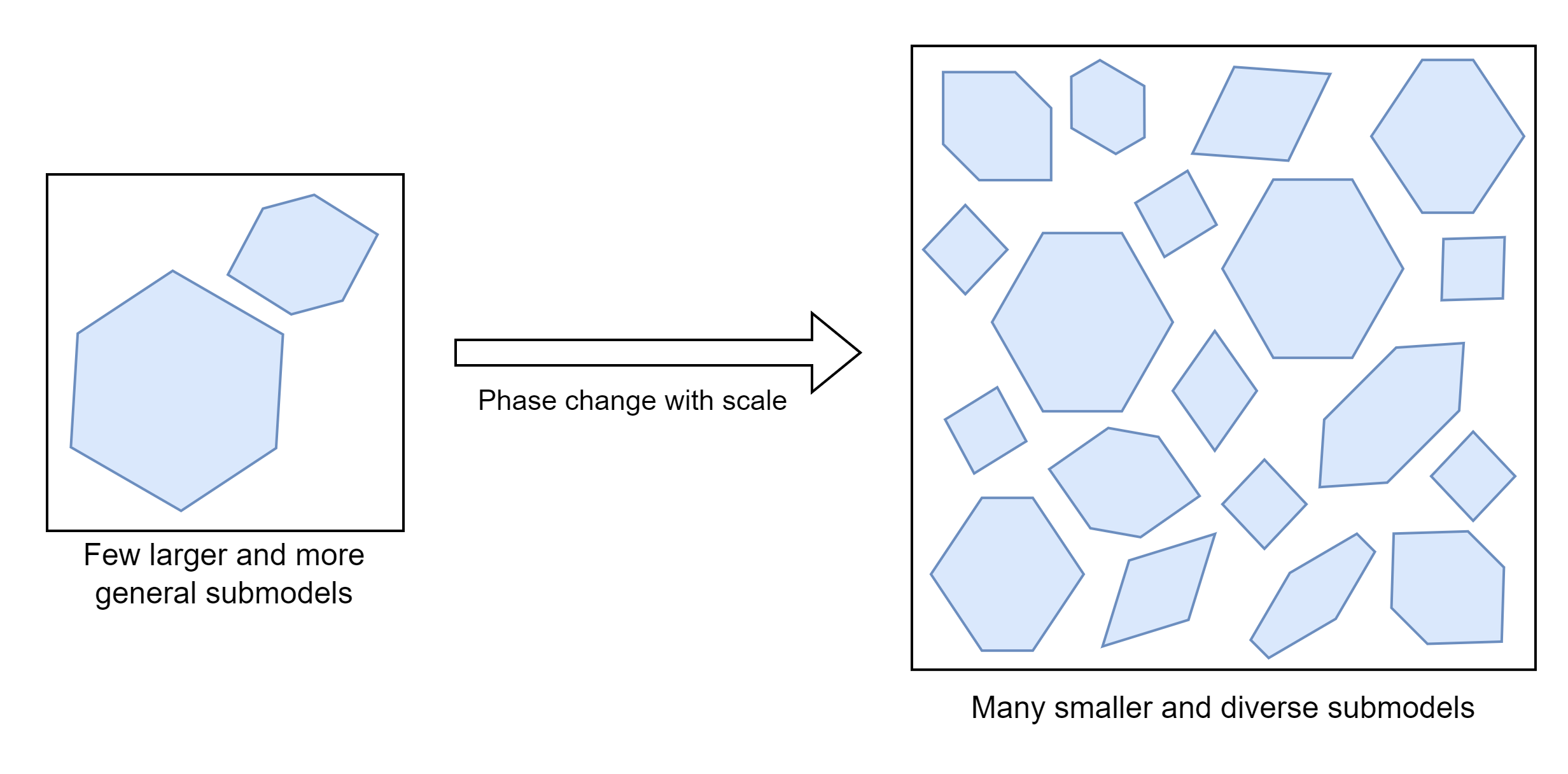

Phase transitions are when the properties of a system change without the actual composition changing, such as when water freezes63. When you change the organisation of a system, new and different behaviours can emerge. Large systems are more likely to exhibit emergent properties because there are combinatorically many more ways of arranging systems with more components64. In intelligent systems this might manifest in the fracture of big general models into more refined submodels that better fit sections of the data65. This fracturing plus some connection length penalty seems likely to be related to why brains have ended up being organised into distinct functional regions66.

In some cases learning curves are not well behaved and follow a U-shape in which error rates worsen before eventually improving. This blog post has some good examples of these behaviours in machines and humans. U-shaped learning and “Grokking”67 - when neural networks overfit and perform poorly for a long time before generalizing - seems to have a close relationship with phase changes68. In complex or noisy domains learning systems are likely to be fooled by randomness for a time leading them to create models that overparameterize the observational data, essentially memorizing it, before eventually developing a deeper and more general understanding.

