Will all our drugs come from China?

I’m no car expert (I don’t even drive), but my cofounders used to work at a company called Applied Intuition that develops self-driving software for automakers. Over lunch we often talk about the similarities and differences between the pharma and auto industries, and one of the themes we keep returning to is the impact that innovation from China is having on established Western firms.

The big Western original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) — Volkswagen, Ford, BMW, GM, etc. — are facing an existential threat from Chinese OEMs that relatively recently began to push the bounds of performance, cost-efficiency, driver experience, and autonomy1. For too long the Western carmakers have been content to innovate in a gradual way; a bit more engine performance here, some new trims there — a few software integrations even (CarPlay!). Meanwhile, the ongoing technology transition from combustion engines to electric vehicles (EVs) gave Chinese manufacturers an opening to move from parts suppliers to car manufacturers in their own right.

A defining characteristic of the new wave of Chinese EVs is how they vertically integrate software and hardware in a way that’s hard for the stuck-in-their-ways Western companies to replicate; the pressure to respond to this has been a big driver of Applied Intuition’s partnerships with Western OEMs e.g. with Porsche. If you want to get a sense of how far ahead some of the high-end Chinese cars are check out this review of a futuristic Yangwang SUV.

So the big question in the auto industry right now is whether the West will cease to be competitive. In biotech, too, some are beginning to ask that question.

