Some questions about biotech that I find interesting

This is a list of biotech-themed questions that I find interesting, inspired by other similar lists. One day, I might turn these into blog posts; if you want to collaborate on a post, chat about anything in this list, or send me relevant readings, please do get it touch!

Table of contents

- What ‘outcomes’ are we getting per dollar of pharmaceutical industry R&D spend?

- Why do large pharmaceutical companies tend to settle around $50 billion in annual revenues?

- Are foundations (or family ownership) the optimal governance structures for large pharmaceutical companies?

- Was externalization good for innovation and the biopharma industry as a whole?

- How much better can we get at pharmaceutical revenue forecasts?

- What does the learning curve for biologics manufacturing look like?

- What proportion of drugs don’t work how we think they work?

- Are we working on the right spatial scales in drug discovery?

- Are historical drug failure rates predictive of future clinical trial failure rates?

- How much of the variance in therapeutic area clinical trial success rates can be attributed to differences in preclinical model quality?

- What is the false negative rate of preclinical testing?

- Where does drug hunting fall on the luck:skill continuum?

- What are examples of drug programs that were ‘smooth sailing’ from start to finish?

- Can a top-down innovation strategy work over the long-term?

- What drugs were developed much later than they could have been?

- What are the ‘approval kinetics’ for new drug modalities?

- What determines the rate at which new transformative drugs are developed?

- Does investment in basic research in a given therapeutic area correlate with therapeutic progress in that area?

- Is the FDA good for industry?

- How is the changing nature of the academic job market impacting biopharma industry innovation?

- Has nature already found most of the useful islands of small molecule structure?

- Are pathogens the reason we age?

- What is cognitive fatigue, and how can it be treated?

- What’s the smallest viable patient population for a new drug?

- What are the biggest ‘stealth’ patient populations?

- What’s the best way to incentivize new models or surrogate endpoints?

- Why didn’t Genentech bring an anti-TNF monoclonal antibody to market?

What ‘outcomes’ are we getting per dollar of pharmaceutical industry R&D spend?

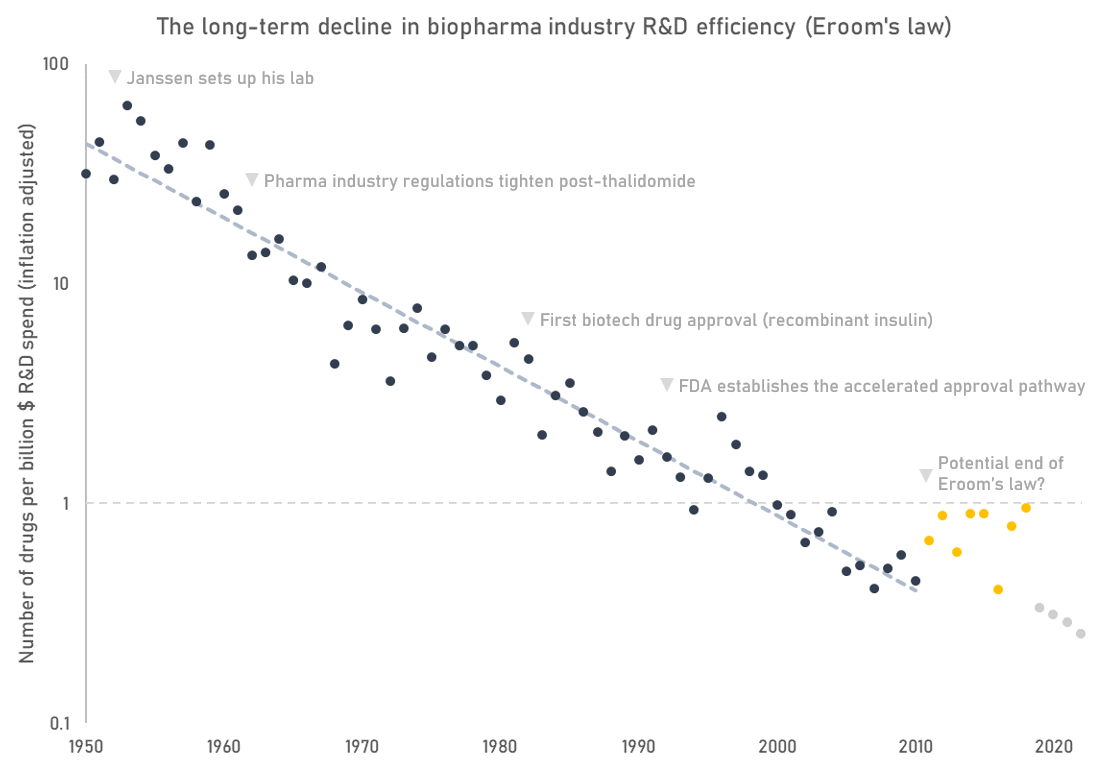

The most commonly used indicator of biopharmaceutical industry R&D efficiency is the number of FDA approved drugs per billion dollars of real R&D spend. On this metric, the trend in industry R&D efficiency looks pretty dismal (see Eroom’s law).

While a useful indicator, Eroom’s law is flawed in some important ways. First, it doesn’t capture an important output of research, which are indication expansions of already approved drugs. Many of today’s leading drugs are approved for multiple indications. For instance, Humira, a top-selling autoimmune disease drug, is FDA approved for 9 separate indications. Second, Eroom’s law mixes the effects of fewer successes with rising costs without giving a clear picture of which factor is driving the trend.

The number of drug approvals is anyway a proxy for the more important question: how much improvement in quality and length of life are we getting for our money? But as far as I know that analysis hasn’t been done. If we plotted R&D spend against some measure of health outcomes instead, would industry productivity look better or worse than it does in the Eroom’s law plot? Is the number of new drug approvals even a good proxy of health outcomes at all?

Why do large pharmaceutical companies tend to settle around $50 billion in annual revenues?

