Going direct: notes on Eli Lilly at a trillion

A few weeks ago, Eli Lilly CEO Dave Ricks appeared on Stripe’s “Cheeky Pint” podcast. It’s rare1 for pharma executives to make unscripted media appearances (the industry is risk averse by nature), so seeing one sit down with the Collison brothers — on a tech podcast, no less — is notable.

Pharma’s deliberate distance2 has come at a cost: the industry has mostly failed to establish positive relationships with consumers. Tech, by contrast, consistently ranks as one of the most liked industries; pharma is one of the most disliked. Tech CEOs are household names, yet hardly anyone outside the industry can name a pharma CEO.

The hot trend in the tech industry is for founder/CEOs to “go direct” with their communications — this follows the realization that if you don’t tell your story, someone else will (and you might not like what they say). Ricks’ appearance on Cheeky Pint, then, suggests that Lilly’s CEO is starting to act more like a tech founder than a traditional pharma exec.

What makes this interview particularly interesting is that it reveals an ambition to build a new and different kind of machine than the ones being built by Lilly’s competitors. Ricks is adopting the communication style of Silicon Valley because Lilly is starting to adopt its business model.

The episode opens with John Collison asking about Lilly’s recent NVIDIA partnership to build “the industry’s most powerful AI supercomputer”. This isn’t a coincidence; Lilly wants to position itself as a technology company. Stripe as a brand has a great deal of cachet within the start-up, venture capital, and tech community, so it’s a good podcast to go on if you’re a 150-year-old pharma giant that wants to recast itself as part of the tech ‘in-crowd.’