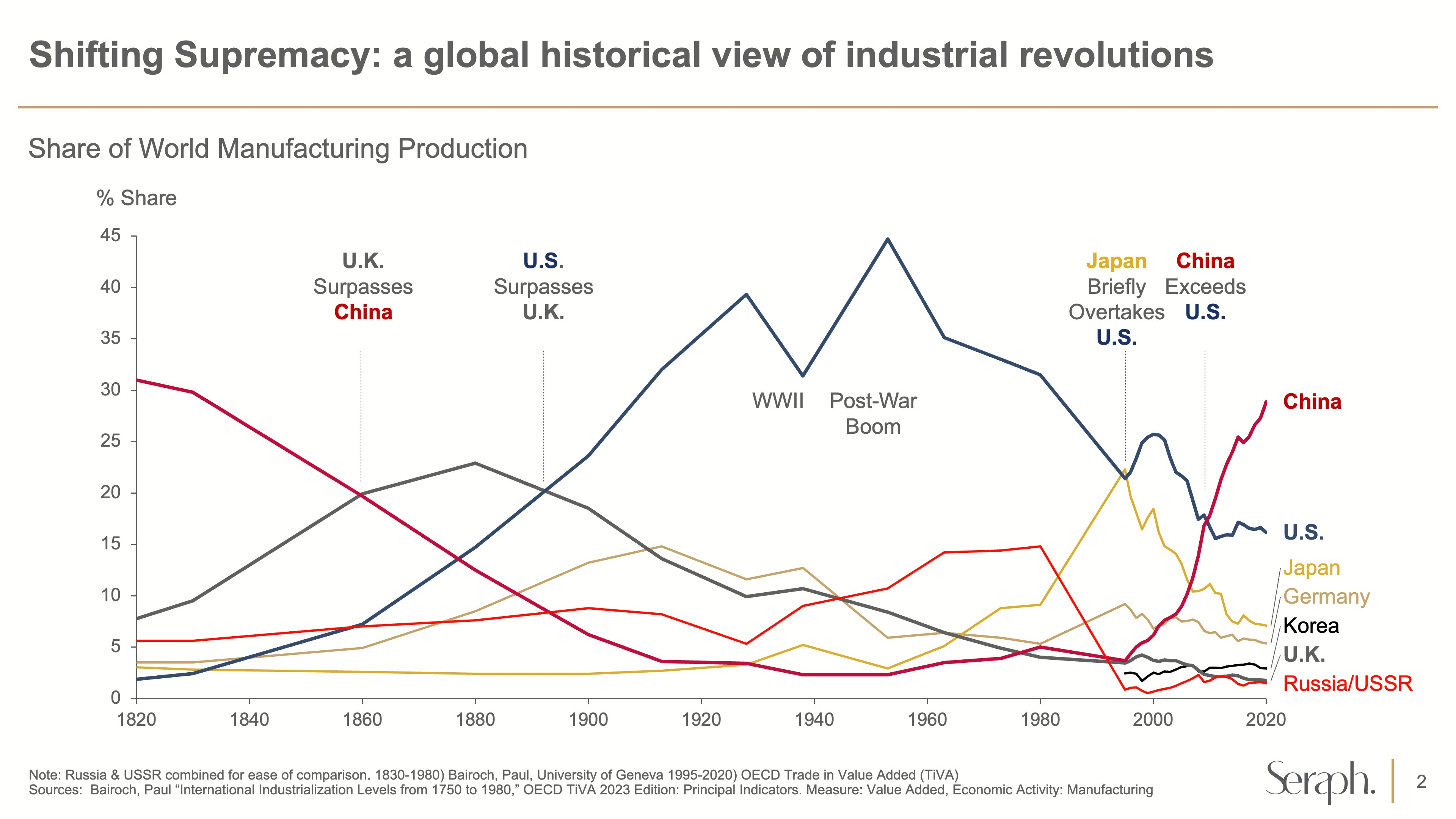

Westerners are used to thinking of China as as a manufacturing powerhouse, a country that makes the parts for cars and iPhones and the latest viral children’s toy. We’re also used to thinking of China as a place that can copy well; good at making generic drugs and cheap knock-offs of fad kitchen gadgets. I don’t think many in the West have yet fully internalized a mental model of China as a source of genuine innovation.