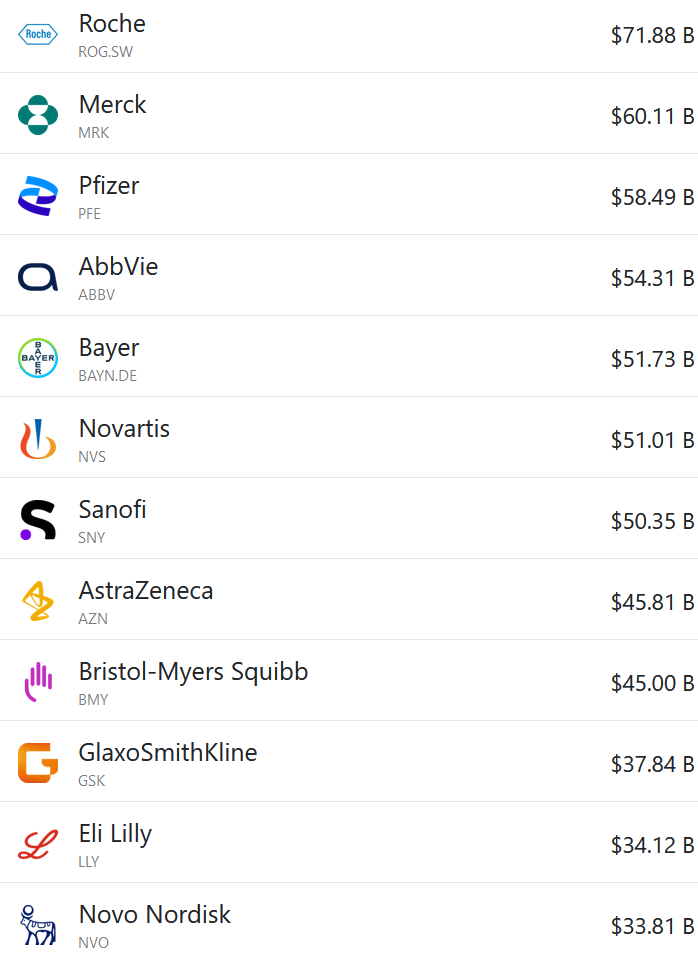

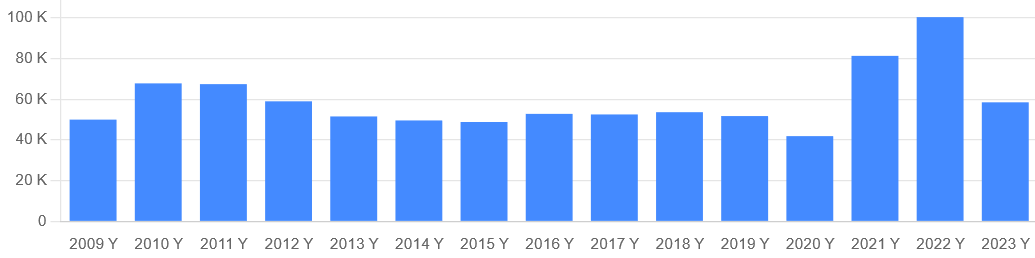

Below are the revenues of some of the world’s largest pharmaceutical companies. The portfolio mix and cultures of these companies are quite different, yet the ‘big pharma’ peer group tends to cluster around $50bn revenue / $200bn market cap.

Individual companies sometimes escape those anchors (e.g. Lilly is now worth about $700bn), but they usually settle back down in line with their peers eventually. Pfizer briefly got to $100bn in annual revenues off their mRNA vaccine and Paxlovid, but they’ve since fallen back down again.

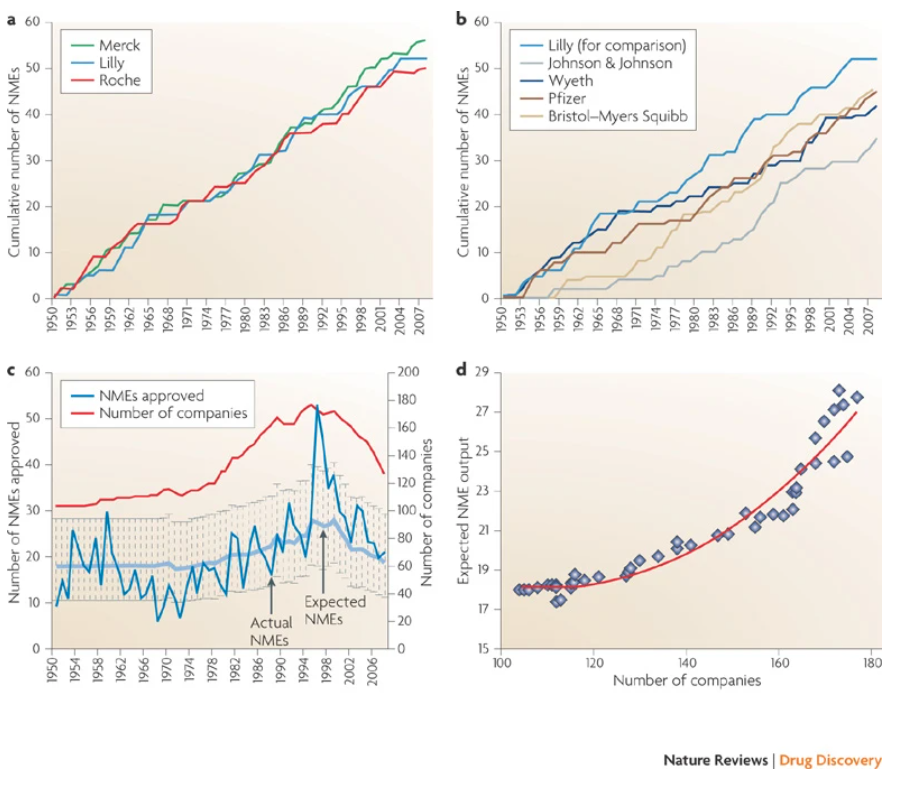

Is this the downstream effect of some sort of iron law of the kinetics of innovation? Different pharmaceutical companies seem to have similar long-run productivity (measured by the cumulative number of new launches, see below). What does this say about the importance of corporate strategy?

Are foundations (or family ownership) the optimal governance structures for large pharmaceutical companies?

Novo Nordisk is owned by a foundation with two objectives:

“To provide a stable basis for the commercial and research activities conducted by the companies within the Novo Group (of which Novo Nordisk is the largest), and to support scientific and humanitarian purposes.”

Novo Nordisk has also been doing well as of late. Is this a coincidence? It’s plausible to me that a foundation is an effective way to prevent companies from succumbing to short-termism, which seems like a useful thing to avoid when drug development programs are measured in decades.

Family ownership (ala Roche) might be another effective mechanism to create this long-term alignment.