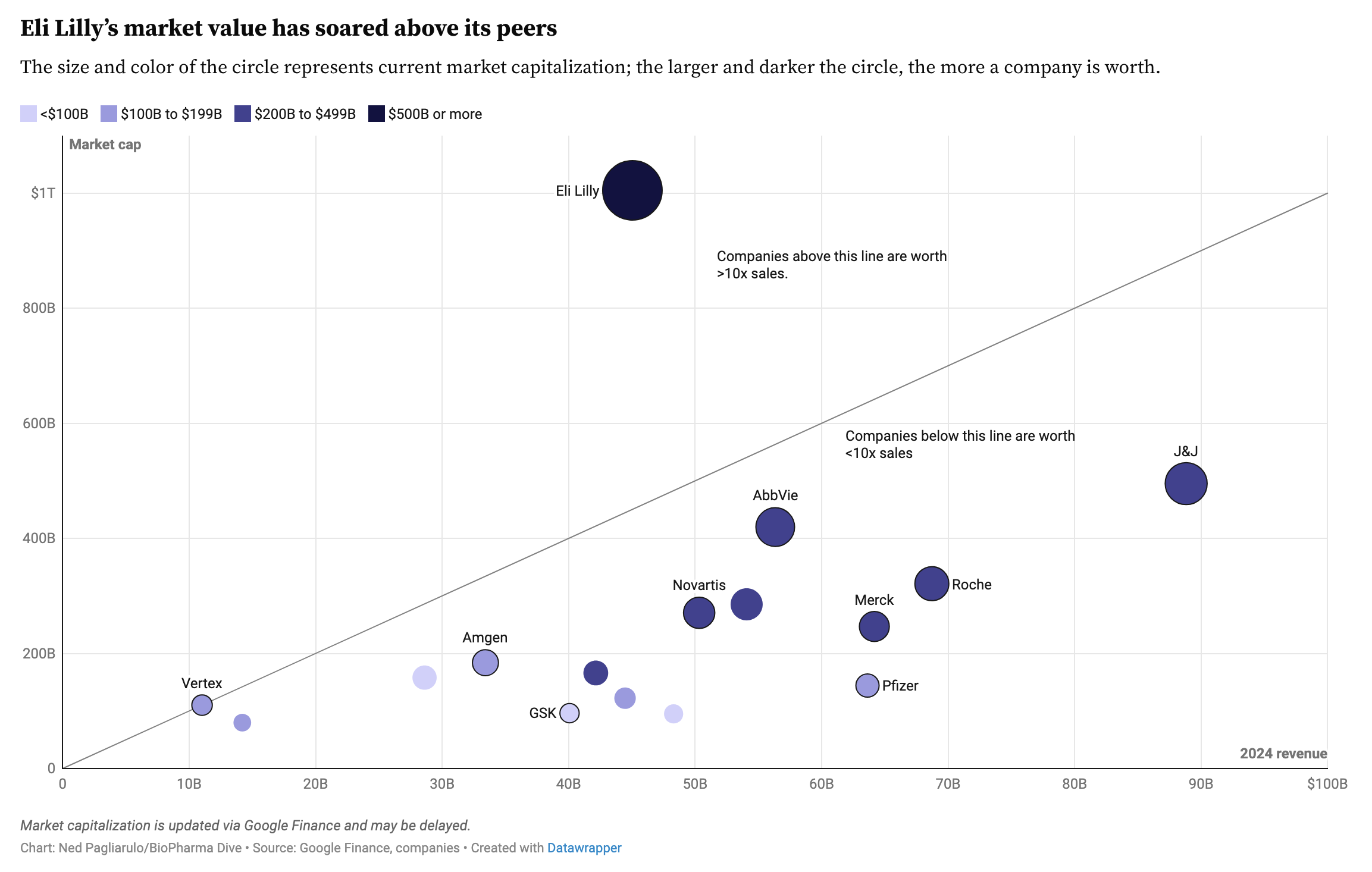

So far, Lilly is doing a good job of achieving tech-like valuations; on November 21st, Lilly became the first pharma company to hit a trillion dollar valuation.

Lilly’s dislocation from its peers is driven partly by massive growth expectations for GLP-1 drugs (with Novo Nordisk, the previous market darling, now presumed beaten). The other factor is a narrative of business model evolution — but we’ll get to that.

Lilly’s revenues are comparable with other pharmaCos, but are growing at a faster rate (~40% year over year, driven by their obesity drug Zepbound). Ricks comments on this:

“…in our sector today, let’s pick a company like Bristol Myers or Pfizer. These are big companies with revenues not so different from ours, and we compete with them in these other spaces. Their market caps have been $200 billion. We’re trading about $800. And that difference is the GLP-1 phenomena.”

So why do GLP-1s make Lilly worth 4-5x more than its peers?

A fundamental constraint of the pharma business model is that discovering drugs doesn’t scale. Each new effort requires solving an idiosyncratic biological and regulatory puzzle with learnings that do not transfer easily to new programs. If you look at drug discovery productivity stats, the evidence best supports some model where companies ‘get lucky’ at a rate that is proportional to R&D expenditures. More dollars and scientists gives you more coin flips, but each flip is still roughly independent.

In a bid to make drug discovery more predictable, the industry shifted in the 2000s towards personalized medicines and ‘programmable’ platforms (CRISPR, mRNA) that target precise genetically defined subpopulations. The hope was that these platforms could be applied across diseases, and yet while many of these genetic medicines do work, the economics often don’t. Because regulation imposes a high fixed cost on development, programs targeting ever smaller slices of the population need to have higher and higher prices to recoup investment (e.g. $2 million gene therapies). I’m still long term optimistic on genetic medicines, but the Zolgensma-era exuberance has mostly died out.

In the interview, Ricks implies that the industry may have gone astray, and actually, going after defined slices of patients with precisely targeted mechanisms has been in some ways the wrong approach for value creation. What you actually want to do is the inverse: go upstream, both in mechanism and earlier in the disease process, and deal with a whole swath of diseases at once.

It’s as if the industry has been digging ever more precisely engineered mineshafts with ever more precision engineered tools to reach smaller and rarer ore deposits, and Lilly rocks up and says: hey, what if we just blow up the whole mountain and collect all the ore at once?

Ricks introduces this thesis by referring to obesity the “master switch” to many diseases. His argument has this structure:

- The default biological set point for caloric intake (“food craving”) is too high

- Because food is abundant in modern life, people tend to overeat

- Excess calories from overeating leads to obesity

- Obesity leads to all manner of problematic pre-disease states: inflammation, cardiovascular comorbidities, and mechanical stress. These eventually develop into full-blown disease

- If people lose weight, they don’t to need consume as much medicine

He introduces this growing scope of GLP-1 applicability as a widening circle:

“So if you think chronic overweight has these untoward effects, our ancestors weren’t chronically overweight, they were chronically starving. So we didn’t worry about this, but now we worry about it, which are type two diabetes, cardiovascular health, atherosclerosis, stroke, MI, peripheral artery disease, kidney and liver diseases, fatty liver diseases, these are all sort of right on that target. Adjacent to that are other conditions we think of as more unrelated, but actually have not a perfect Venn diagram, but close enough. One is sleep apnea. So like 70% of those people with sleep apnea actually have overweight or obesity. Polycystic ovarian disease, as young women get this and they don’t ovulate, they can’t have babies. So that’s a fertility problem. So the circle widens.”