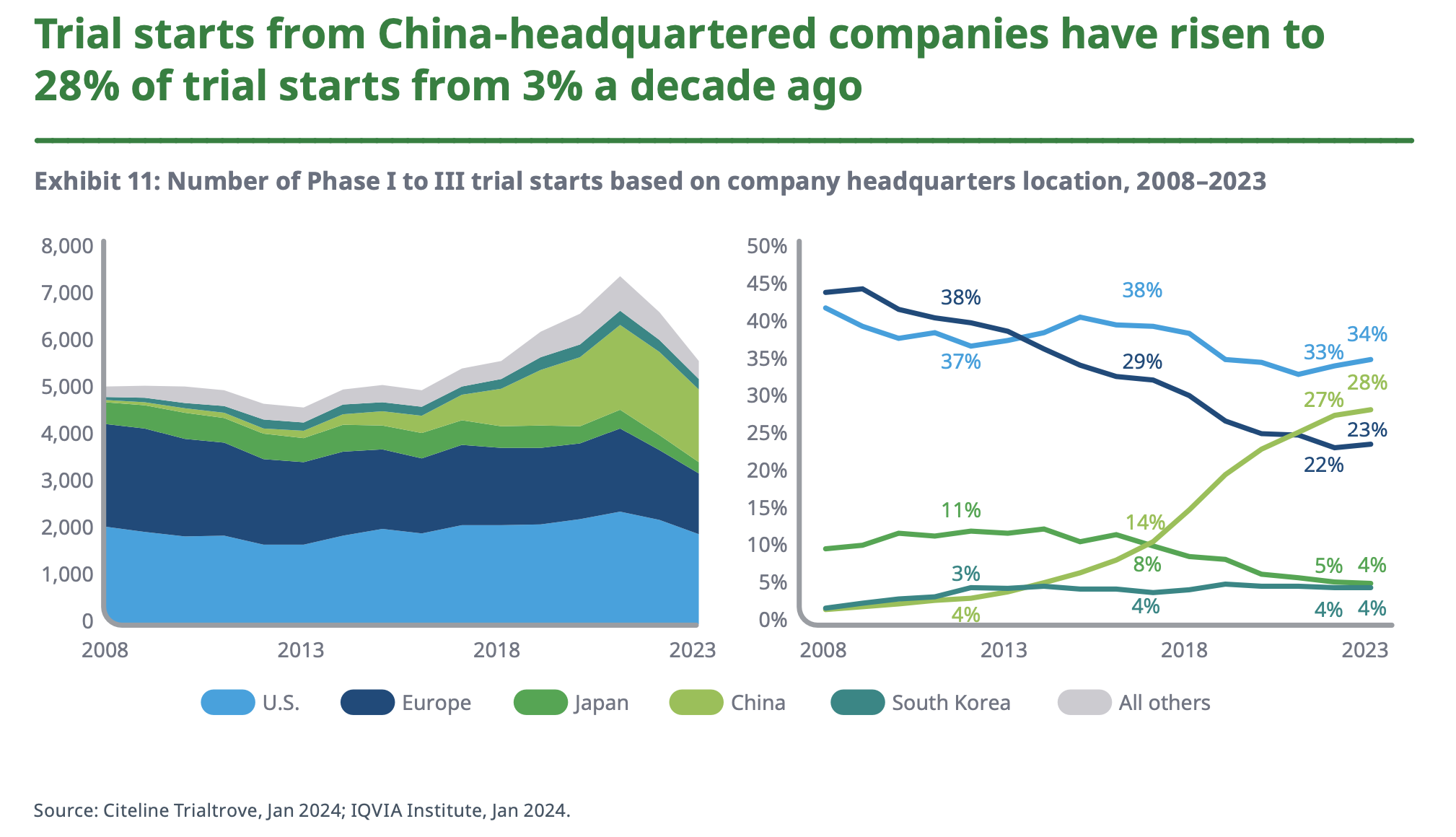

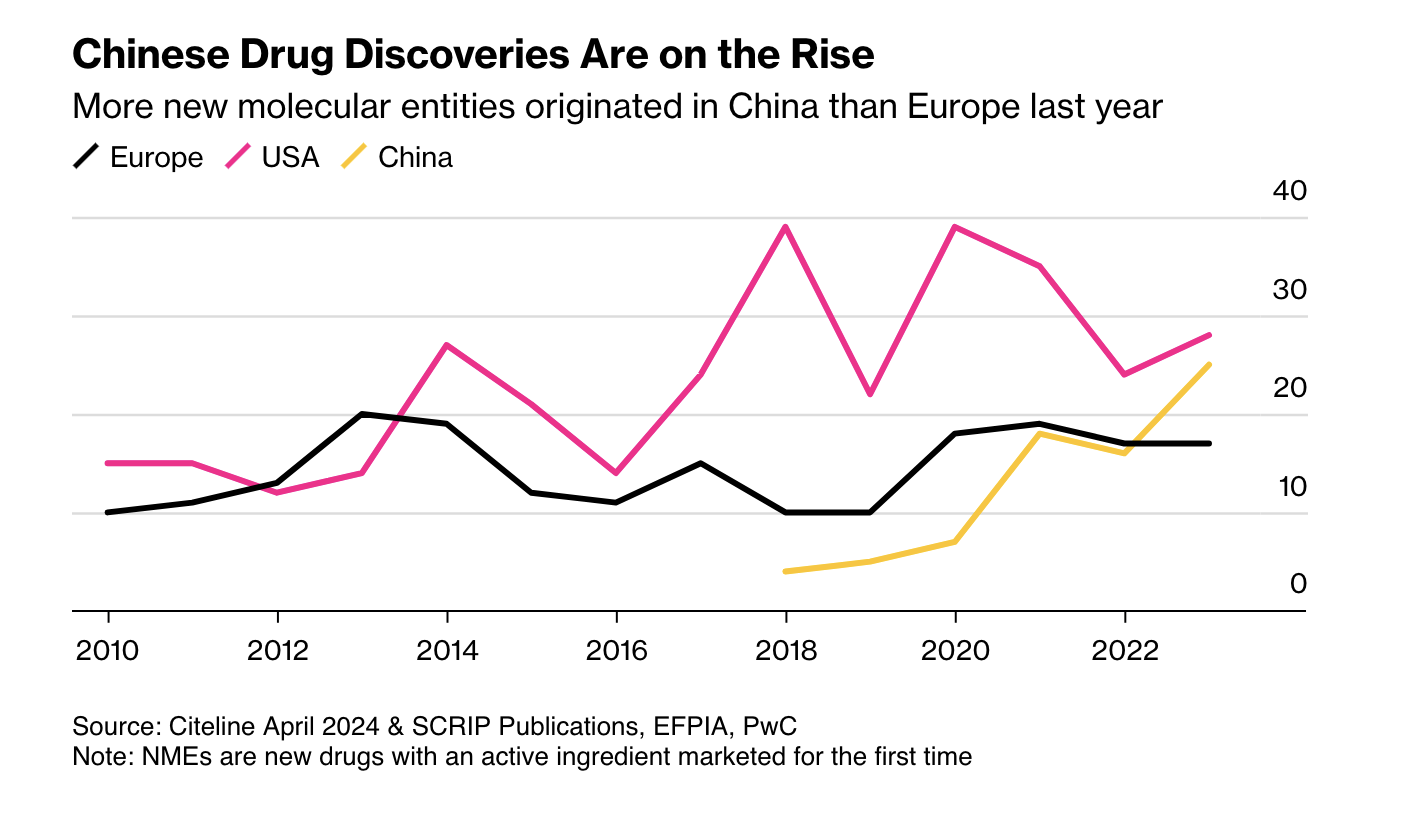

It was not too long ago that China’s main contribution to the pharma industry was the raw chemical material, the active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs), that went into finished drug products discovered, designed, and developed by Western (and Japanese) innovators. However, if you’ve been paying attention, you’ll have noticed the steady rise in Chinese companies as a source of genuinely new drugs (i.e. drug discovery). Chinese companies are now responsible for about a quarter of new trial starts — more than Europe. It is in early-stage (phase I), oncology, and cell and gene therapy where Chinese companies are particularly active.