Was externalization good for innovation and the biopharma industry as a whole?

It used to be the case that pharmaceutical companies would discover, develop, manufacture, and market their drugs all inhouse. But, increasingly, these functions have been unbundled and taken up by specialist firms. Small biotech companies now originate most new drugs, which large pharmaceutical companies acquire or license from them. Contract research organizations (CRO) do much of the drug discovery work and run clinical trials. Contract development and manufacturing organizations (CDMO) make the drugs. Pharma company employees now spend much of their time managing an army of vendors.

Has this process of unbundling and externalisation helped, harmed, or had no effect on industry efficiency?

The big pharma companies used to have large R&D campuses, many of which are now shut (like Roche’s Nutley site). Did humanity lose out when these sites were closed?

How much better can we get at pharmaceutical revenue forecasts?

Peak revenue forecasts for pharmaceuticals are notoriously inaccurate, whether they are put together by sell-side analysts or by analysts within pharmaceutical companies. According to an analysis in Nature Reviews Drug Discovery, the majority of consensus analyst forecasts are off by more than 40% (see graph). This is important, because most companies use these forecasts to make investment and development decisions.

I’ve personally been involved in creating a bunch of drug revenue forecasts, and it’s true there is often an incentive to inflate estimates (e.g. someone wants a deal done, teams want a bigger budget for their drug program, analysts want to make the companies they cover look good). However, we always made an effort to collect good data and push back on shaky assumptions. Often it’s the known unknowns that lead to inaccuracy. Perhaps there’s scope for Superforecaster-esque techniques to improve outcomes here. Could internal prediction markets be useful too?

Or is accurate pharmaceutical revenue forecasting just intractable?

What does the learning curve for biologics manufacturing look like?

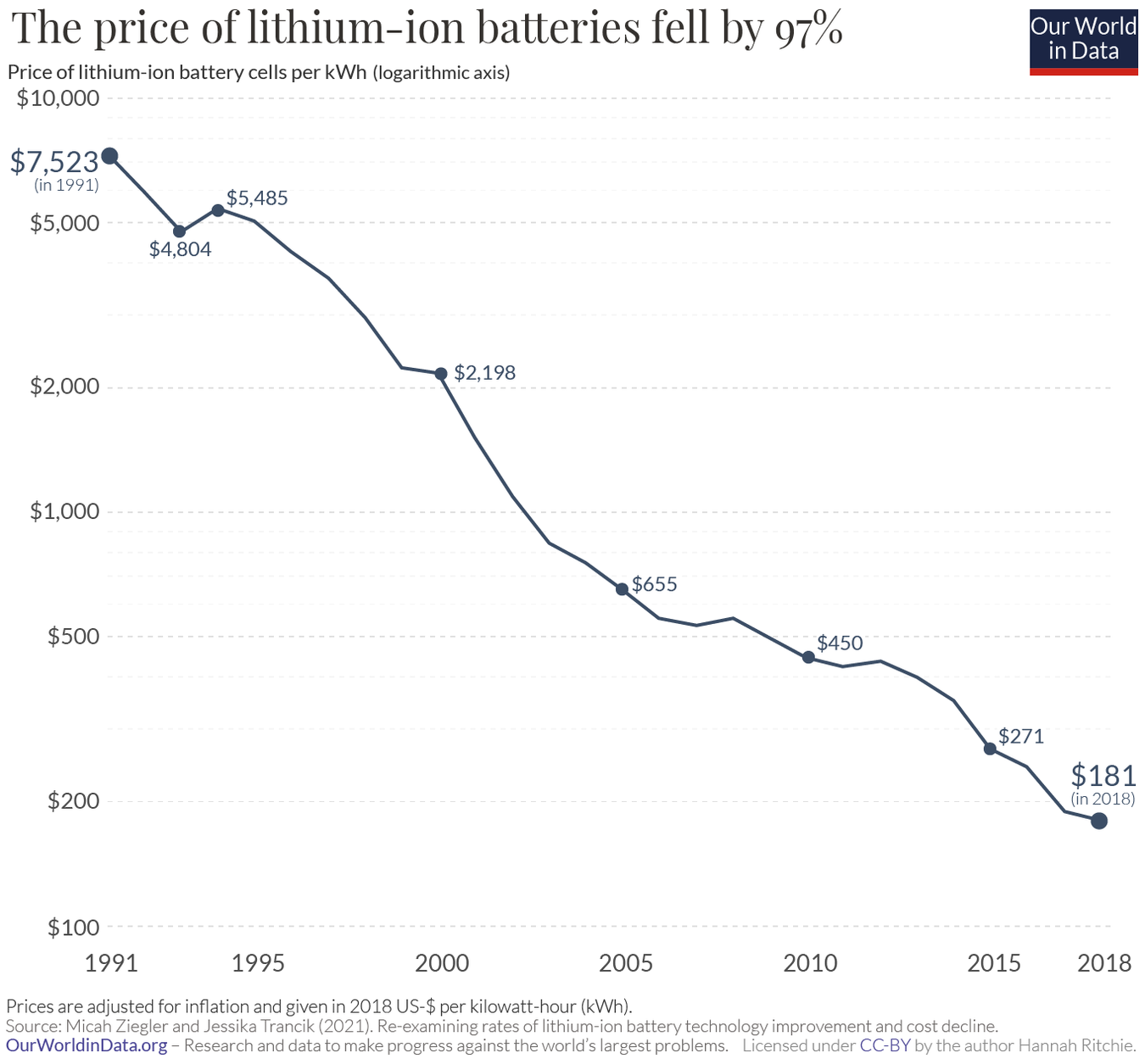

Ourworldindata has some nice graphs on how the costs of various technologies have declined over time (the learning curve). Here’s one for lithium-ion batteries:

Many people are familiar with the graph showing the decrease in the cost of sequencing a human genome over time. But it’s hard to find similar information on drug manufacturing costs. How has the cost to manufacture biologics (monoclonal antibodies, cell and gene therapies, mRNA, peptides, etc.) changed over time?

What proportion of drugs don’t work how we think they work?

In a 2019 study, researchers found multiple examples of cancer drugs used in human clinical trials with wrongly attributed molecular targets. How widespread are these incorrectly attributed mechanisms of action?