In conclusion

If you buy into the arguments I laid out, that means you accept that there’s nothing really special about human intelligence. My hypothesis is that intelligence is at its core an efficiency measure: how many computational steps at what cost does it take to derive a generative model of some observational data? Further, I’ve suggested that the intelligence of a system is mainly determined by the amount of its computational units multiplied by its ability to efficiently marshal those units for inference. Smarter agents are those that can sample the space of possible models more broadly and efficiently, and more rapidly validate them against observations69.

Making more capable and intelligent AIs will probably involve some combination of architectural and hardware innovations, as well as broadening the input space (multimodality). On some metrics, there still seems to be a long way to go before AI systems can match biological brains. With ~16 billion cortical neurons, and 1,000 to 10,000 synapses per neuron, you could argue that humans have roughly 16-160 trillion model “parameters” in the cerebral cortex70 versus hundreds of billions for the latest deep learning models. Current deep learning algorithms (especially backpropagation) are wildly inefficient compared to the energy consumption performance achieved by biological neurons. We’ll probably close the gap eventually, but compute hardware is already a scarce resource.

In the meantime, we may see a shift towards smaller, more focused models. We should expect evolution to select for brains that have parameter statistics that mirror local environmental complexity71. Similarly, it would seem to make sense to design machine learning models with a scale proportional to the complexity of their input space. Feeding in carefully curated high information content data is another way to potentially train more capable AI models without requiring algorithmic breakthroughs or additional compute resources. Allowing AI models to select their own inputs, rather than making the choice for them might be another interesting avenue to explore.

When it comes to making AI safer, it’s plausibly dangerous to let these systems have access to too much information about the world before we know how they will use that information. By limiting the amount of information AI systems have access to and/or their multimodality it might be possible to still test and improve their intelligence while keeping their knowledge of the world limited. Even the most superintelligent AI shouldn’t be able to pose much of a threat without deep knowledge of its environment and the ability to interact with it broadly, since the problem of induction implies that they can’t just figure everything out logically. Additionally, per the theory of active inference, finding ways to encode favourable priors into agentic AIs could help encourage them to take actions to shape the world positively.

-

Gottfredson (1994) Mainstream Science on Intelligence: An Editorial With 52 Signatories, History, and Bibliography ↩

-

Legg et al. (2007) Universal Intelligence: A Definition of Machine Intelligence ↩

-

This and following sections draw heavily from Karl Friston’s free energy principle and theory of active inference, for a review of the principle see here ↩

-

This actor/sensor boundary is an example of what Karl Friston refers to as a Markov blanket, a term inherited from Judea Pearl’s causal statistics. Markov blankets have a mathematical definition as statistical partitions in Bayesian network graphs, but Friston uses the term more loosely to refer to the outer layers of organisms (or nervous systems) that interface directly with the environment. A Markov blanket in the Fristonian sense is a sort of information chokepoint, filter, or portcullis; all information that comes in or out of an organism must pass through its Markov blanket, and any information that doesn’t make it through is lost behind a veil of ignorance. In the diagram, the sensors and actors form the Markov blanket of the internal states ↩

-

The “environment” is anything outside of the information processing parts of the organism, which may also include the organism’s body as well as the surrounding world ↩

-

A quote attributed to William James ↩

-

Complexity often emerges from simple rules; one of my favourite examples of this principle is Conway’s game of life. ↩

-

Also known as a world model ↩

-

Stephen Wolfram has a nice explanatory section on what models are in his long post on how ChatGPT works (CTRL+F “What is a Model?”) ↩

-

Albert (2011) What’s on the mind of a jellyfish? A review of behavioural observations on Aurelia sp. jellyfish ↩

-

The Art of Statistics by David Spiegelhalter ↩

-

Note that I’m not suggesting these are consciously calculated, but that they are implicitly answered by the organism’s information processing units (e.g. neurons) ↩

-

Viering et al. (2021) The Shape of Learning Curves: a Review ↩

-

Noise probably imposes fundamental limits to the rate at which information can be learned about a system, no matter how intelligent the agent doing the learning. If there’s too much noise, it could even be impossible to learn the true underlying function of an environment, because some false model will be likely to better fit observed data than the true model. See https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-023-36657-z ↩

-

Technically KL divergence is not a true measure of distance, because it’s not equivalent (symmetric) backwards and forwards ↩

-

A Beginner’s Guide to Variational Methods: Mean-Field Approximation by Eric Jang ↩

-

Stack Exchange - Why do we use Kullback-Leibler divergence rather than cross entropy in the t-SNE objective function? ↩

-

Karl Friston claims that organisms are performing variational approximate inference, by indirectly minimizing the KL divergence in a similar manner to the calculation of the evidence lower bound in machine learning. Even if organisms are not literally performing the calculation, the claim of the free energy principle is that organisms are doing something mathematically equivalent to variational Bayesian inference anyway. See this paper for further details: https://arxiv.org/abs/2205.11543 ↩