These trends are covered in a recent (highly recommended) article in Bloomberg on the rise of Chinese biopharma. The growth continues at a rapid clip, the Chinese investigational drug pipeline has doubled in size over the past three years (according to an analysis in Nature, the number of original Chinese drugs in development grew from 2,251 on July 2021 to 4,391 on January 2024). Again, Europe is the loser here; more novel drugs (new molecular entities) are originated in China now than in Europe.

This bounty of novel drug matter is attracting Western pharma companies, who are increasingly looking to China to fill their drug development pipelines. Major Western pharma companies like Lilly, AstraZeneca, and GSK have established significant business development presences in China, often in Shanghai’s Zhangjiang Hi-Tech Park. Per Bloomberg:

“Every major drugmaker’s head of R&D has been to China at least once in the last year… AbbVie Inc. and Bristol-Myers Squibb Co. have hosted dedicated partnering days in Shanghai to meet with local companies, while companies like Roche Holding AG, Bayer AG and Eli Lilly & Co. have opened or will open incubators to build relationships with early-stage startups. At a recent, widely watched trade expo, Pfizer Inc. announced it will invest $1 billion in China over the next five years, in part to work with local companies.”

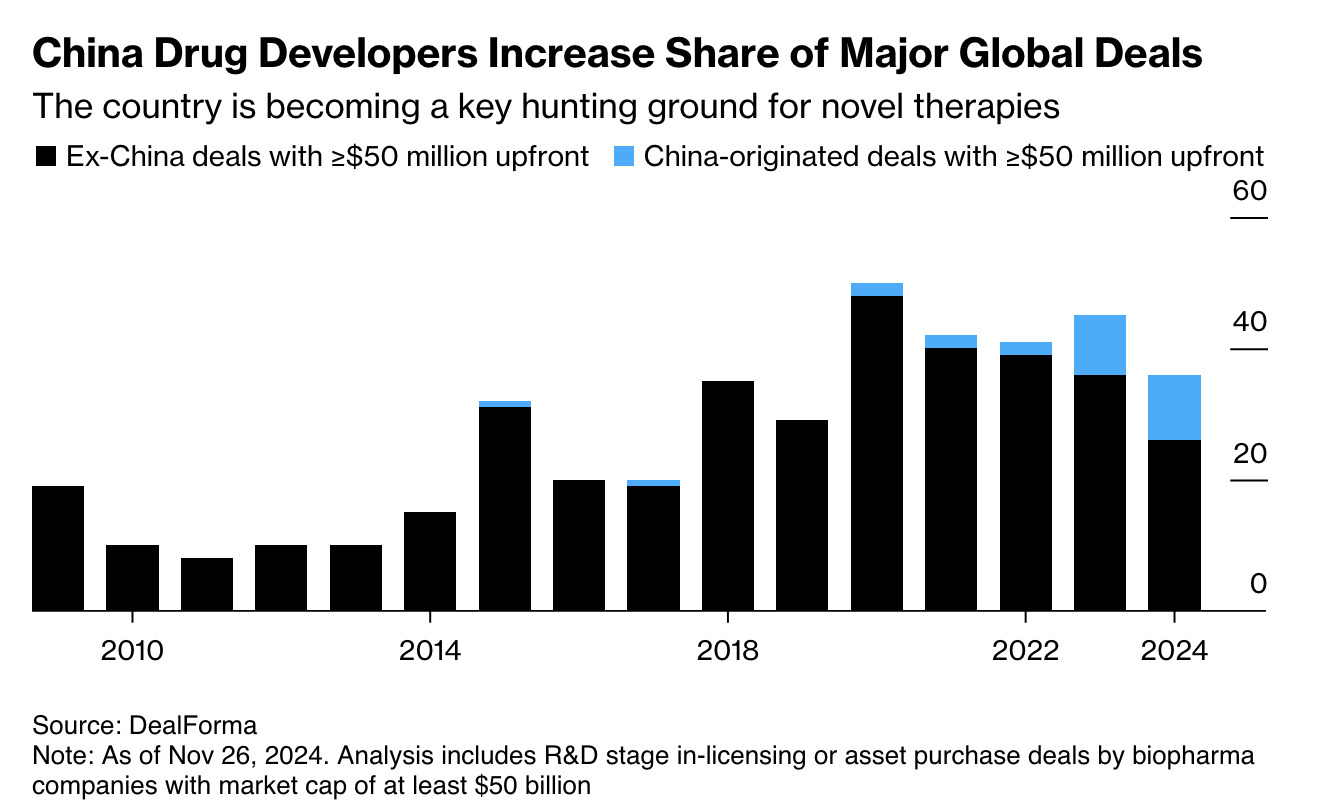

Ten years ago, a major pharmaCo seeking their next breakthrough molecule would have turned to an American or European biotech. Today, they’re just as likely to license a molecule from a Chinese company. Chinese companies will often run the phase I trial in China for cheap, then flip it to a Western pharmaCo to run the expensive US trials and bring the drug to market. This arrangement is favorable to both parties, and Bloomberg’s analysis shows Chinese assets now represent a substantial fraction of major global licensing deals.