In the past, mischaracterised drugs have chilled interest in further development of follow-on compounds against an otherwise promising target (e.g. inaparib, the ‘pseudo’ PARP inhibitor)

This type of mischaracterization also contributes to a ‘noisy’ scientific literature, which complicates the lofty ambition of ‘training AI on all of the literature and having it solve science.’ For example, dapansutrile is widely claimed to be an NLRP3 inhibitor in the scientific literature, but it’s probably not.

Are we working on the right spatial scales in drug discovery?

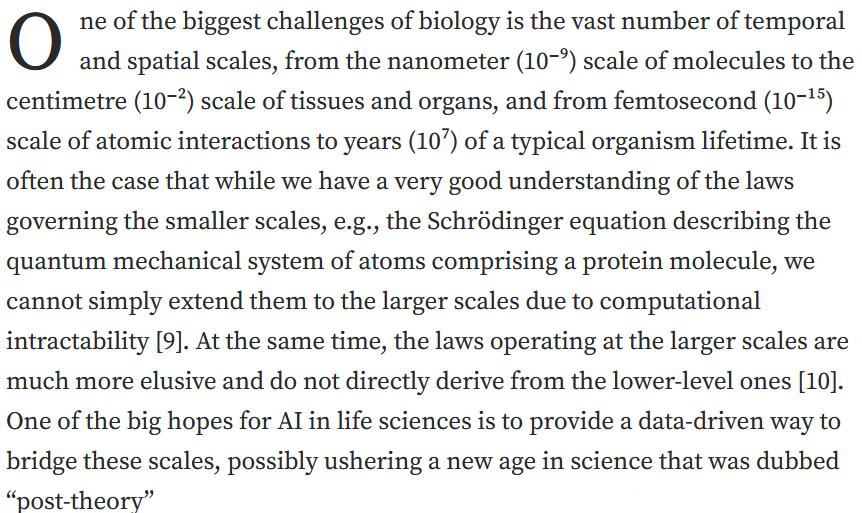

Biological systems operate over huge scales of time and space. I like how Luca Naef and Michael Bronstein state this problem in their post on AI in drug discovery:

Most drug discovery work focuses on the smaller end of this scale: drug targets are most often proteins. But lots of interesting biology happens at the level of networks, tissues, and whole organisms.

Have we spent too much time looking at the smallest scales? Is target-based discovery a waste of time?

What should we make of relatively large-scale effects that seem to have some function e.g. ephaptic coupling? Are they druggable? Should we be paying more attention to effects at hierarchies above the level of the target or cell?

Are historical drug failure rates predictive of future clinical trial failure rates?

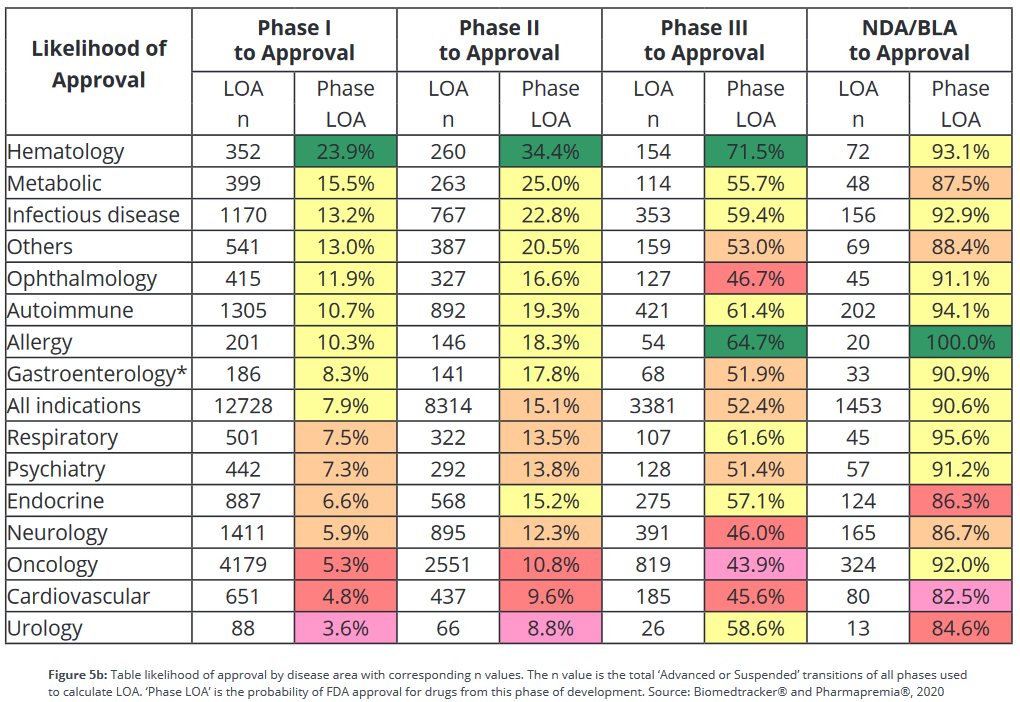

Based on historical data, the overall probability of a drug making it from phase 1 to approval is about 10%. However, these success rates differ greatly between therapeutic areas. According to BIO’s data in the table below), a hematology drug is almost 7 times more likely to make it from phase 1 to approval than a drug for a urological condition.

The industry uses this sort of success rate data to help pick projects to invest in, but since success rates are backwards looking, is this a good idea? What’s the correlation of historical success rates with future ones?

How much of the variance in therapeutic area clinical trial success rates can be attributed to differences in preclinical model quality?

The quality of preclinical models can have a large effect on our ability to surface good new drugs. For example, new models of hepatitis C viral replication spurred the discovery of curative treatments like Sovaldi.

As noted above, clinical development success rates differ substantially between therapeutic areas. How much of this difference is down to differences in the quality of preclinical models? How much is down to other factors?

How strong is the causal relationship by which better models lead to better drugs? If it’s very high, then we should be investing much more in better preclinical models than we are today.

What is the false negative rate of preclinical testing?

Almost all investigational drugs go through some form of animal testing before they’re tested in humans. Yet, 90% of drugs fail in clinical trials anyway. This false positive problem is well-recognized and highly visible; there are many examples of drugs that cured mouse models but failed to work or were toxic in humans.

It stands to reason that the inverse is also true: there exist drugs that would have been effective treatments for humans, but since they didn’t work in mice (or some other animal model) they never made it into clinical development. But how many good drugs are in this invisible graveyard?