-

See: All Life is Problem Solving by Karl Popper ↩

-

What Makes Us Smart by Samuel Gershman ↩

-

Cheng et al. (2018) Polynomial Regression As an Alternative to Neural Nets ↩

-

Ibrahim et al. (2016) Connecting every bit of knowledge: The structure of Wikipedia’s First Link Network ↩

-

g is what IQ tests aim to measure, although the IQ score itself represents test scores fit to a normal distribution and the absolute value doesn’t have meaning as a quantification of “level of intelligence”, but rather reflects deviation from the average score (set to 100). IQ tests are usually made up of a variety of test types and bias towards tests that are better correlated with g (i.e. have “high g loading”) ↩

-

Poirier et al. (2020) How general is cognitive ability in non-human animals? A meta-analytical and multi-level reanalysis approach ↩

-

This is not true for every single task. The inverse scaling prize was an interesting competition that was run to find examples of tasks that models performed worse at as they increased in size, I don’t think this invalidates the existence of a positive manifold, especially as the very latest models like GPT-4 have reversed the trend and do well on most of these tasks now - but it is an interesting feature of LLMs. AI models can seem superhumanly intelligent in some tasks and extremely dumb in others, while people usually seem to be more balanced in their cognitive capabilities ↩

-

Deary et al. (2021) Genetic variation, brain, and intelligence differences ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4

-

Genç et al. (2021) Polygenic Scores for Cognitive Abilities and Their Association with Different Aspects of General Intelligence-A Deep Phenotyping Approach ↩

-

Border et al. (2022) Assortative mating biases marker-based heritability estimators ↩

-

Savage et al. (2018) Genome-wide association meta-analysis in 269,867 individuals identifies new genetic and functional links to intelligence ↩

-

Liang et al. (2016) The pseudokinase CaMKv is required for the activity-dependent maintenance of dendritic spines ↩

-

Singh et al. (2019) Neural cell adhesion molecule Negr1 deficiency in mouse results in structural brain endophenotypes and behavioral deviations related to psychiatric disorders ↩

-

OMIM - STAUFEN DOUBLE-STRANDED RNA-BINDING PROTEIN 1; STAU1 ↩

-

Zabaneh et al. (2017) A genome-wide association study for extremely high intelligence ↩

-

Maia et al. (2021) Intellectual disability genomics: current state, pitfalls and future challenges ↩

-

Cox et al. (2019) Structural brain imaging correlates of general intelligence in UK Biobank ↩

-

Deary et al. (2010) The neuroscience of human intelligence differences ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

The Neuroscience of Intelligence by Richard J. Haier ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

Genç et al. (2018) Diffusion markers of dendritic density and arborization in gray matter predict differences in intelligence ↩

-

It’s true that this has something to do with test construction, because IQ test developers tend to want to develop their tests in a way that mitigates bias. Women tend to do better on verbal tests and men on spatial, so you could construct a test that favours one gender or the other in theory. But in general, performance is close enough there’s no particular reason to believe there’s any difference in average IQs ↩

-

Azevedo et al. (2009) Equal numbers of neuronal and nonneuronal cells make the human brain an isometrically scaled-up primate brain ↩

-

Herculano-Houzel (2009) The human brain in numbers: a linearly scaled-up primate brain ↩

-

Olkowicz et al. (2016) Birds have primate-like numbers of neurons in the forebrain ↩ ↩2

-

Herculano-Houzel (2017) Numbers of neurons as biological correlates of cognitive capability ↩

-

Dicke et al. (2016) Neuronal factors determining high intelligence ↩

-

Kaplan et al. (2020) Scaling Laws for Neural Language Models ↩ ↩2

-

Hoffman et al. (2022) Training Compute-Optimal Large Language Models ↩

-

Large Language Models: Scaling Laws and Emergent Properties by Clément Thiriet ↩

-

Schaeffer et al. (2023) Are Emergent Abilities of Large Language Models a Mirage ↩

-

Thermodynamically, systems should be in the phase that minimizes their free energy. Although thermodynamic free energy and Friston’s concept of free energy are not the same, it’s interesting to note the analogy here that phase changes are related to free energy minimization in both senses of the term ↩

-

Foundations of Complex-system Theories: In Economics, Evolutionary Biology, and Statistical Physics by Sunny Auyang ↩

-

Liu (2023) Seeing is Believing: Brain-Inspired Modular Training for Mechanistic Interpretability ↩

-

Power et al. (2022) Grokking: Generalization Beyond Overfitting on Small Algorithmic Datasets ↩

-

I wonder if animals are optimized for quick learning and quick forgetting- there could be some trade-off between learning speed and memory. Do animals with highly variable environments have steeper forgetting curves to help them avoid relying too much on old priors? ↩