At this point there have been dozens of notable Chinese-Western drug licensing deals, but one that stands out in my memory is J&J’s licensing of Carvykti from China’s Legend biotech back during the cell therapy craze of 2017. Carvykti is now FDA-approved for the treatment of multiple myeloma.

The Carvykti deal is particularly interesting for a few reasons:

- It was early (in 2017), before most in the industry were taking Chinese innovation seriously

- Carvykti is a CAR-T cell therapy, a class of drug that reengineers human immune cells to attack tumors. This is a new and complex class of drug, a long way from simple molecules like aspirin or penicillin. The first CAR-T therapy was approved by the FDA in 2017, so this deal showed that China was capable of quickly catching up to the innovation frontier

- Carvykti is extremely effective, 98% of patients with tough to treat (relapsed or refractory) myeloma respond to treatment, and these responses are durable. The early data was so good that many commentators at the time were skeptical that it was real, and suspected that J&J wouldn’t be able to replicate it in the US follow-up trials necessary to secure FDA approval (spoiler: it replicated)

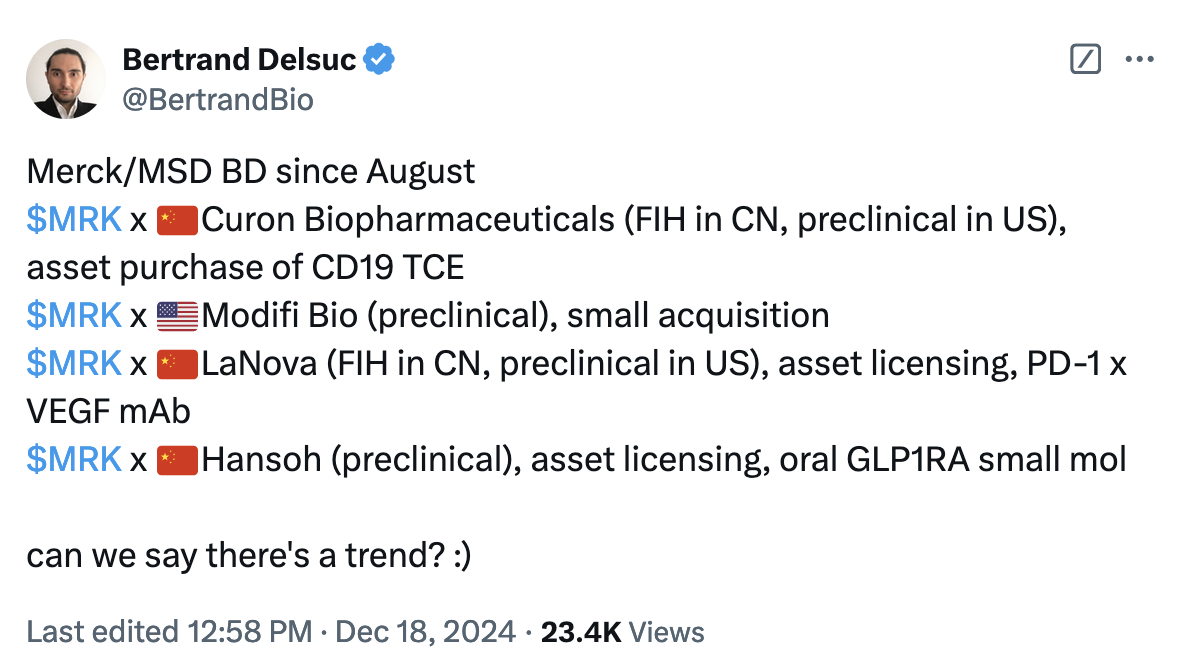

The Legend-J&J deal generated a lot of discussion back when it happened, and perhaps could in retrospect be seen as the canary in the coal mine for the industry. Yet it seems like Merck’s business development activity over the past few months is what is really waking people up to the trend. As Betrand Delsuc posted on Twitter, Merck did four deals since August, three of them with Chinese companies.