What’s the best drug that never got developed?

Where does drug hunting fall on the luck:skill continuum?

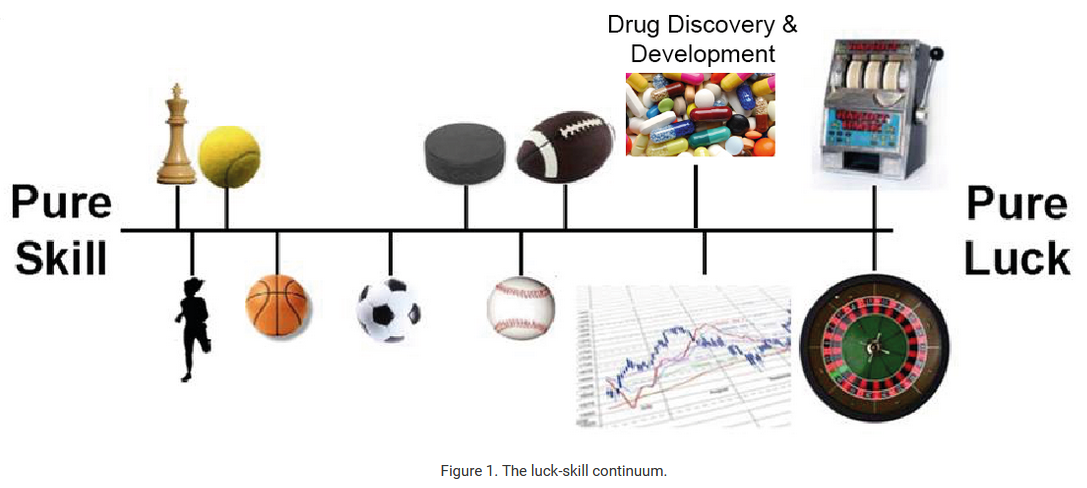

In his book “The Success Equation”, Michael Mauboussin introduces the luck:skill continuum: the tendency for activities to fall on a spectrum from pure skill to pure luck. Something like chess is pure skill, and slot machines are pure luck. Football or baseball are somewhere in the middle.

The performance of some drug hunters, like Paul Janssen, is too good to be explained by luck. But most of the examples of highly prolific drug hunters are from the mid 20th century, so it seems probable that the benefit of skill has been arbitraged out over time. This can likely be attributed to something Mauboussin calls the paradox of skill: as the level of skill increases and gets more consistent in any competitive pursuit, luck becomes more important and has a greater role in influencing outcomes than in an environment with high skill variance.

Yet some companies do seem to be consistently successful: Vertex, Regeneron, Lilly. What do these top teams have in common? Are those commonalities even predictive of anything?

So how much does skill matter now?

As a corollary to the above: where does biopharma business development (BD) fall on the luck:skill continuum? Who are the best BD teams, and what can other companies learn from them (if anything1)?

What are examples of drug programs that were ‘smooth sailing’ from start to finish?

I’ve previously collected examples of how the fates of even the most successful drugs were swayed by chance events, and how often the programs that went on to define a company were underappreciated for long periods of time. Similarly, many ultimately successful biotechs needed to pivot along the way.

Are there examples of drug development programs that we got right from the start, with everything proceeding as planned from start to finish? That both scientists and management agreed would be a good idea?

Where are the triumphs of rational planning?

Can a top-down innovation strategy work over the long-term?

By top-down innovation I mean the process of choosing markets or unmet needs, then developing drugs against those positions. By bottom-up I mean doing basic fundamental research and following the science where it leads.

A top-down innovation strategy is typically associated with the professional managerial class, or MBAs. A bottom-up innovation strategy is typically associated with scientists.

Many of the most impactful drug were discovered bottom-up. Top-down planning has some successes too, but can you rely on it?

What drugs were developed much later than they could have been?

In his post “Why did we wait so long for the bicycle?”, Jason Crawford says:

“The bicycle, as we know it today, was not invented until the late 1800s. Yet it was a simple mechanical invention. It would seem to require no brilliant inventive insight, and certainly no scientific background.

Why, then, wasn’t it invented much earlier?”

Are there analogous examples in drug development? What drugs seem like they should have been developed earlier than they were?

Historically, it takes upwards of 20 years for new drug target discoveries to lead to new medicines. Is that about as fast as we could do it?

What are the approval kinetics for new drug modalities?