Ricks then broadens the discussion to inflammatory diseases that aren’t commonly thought of as sequelae of obesity. He refers to knee pain as a consequence of mechanical overload and inflammation. Then moves to inflammatory conditions more broadly: psoriasis, Crohn’s, and less familiar diseases:

“…the signature one is a skin disease called hidradenitis suppurativa. A terrible name, but people get basically boils and it’s almost completely correlated with excess body weight. And we have very expensive inflammatory drugs that have fancy targets and are monoclonal antibodies to inject and they cost $4,000 a month, or you can just lose weight.”

Here Ricks is suggesting that caloric intake is perhaps a more fundamental, upstream driver of disease than the pathways hit by modern targeted therapies. It’s implied throughout the episode that GLP-1s (and the adjacent mechanisms like GIP and amylin) will have a scale of impact beyond any other modern medicine (Ricks calls Lilly a GLP-1 company with a “sidecar” of other bets at one point). Like a Google or a Facebook, weight control3 peptides are a scalable consumer product for (almost) anyone:

“Patrick: What fraction of the population, let’s say the population over 35 will be on a GLP-1 in 15 years?

Dave: Well today in the US we probably have 10 million people, maybe 12 if we include the compounded market and non-approved drugs… But it’s really a fraction of the adult population and even if you just take obesity, it should be a hundred million. We have a long, long way to go.”

The thing that distinguishes tech from non-tech companies is that they can serve large markets where scale continually improves margins and, often, also improves the product or entrenches competitive position. Most industries have economies of scale, but they’re clearly bounded — a steel manufacturer spreading fixed costs across more output still faces materials, energy, and labor costs that grow with each ton produced. Tech companies have flywheels that lead to superlinear returns.

Pharma, meanwhile, cannot rest and compound; they need to continually develop, launch, market, and manufacture an ever-growing crop of products just to maintain their position. The core problem is that drugs have a shelf life. Genericization is a gravitational well no company has been able to escape: there is a limited window of exclusivity to recoup your investment before patents expire and generic drugs commoditize your product. This dynamic has historically capped pharma valuations at around $200bn. It also makes these businesses difficult to value because pharma companies are a complex conglomerate of discrete scientific, regulatory, and market risks.

Investors like simple narratives and quantitative relationships they can deploy capital against. Consider AI scaling laws; it is highly “legible to capital” to have a mathematical relationship between capital inputs and value/performance as an output. Lilly has been the beneficiary of exactly this sort of simplifying narrative; you can now model their value creation and capture as a function of total excess caloric intake eliminated:

“John: What would you guess the average caloric consumption per day in America is?

Dave: 3,600 calories.

John: Yeah, isn’t that incredible?

Dave: And here’s an interesting stat: when you’re on our medicine, how many fewer calories do you consume on average?

John: On one of the GLP ones?

Dave: 800 calories a day, it’s 800, which is almost a meal. If you go pull up to In-N-Out Burger—,

John: That’s second breakfast right there.

Dave: Second breakfast, exactly. So that’s why people lose weight so successfully.

Patrick: No wonder all the food companies are so worried.”

So now Lilly’s job actually becomes quite simple: push the GLP-1 distribution lever as much as you can. Here Lilly has found a nice solution: sell directly to patients. This why Lilly set up their own online pharmacy, LillyDirect (which, incidentally, runs on Stripe4). It’s going pretty well:

“$500 a month is a big ask. It’s a car payment, but a fair swath of the US can afford that. **The number one prescribed form of these medications is Zepbound self-buy. We sell more than that than our insured business in new patient starts and more than all of Wegovy.”

But why hasn’t pharma done this before?

Because previously, the economics required intermediaries to bundle the market.

First, pharma needed doctors to bundle demand. Illnesses were specific and hard to identify; the doctor was the necessary aggregator who matched patients to products. Later, as drugs became complex and expensive (specialty oncology, etc.), the system needed to bundle price. Few patients can pay $50,000 per year out of pocket for a drug, so the market relies on insurance pools to spread costs.

The GLP-1 market is the first instance where neither applies. Demand is ubiquitous (doctors aren’t needed to find it), and the price — while high — is within the stretch capability of the middle-class consumer. With high enough volume of demand for a drug, prices can be pushed down, and much of the system becomes redundant. In Ricks’ words:

“I can charge less and get it to more people at scale and I actually don’t really need a healthcare system…You certainly know if you are overweight or obese, you don’t need a doctor to tell you that. And platforms like our direct platform have really taken off because it’s self-paid, but people skip all this other morass and getting a ‘this is not a bill’ piece of paper. They’re just like, ‘Here’s my Visa card number. Yeah, charge me 500 bucks. But my problem’s getting solved.’ I think for prevention, that’s an intriguing future, direct-to-consumer.”