In November, Merck licensed a bispecific antibody drug from LaNova in a move that industry commentators see as a response to the somewhat shocking results of a clinical trial reported by US biotech Summit Therapeutics back in June. Summit’s drug ivonescimab, itself licensed by Summit from a Chinese biotech, managed to beat Keytruda (Merck’s $25 billion a year cancer megablockbuster) in a head-to-head clinical trial in lung cancer.

Merck followed up on the LaNova deal a month later with a $112 million dollar deal with Hansoh to get access to an oral GLP-1 drug, which they hope will give them a shot of competing with obesity megablockers Wegovy/Ozempic and Zepbound. This latest deal is especially worrying if you’re an up-and-coming Western obesity biotech, because it increases competition while removing a source of exit liquidity. Every major pharma is looking for a way to get a share of the lucrative yet hypercompetitive GLP-1 obesity market, and like a game of musical chairs, any upstart biotech without a big pharma partner is likely to be left without the necessary resources to take their drug through development and market it effectively.

But why now? What changed to make China such a compelling source of novel drugs?2 From what I can gather, we can trace the change to four main forces: regulatory reforms, returning talent, industrial evolution, and venture funding.

Most people seem to point to 2015 regulatory reforms – part of Beijing’s ‘Made in China 2025’ initiative – as the spark that set off China’s current growth in innovator drug discovery. Under CFDA3 director Jingquan Bi , the agency cleared a massive backlog of generic applications, hired more reviewer staff, and dramatically cut review times for new drug applications from years to months. The impact was immediate – the number of first investigational new drug (IND) applications for innovative drugs jumped 78% in 2017 compared to the previous year. By 2018, China had joined ICH (International Council for Harmonisation), making its drug development system compatible with Western regulators.

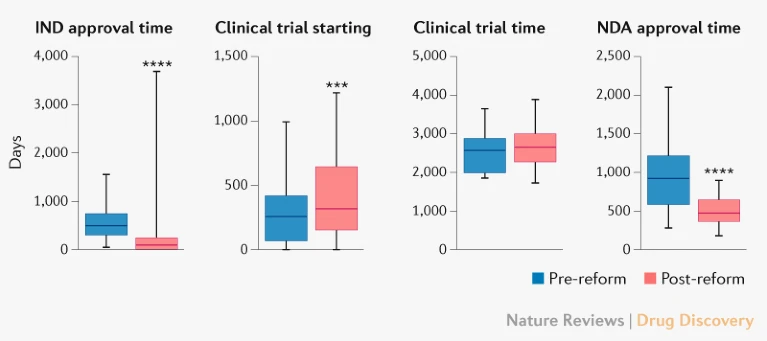

But probably the most important change was slashing clinical trial start-up times, especially for first-in-human (phase I) trials. Before companies can test their drugs in humans, they need to submit an IND application to their country regulator. The Chinese IND process was slow and burdensome, regularly taking over a year for approval. The CFDA shifted to an “implied license” approval system for clinical trials in 2018 — if regulators didn’t raise concerns within 60 days of an IND, companies could proceed. As a result of the reforms, the average time for IND approval dropped from 501 days before the reforms to just 87 days after.

The 2015 reforms coincided with a wave of returning biotech talent (“sea turtles”) who had been trained at top Western universities and companies. They brought with them not just scientific expertise, but also deep understanding of modern drug development. Sports_Bios has an interesting post on Twitter about the cultural factors driving Chinese scientists to return home, including greater opportunities and societal respect. As he puts it:

“many people good at small molecule chem work or protein engineering work - are not ethnically Western - sorry to say - why stay at a Pfizer or [Merck] and be a grunt for years vs going back “home” as many did in past decade”

The sea turtles returned to strengthened industry foundations, thanks to decades of manufacturing experience. China has long been the world’s factory for APIs and generic drugs, which helped them build deep expertise in process development and manufacturing. Contract research organizations (CROs) like WuXi AppTec built sophisticated capabilities while serving multinational clients, creating infrastructure that new biotechs are building off of today. Some CROs even used their service revenue to fund internal drug discovery programs. Chinese discovery labs have matured to rival U.S. facilities in many fields, but with significantly lower operational costs — scientists’ salaries are often a quarter of their Western counterparts.