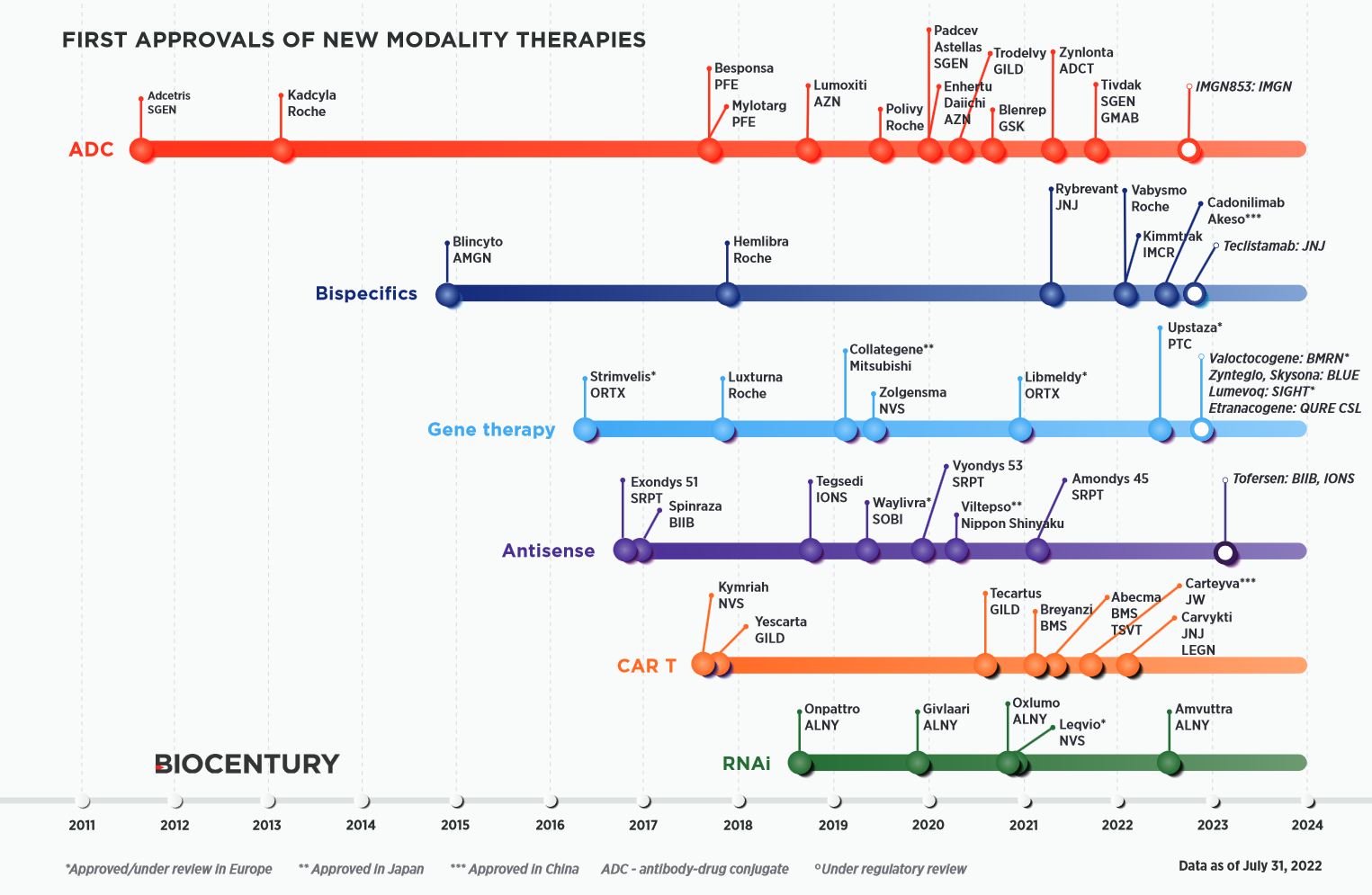

BioCentury has a neat chart of how various types of new drugs have accrued FDA approvals over time.

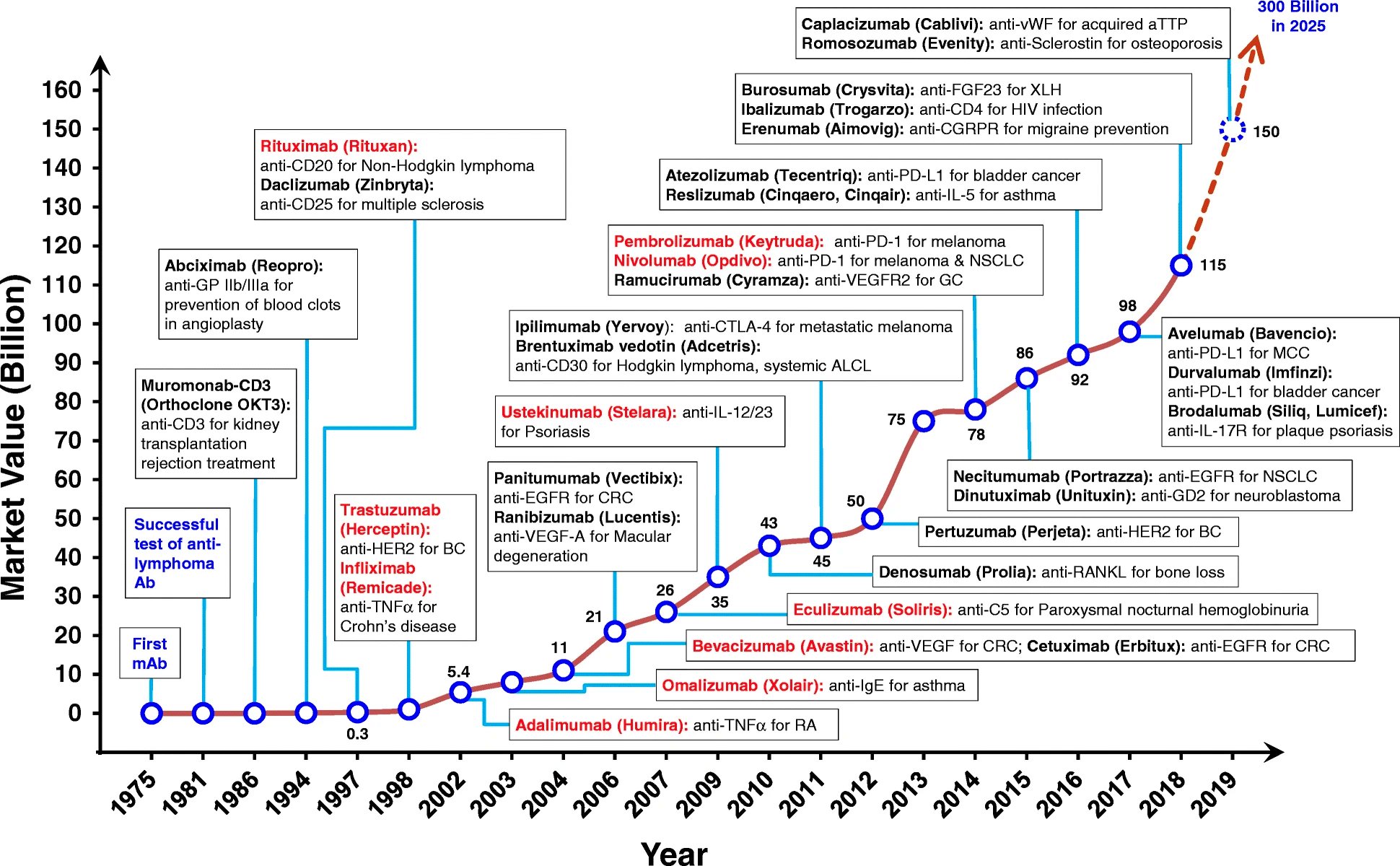

There’s usually one or two approvals early on, followed by a gap, then a later wave of approvals. This trend is more pronounced in the history of monoclonal antibodies (mAbs), shown in the chart below. The first FDA-approved mAb came in 1986, but it took another decade for approvals to begin to accrue with some pace.

Do approvals of new modalities follow a predictable pattern? What are the determinants of these approval kinetics?

What determines the rate at which new transformative drugs are developed?

