Latent optima

All data is the result of some selection process. The first order manifestation of this is bias: a failure to select a representative sample of the real underlying thing the data is describing. But selection operates at multiple hierarchies. For something to exist such that data can be collected about it, that something must have been created instead of some other thing — it must have survived a selection process. Because of this, any dataset includes latent information about the traits that tend to survive these selection processes.

For example, if you counted up all the members of every species on Earth the resulting dataset would give you some information on the types of creatures that tend to do well in Earth’s biosphere. If you then counted how many of those creatures had fins, and how many had wings, you could get partway towards an understanding of how to construct an optimal ‘model’ animal. A mix-and-match book made real.

Zooming down to a lower level, Karl Friston (and others) have argued that organisms are embodied statistical models of the states of their environment1. This is a way of thinking about an organism as “a hypothesis of its environment”; in the words of Peter Munz:

“The behavior of a fish and the functioning of a theory of water are exactly identical. The fish represents water by its structure and its functioning. Both features define an initial condition (for example, the degree of viscosity of water) which, when spotted or sensed, trigger off a prognosis or behavioral response which, in case of a fish, fails to be falsified. By contrast, a bird does not represent water”

In other words, the states that organisms are most likely to be in are the ones they are likely to prefer2. You find organisms where they choose to be. This may just seem like another spin on the familiar process of evolution by natural selection. But I think the selection-eye-view reveals some deeper truth about what is learned by models when they’re trained on real-world datasets. Machine learning models which learn compressed representations of data also naturally end up learning something about the optimal properties of (and selection process acting on) what they are modelling — even if they aren’t provided information about those properties from the outset.

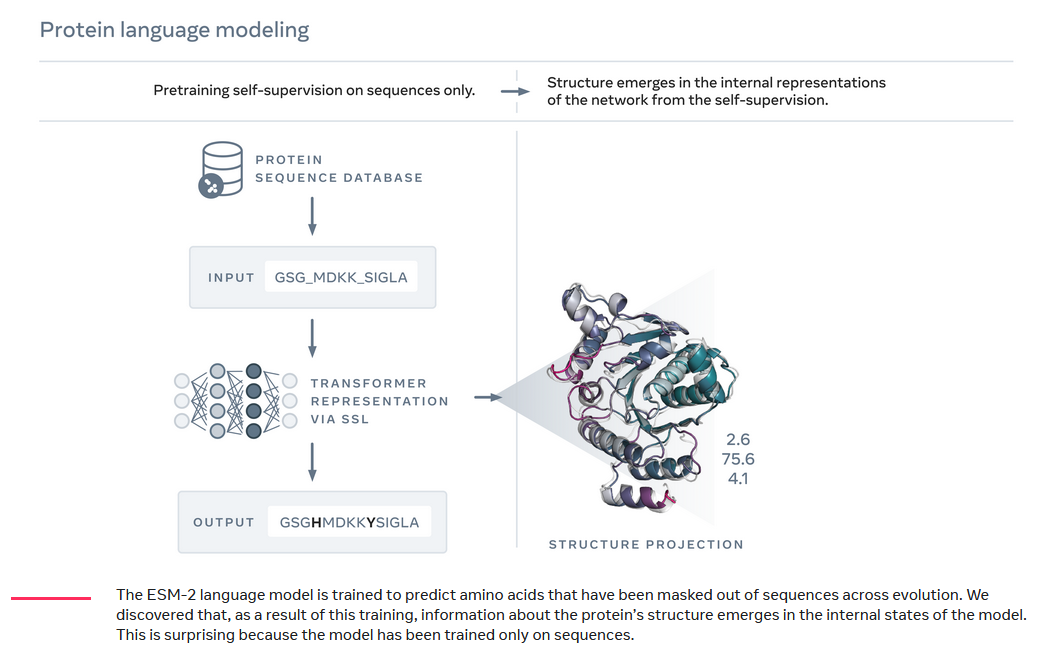

Meta’s protein folding model ESMfold illustrates this principle. ESMfold achieved state-of-the-art accuracy on protein structure prediction, even though its language model was trained on protein sequence data alone: the training process involved feeding the model protein sequences with gaps in them, and getting the model to predict amino acids to ‘fill in the blanks’3.

Nevertheless, the information about the shape of protein folds was latent in the sequence data. In order to learn better and better predictions to fill the missing amino acids, ESMfold’s language model had to create an internal representation of the structure of the protein and how it folded. This internal language model representation could then be read out by a folding module (which was trained on sequence data) to generate accurate 3D protein structure predictions.

Protein folding is a non-random process, and there are ‘best practices’ in how to structure a given protein sequence to achieve a desired structural motif. Evolution has learned these optima and uses them repeatedly, and because they appear frequently, they can be learned. More generally, the set of proteins that exist in the dataset were only able to be sequenced in the first place because they are evolutionary successful. So there is also latent information about the types of sequences and structures that are biologically optimal in the protein sequence dataset.