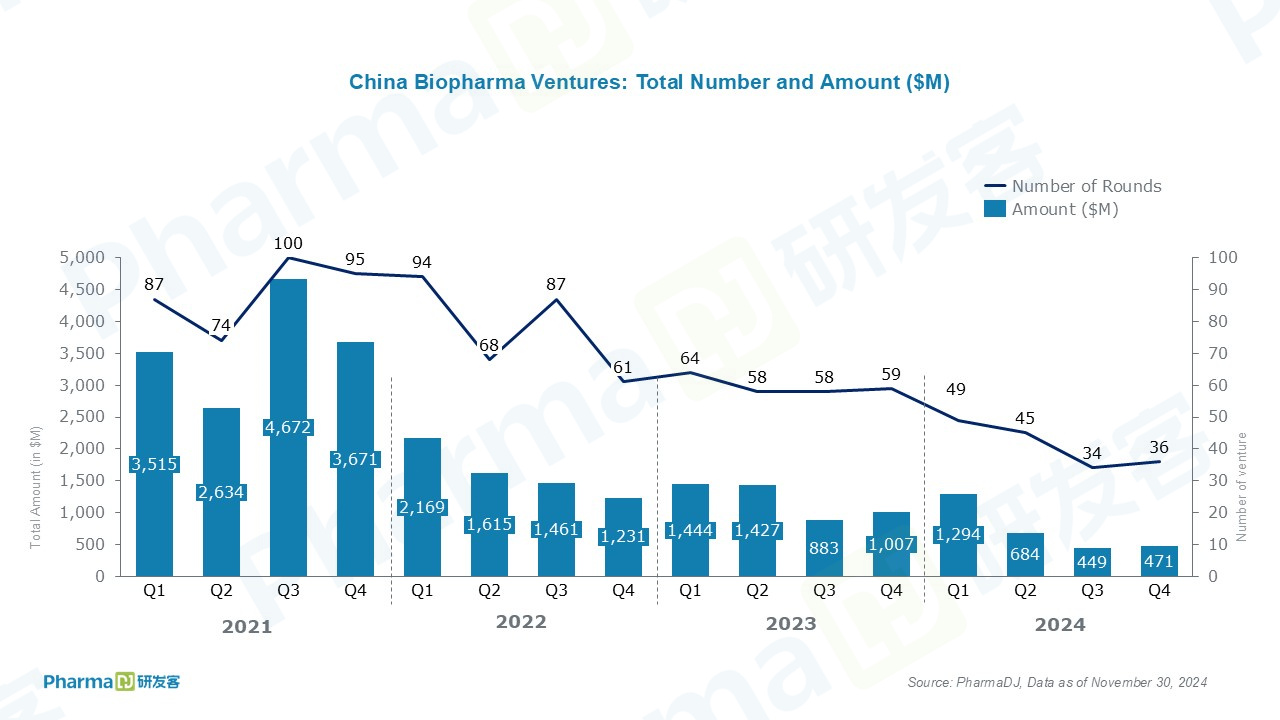

Fueling the growth was a post-reform boom in Chinese venture funding that set off a surge in local company formation. Venture capital investment in Chinese biotech tripled from $4 billion in 2015-2017 to $12 billion in 2018-2020, as McKinsey notes in a report. These factors — returning expertise, a solid industrial base, funding — enabled the Chinese biopharma industry to leap up a rung on the value chain (i.e. the “tech tree”) to occupy a globally competitive position in drug discovery.

If there’s any single factor that matters the most, it’s probably that Chinese companies are just faster. Legend was founded in 2014, got into clinical trials in 2016, and did its deal with J&J in 2017. By contrast, it usually takes Western biotechs 3 to 6 years to satisfy IND requirements and get a new drug into the clinic. Part of the reason why drug programs progress slowly is the extensive derisking that companies do to conserve capital; while Western companies might hesitate to run multiple parallel experiments due to expense, Chinese firms can afford to try many approaches simultaneously. In Sports_Bio’s words:

“they move things quick, they work very long hrs, and they will catch every loophole from a published patent and run thru those - out of the thousands of molecules they play around - they will eventually find some that will work - then the speed of clin testing - the process is way more streamlined there - they can hit with the human data much sooner vs a parallel case in the west”

Western biotechs that discover promising new targets for intractable diseases are finding that Chinese teams take their published ideas and beat them to generating clinical data. Some have noticed the increasingly “sharp elbows” of Chinese researchers scouring posters at Western medical conferences for the latest breakthroughs in recent years.