Most treatments are incremental, a few are “transformative” — far better than anything else available for the condition they treat.

Some examples of transformative treatments include:

- Gleevec

- Sovaldi / Harvoni

- Vertex’s cystic fibrosis drugs (Trikafta, Kalydeco)

- Spinraza

- Keytruda / Opdivo

- ribociclib

- CAR-T therapies

- Opioid painkillers

- Penicillin

- Surgical anesthesia

How often do transformative treatments come around? And how? Is it just luck, or are there ways we could produce them more reliably?

Does investment in basic research in a given therapeutic area correlate with therapeutic progress in that area?

We spend a great deal of money on research into diseases like Alzheimer’s, but we have few good treatments. Similarly, the “War on Cancer” didn’t live up to its ambitions (although we’ve made a lot of progress). In general, how reliable is spending a lot of money as a means to generate new, effective, drugs?

Matt Clancy responded to this question: “I know of two papers that have looked at this question. The earlier one, Toole (2012) is basically a correlation study but it shows that therapeutic areas that receive more NIH research funding do tend to see more drug applications later. The second, Azoulay et al. (2019) makes some progress towards causal identification. It exploits NIH funding rules to argue that in each year, some diseases get research funding based on certain fields of science for basically random reasons. They then look at how many biomedical patents we end up getting that cite (or are related) to research funded by this “windfall” funding. They find a pretty strong relationship - more funding for a disease-science area, more patents.”

Is the FDA good for industry?

There’s lots of handwringing about how the FDA is holding back progress, but is it plausible that the presence of a regulator spurs progress?2 How would we know?

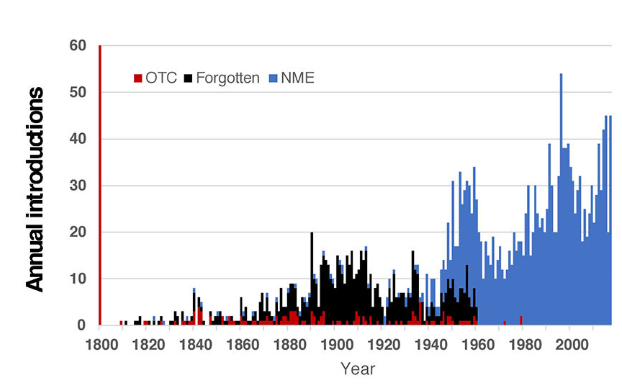

Post the 1962 FDA amendments, many drugs were taken off the market, but the rate of annual new drug introductions increased after the amendments. Would this have happened anyway?

Why are drugs the only biotechnology / synthetic biology product that seem to have long-term sustainable business models associated with them? Does it have anything to do with the regulatory pathway? Did it force maturation?

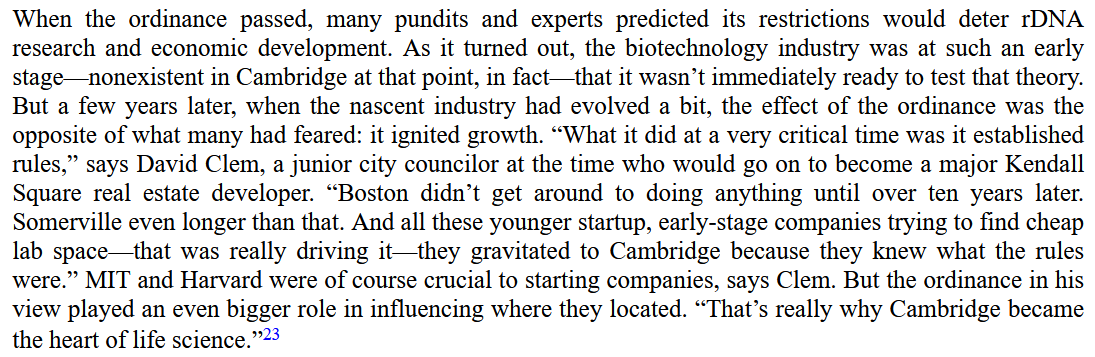

The book “Where Futures Converge” claims that the early adoption of regulations (“the ordinance”) governing the use of recombinant DNA in Cambridge helped establish Kendall Square as a centre of biotech innovation:

Patents are also well-established to be pro-innovation in the biopharma industry. Could this also be true of the drug regulators?

As a corollary to the above: How different would the biopharma industry be today if the FDA was more consistent across departments? For example, the cardiorenal division is generally perceived to be harsher than the oncology division. The industry today spends much more on cancer drug development than heart or kidney disease treatments.