The current healthcare infrastructure has proven to be unwilling to pay for prevention at the scale Ricks envisions. Preventative medicines have historically been difficult to monetize because they don’t fit well into existing care delivery and reimbursement models (which were built for acute interventions).

The business model that Ricks describes is much closer to a consumer subscription model than the established model, and so Wall Street is beginning to value Lilly not as a drug company but as a subscription business with high retention and a massive TAM (one wonders how long until Lilly starts reporting its monthly active users). Ricks explicitly mentions the goal of creating “franchise value” which preserves revenue even when generic competitors arrive:5

“I think Wall Street also believes that our R&D productivity has been higher… And I think the other thing that’s out there is this belief that perhaps… this cycle could be different, this cycle starting with GLP-1s, but that you could create back to the route to market and the consumer much more of a self-pay branded business that has staying power beyond the patent cycle, a franchise value. And I think so far the evidence is pointing that way. Have we fully evolved to a mature version of that? No. Have we created an ecosystem around ourselves like Apple has done? No. Those are all opportunities for us, but you can kind of see them.”

Lilly’s success presents an asymmetrical threat to the rest of the pharma industry. By achieving a tech-like valuation, Lilly lowers its cost of capital significantly which it can weaponize against competition. When the public markets are willing to pay 4x more per dollar of earnings for your stock than your competitors, you have a resource that can be deployed to widen the gap6.

We can state the flywheel strategy as follows:

- Build a large self-pay franchise on the back of GLP-1s (high cash flow)

- Achieve tech-like multiples (low cost of capital)

- Use that revenue stream and cheap capital to take high risk, high reward bets with a focus on high-volume and/or preventative medicines

- Distribute those medicines through the self-pay franchise, and compound franchise value

- Repeat

Ricks describes a ‘rich get richer’ scenario where the success of the current franchise funds bets that are too expensive or risky for peers. One type of bet are “moonshots” (Ricks mentions a potential preventative Alzheimer’s therapy). The other way to leverage their capital advantage is by parallelizing clinical trials — running all necessary studies at once rather than sequentially:

“I think we do three things better than others. One we talked about already, which is cycle time. It’s a basic concept, but if you can make software faster than someone else, you’re going to win. And the same in the drug business…. Often we do serial clinical trials and by the end of the product lifestyle you get the final indication. We’re trying to stack them all into the beginning, so that’s expensive, but we’re in a position to do that. It’s not risky actually.”

Of all the pharma companies, Lilly is the best positioned to find the next business model evolution that allows them to escape competition (for now, at least).

So, why did Ricks go on a tech podcast? Because he’s not running a traditional pharmaceutical company anymore. Or at least, he doesn’t want you to think of it that way.

Thanks to Niko McCarty, Tony Kulesa, and Stephen Malina for giving feedback on an earlier draft of this essay

-

Bourla went on Lex Fridman’s podcast, but I felt that was less successful an appearance (just read some of the YouTube comments) ↩

-

There are good structural reasons for this: the industry sells through middlemen (PBMs, insurers, hospitals, pharmacies) so patients rarely interact with manufacturers directly. Regulatory and legal restrictions on compliant communication make it easier to stay quiet than risk a lawsuit ↩

-

I suspect it won’t be that long before we start talking about GLP-1s et. al. as tools for weight and calorie management, and not strictly as weight loss therapies ↩

-

It’s also interesting to consider what the Collisons are getting out of this. LillyDirect uses Stripe for payments processing, and Stripe’s goal is to move commerce from the physical economy to the internet. ↩

-

Ricks argues that this shift is necessary because the traditional “moat” of intellectual property is eroding. In an age of AI and rapid patent-busting, the chemical matter itself is losing its ability to protect value: “Ricks: what is a patent? It’s a decree to publish your finding to make it a public good, in return for that monopoly. But if the monopoly is debased by 30 Chinese biotechs who feed that patent into a computer, the computer then can imagine chemical structures that have one or two atom differences that don’t fit within the patent and then make that substance, test it, it works just the same. You’ve created basically a shadow generic industry and undermine the patent system itself.” If you can’t protect the molecule, you must protect the channel. ↩

-

This is probably why some companies are so desperate to acquire a GLP-1 ↩