When I ask people in business development what trend they think is likely to have the largest impact on the industry in the next 5 years they usually say the rise of Chinese innovators (artificial intelligence is usually #2).

A reason to think that China’s rise might not last is the recent fall-off in venture funding. With investor capital drying up, Chinese companies are perhaps more desperate to sell assets for cheap than they might otherwise be, and Western companies are a ready source of money. But, given the other tailwinds, it’s hard to see this as anything but a temporary blip.

At this point it seems almost inevitable that China will become the numerical leader in new drug origination within a decade. If this happens, the big losers are unlikely to be the big Western pharmas (after all, they’re getting good molecules for cheap), but rather the innovator ecosystem of Western startups and clinical-stage biotechs that have traditionally fed the pipelines of the pharma giants. Licensing deals are a major source of revenue that biotechs use to fund operations and research, revenue that is now being redirected to China. The European biotech scene, already fading in relevance (partly due to a weak local market following aggressive pricing constraints), might drop off entirely.

Drug discovery could just be the latest area where China is growing to dominance in a way that echoes the past offshoring of manufacturing. First manufacturing, then automakers, now new drugs. The Western discovery biotechs of today may look increasingly like the Western machine shops of the 1980s.

I’d be disappointed if the policy response was to enact wasteful subsidies or block deals with China4. Rather, as I, and others, have argued policymakers should make it easier and cheaper to run clinical trials. Progress in biopharma is ultimately driven by a fast feedback loop of human data collection. China’s regulatory reforms have made it faster and cheaper to get drugs into humans, and the learning rate of the Chinese biopharma ecosystem seems a lot higher at the moment than the US or European ones.

Returning briefly to the auto industry again, we can see one possible future for our industy in how Western governments are responding to the threat Chinese EVs pose to domestic automakers.

Following concerns over Chinese EV subsidies and industrial policy, the Biden administration placed 100% tariffs on Chinese EVs that came into effect in September this year. Europe responded similarly in October, implementing tariffs of up to 45%. As justification for their decision to implement tariffs, the European Commission cited the increase in Chinese EV market share from 3.9% in 2020 to 25% in September 2023. Speaking about the tariffs, Biden said:

“I’m determined that the future of electric vehicles will be made in America, by union workers. Period.”

Policy responses aside, I can conceive of two potential paths for Western innovator discovery biotechs to remain competive in the face of ascendent Chinese competition.

The first is to focus on the kind of novel frontier research where Western scientists and universities still have an edge (for now). This probably looks like a combination of partnerships with top university departments, licensing unique patient datasets, and building edge-science (almost fringe) platforms — going after moonshots with the potential for step-change improvements in efficacy or safety, in other words. For any me-too opportunity or validated target accessible to standard drug modalities there are likely to be 10 or more Chinese companies pursuing it more quickly and cost-effectively than a Western biotech can, so it’s almost pointless to try and compete with a weakly differentiated asset.

The second is to embrace technology and automation as a means to hyperscale lean teams: cloud labs, automated lab-in-the loop machine learning, AI researchers, language model document generation, etc. Chinese biotechs scale better with labor costs; the way to compete against teams that are 75% cheaper is to make each of your employees at least 4x as effective.

Of the two possible future worlds, one where policymakers respond by locking down Western-Chinese collaboration and one where Western discovery biotechs stay relevant by becoming much more capable, I hope it’s the latter future that comes to pass.

-

I thought my cofounder Vikas’s feedback on this point was interesting and worth including, at least as a footnote: “EVs have been a core catalyst for Chinese automotive companies to leap ahead of the Europe-Japan-US hegemony in many respects (cost efficiency, in vehicle experience, autonomous driving features). German automakers built beautiful engines, Japanese automakers were reliable, Americans built power but all of those advantages are irrelevant with the move from ICE to electric engines. I’m curious if there’s any interesting analogy in pharma.” ↩

-

If you want to read an in-depth historical treatment on this I recommend this Endpoints article from 2021 titled “How China turned the tables on biopharma’s global dealmaking”. ↩

-

The Chinese version of the FDA ↩

-

Although it’s stalled for now, that the BIOSECURE act came close to becoming law suggests there is plenty of legislator appetite to curtail US-China biotech relations ↩