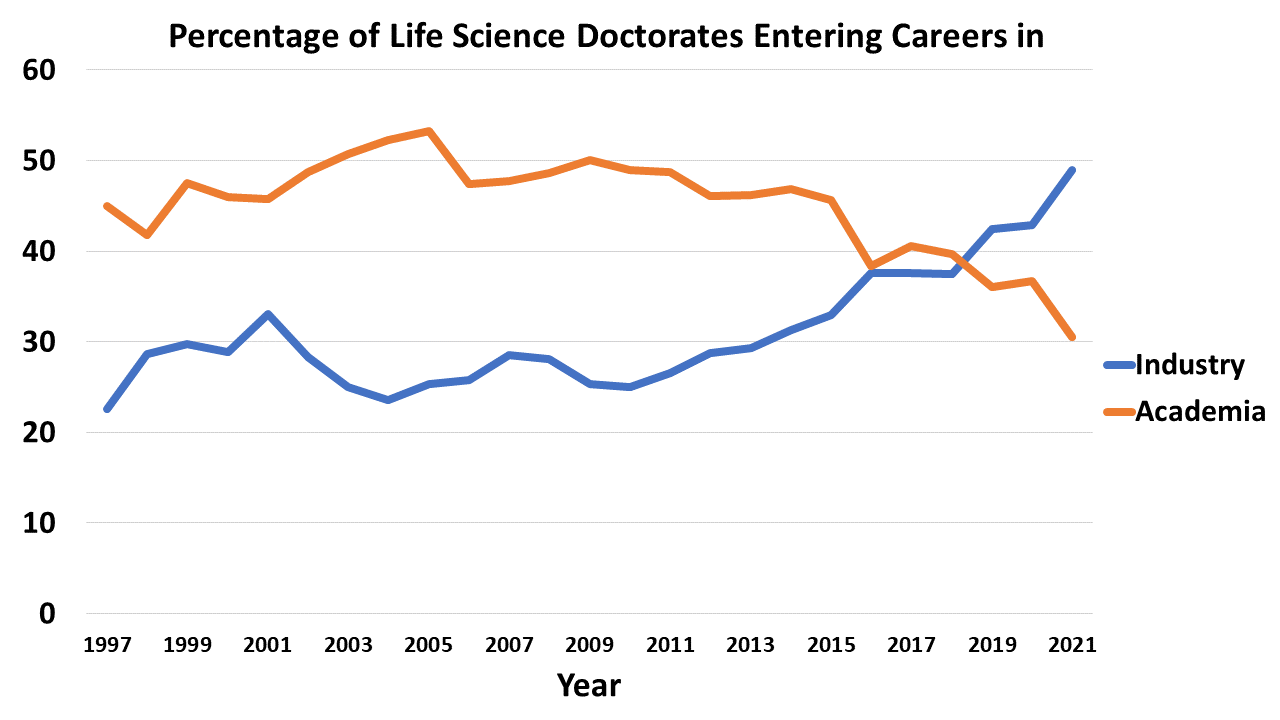

How is the changing nature of the academic job market impacting biopharma industry innovation?

Academia has long been an important feeder into the life sciences industry of both talent and ideas. But, there’s an ongoing exodus of talent from academia and into industry. Postdoc positions, once competitive, are going unfilled.

What does this mean for the biotech industry? Will we have a dearth of new good ideas for drugs in a few years? Will industry take on a greater share of basic research?

Has nature already found most of the useful islands of small molecule structure?

It’s reasonable to ask how it’s even possible to find useful drug molecules at all given the vastness of chemical space (over 10^60 possible drug molecules). One possible answer is that nature, through evolution, has chanced upon many bioactive molecules, and we are mostly building off that inheritance. In support of this are data showing that the screening libraries that we use as the starting point for new drugs are biassed towards drug molecules with natural origins.

But how much of these useful molecules has nature already found? Think of the structure-function space as a landscape with peaks of useful functional structures scattered around in an otherwise flat landscape: how many of these peaks has nature already found, and how many are left to be discovered? Our strategy to explore this structure-function space (e.g. using AI) seems like it should depend a lot on our assumptions about how good nature is at sampling the landscape.

As a corollary to the above: What’s the expected productivity of new natural product screening programs? What’s the likelihood there are undiscovered wonder drugs somewhere deep in the Amazon rainforest?

Are pathogens the reason we age?

Our genomes are polluted with the fragments of ancient viruses (e.g. transposons like LINE-1). We seem to keep discovering new causal links between viral infections and diseases, like EBV and multiple sclerosis. Endemic pathogens like Toxoplasma affect our psyche.

The immune system is meant to protect us from these threats, but it also goes wrong with some regularity and is associated with all manner of disease processes from atherosclerosis to Alzheimer’s.

It seems plausible that our bodies accumulate so much damage from infectious agents over time that it’s easier to start fresh than clear it all away. Is damage accumulation and aging the consequence of multi-billion year arms race between pathogens and immune systems?

What is cognitive fatigue, and how can it be treated?

Cognitive fatigue is one of the most pernicious symptoms of multiple sclerosis (and other diseases), but what is it? Why do patients experience fatigue the way they do? Can we link brain states to the conscious perception of fatigue?

Most disease modifying treatment for MS don’t have much effect on fatigue. Why is this? What would it take to treat fatigue effectively?

What’s the smallest viable patient population for a new drug?

Lenmeldy was recently approved by the FDA for metachromatic leukodystrophy (MLD) with a list price of $4.25 million, the highest list price yet for a drug. However, MLD is ultra-rare, with a prevalence of something like 1 in 75,000 births (this corresponds to ~50 patients per year in the us). Lenmeldy might make a couple hundred million in annual revenue, considered a relatively small sum in the pharmaceutical industry.

MLD is ultra-rare, but there are many conditions that are rarer. Some affect as few as 1 or 2 births a year in the US. Will it ever be viable to develop drugs for these patients considering the huge costs of drug development? What’s the ceiling on the price of curative therapies go? Will we have a $10 million dollar gene therapy soon? $50 million?

What are the biggest ‘stealth’ patient populations?

New drug launches can increase the prevalence of a condition in two main ways:

- By increasing disease recognition, and incentivising diagnosis and treatment-seeking (e.g. Soliris in paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria, Vyndaqel in amyloidosis)

- By helping patients live longer (e.g. Trikafta in cystic fibrosis, Spinraza in spinal muscular atrophy)

It’s not uncommon for the prevalence of a condition to be underestimated when there’s no effective treatment for that condition. Because these markets seem small initially, companies are often reluctant to invest — only to lose out when someone else is bold enough to make a bet.

What other conditions aren’t getting the attention they should be getting because people (wrongly) think the prevalence is too small for profitable development?

What’s the best way to incentivize new models or surrogate endpoints?

New disease models and surrogate endpoints help us discover better drugs and develop them faster, but individual companies aren’t necessarily strongly incentivised to invest in this kind of R&D when they could instead invest in a drug program. However, government funders like the NIH are also likely to see this type of work as being too applied for their tastes.

Who should take the reigns here? Focused research organisations (FROs) seem like a promising class of torchbearer.

Why didn’t Genentech bring an anti-TNF monoclonal antibody to market?

Anti-TNF monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) are one of the biggest drug classes ever by revenue. Humira alone did about $20 billion in annual revenue at its peak. It seems like every big pharmaceutical company except for Roche/Genentech had an anti-TNF mAb on the market at one point.

Genentech were the pioneers of therapeutic mAbs, so it seems strange that they missed out. Genentech had an anti-TNF mAb in house early on, but it seems as though it wasn’t developed for autoimmune conditions. They did test an anti-TNF mAb in cancer, but it failed. Perhaps that dissuaded them from further development against the target.

-

I once asked a BD client of mine what he thought differentiated BD teams who consistently make good deals from those who consistently make bad ones. He said BD activity was mostly downstream of corporate strategy, so the C-suite is to blame for poor BD performance. In his view, bad deals often get forced through by senior management who are under pressure from investors to make something happen. ↩

-

I offered some speculative reasons for how the FDA might spur progress in this post ↩