This principle of latent optimality was exploited by researchers who used Meta’s ESM protein models to improve the properties of monoclonal antibodies that were already highly optimised4. The researchers took antibodies already in clinical use — like Regeneron’s COVID antibody — and ran their sequences through the ESM model, tasking the model with predicting where the true amino acid sequence of the antibodies differed most from the model’s predictions. Then, the researchers selectively replaced the amino acids at those divergent sites with the model’s predictions. These substitutions markedly improved the binding affinity, thermostability, and in vitro potency of the antibodies, without a noticeable increase in off-target binding — all without feeding ESM any information but the protein sequence.

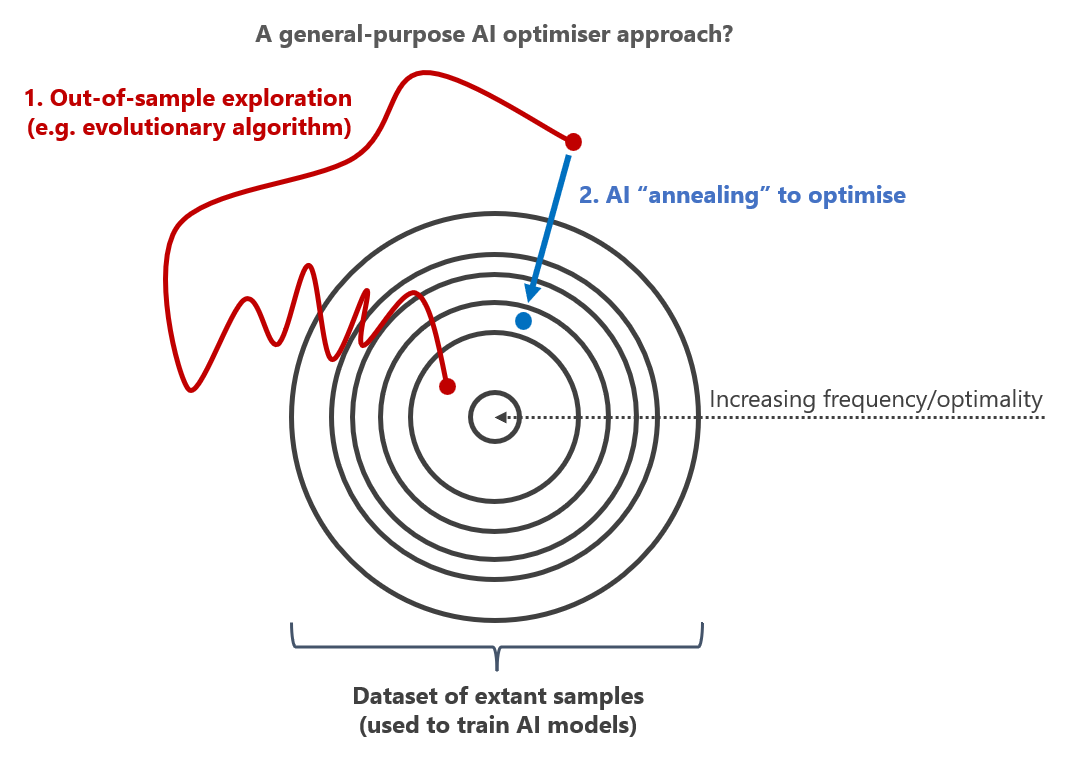

This suggests that because samples in datasets have themselves undergone a selection process, as long as we are confident that the selection process is producing outcomes we care about (which we can be reasonably certain of in biology), we can use the statistical properties of those datasets as a sort of optimisation function in themselves. Exploration followed by AI-informed selective regression, or annealing, may be a valuable general approach to optimise new designs generally5.

One of the challenges of applying machine learning in medicine has historically been that it’s not clear what optimisation function to use. I’ve previously argued that a way around that may be to collect all sorts of data on parameters of biological systems — a detailed description of states — and then use that as an objective function. The evidence from the antibody optimisation experiments using ESM are perhaps a small piece of support in favour of that approach. Biological systems have already undergone billions of years of selection and optimisation — we may as well make use of that latent information.

Thanks to Adam Green and David Yang for giving me the idea for this post

-

I wrote about this at length in my post “Intelligence as efficient model building” ↩

-

Homeostasis is a manifestation of this drive to return to optimal states ↩

-

Jeffrey Chan pointed out that to me on Twitter that I had originally neglected to mention that while the language model portion of ESMfold doesn’t use structure data, ESMfold’s “folding head” is trained on structure data including PDB and 12 million AlphaFold2 predicted structures. The folding head is fed sequence data and the ESM language model’s internal representations of the protein structure as input and outputs the structural predictions (3D coordinates) ↩

-

I wrote about a similar approach in this essay about automating scientific discovery ↩